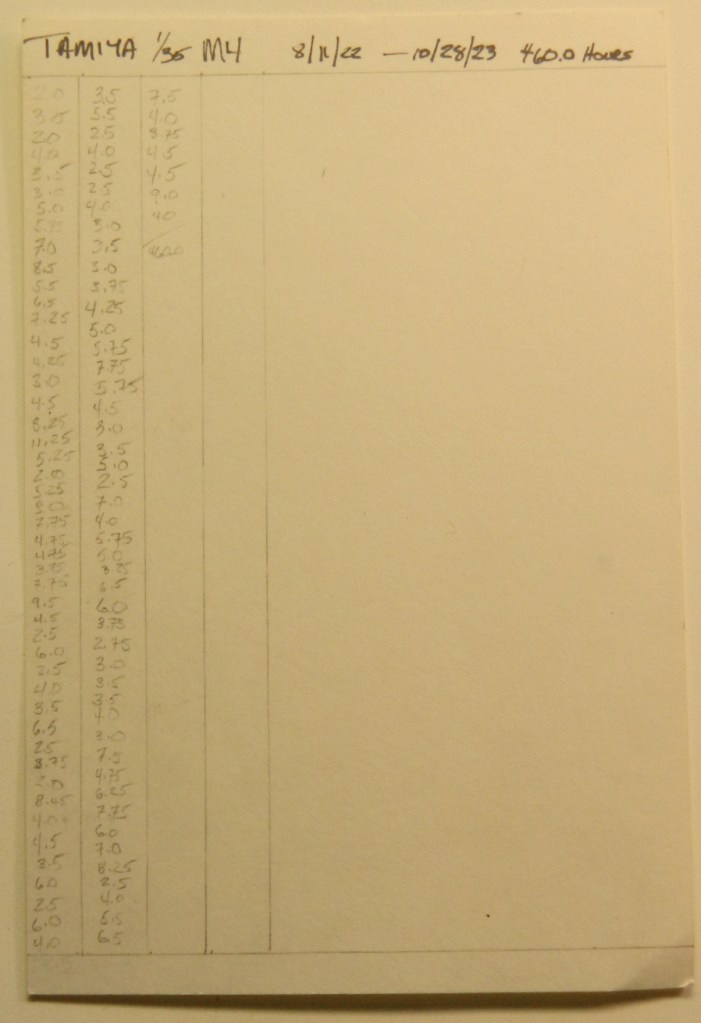

F7F-3 (AMT/Italeri) 1/48 Scale Build #4 –Engines Get Painted, the Landing Gear Bays and Landing Gear are Pre-shaded, and the Landing Gear is Installed

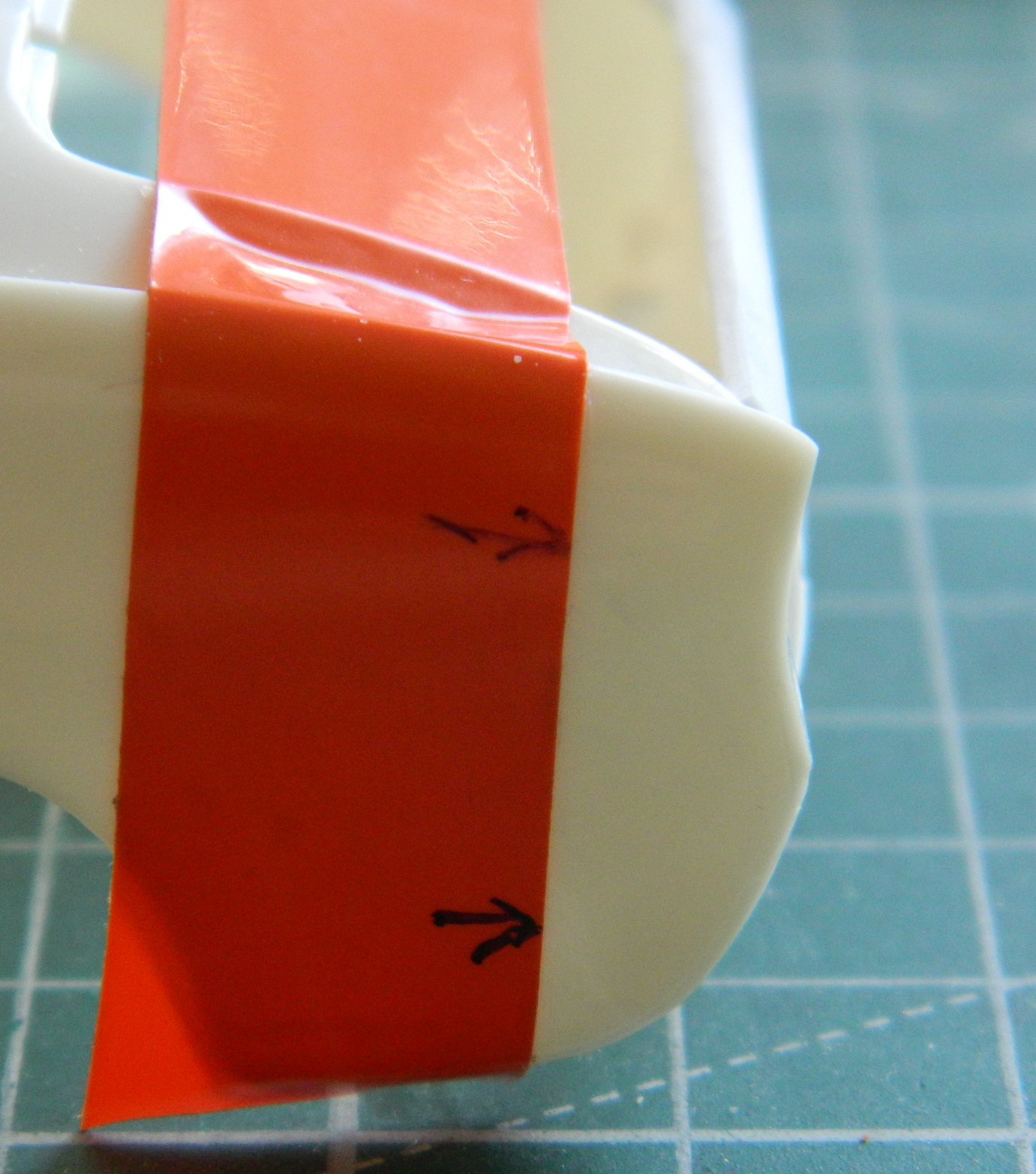

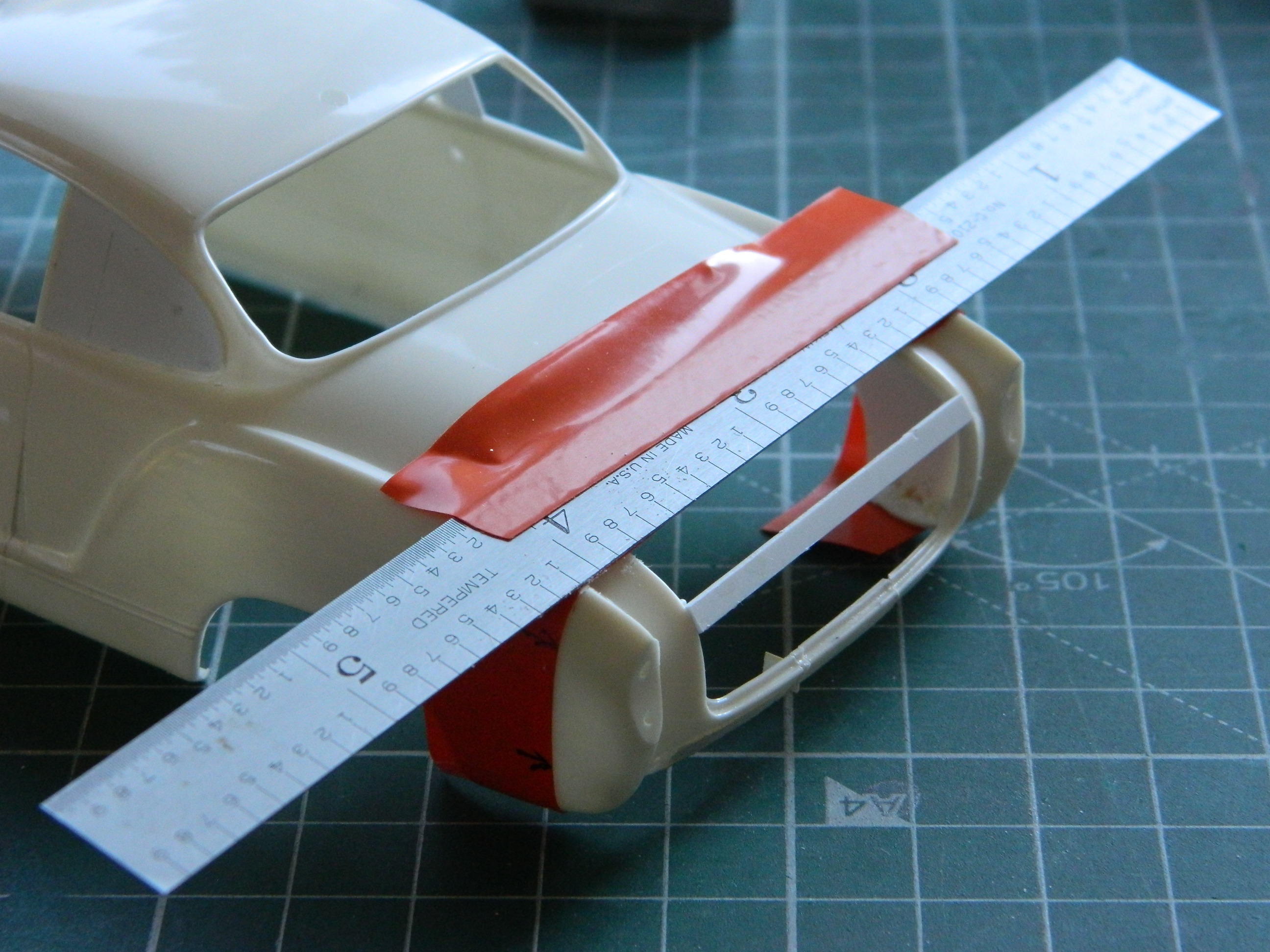

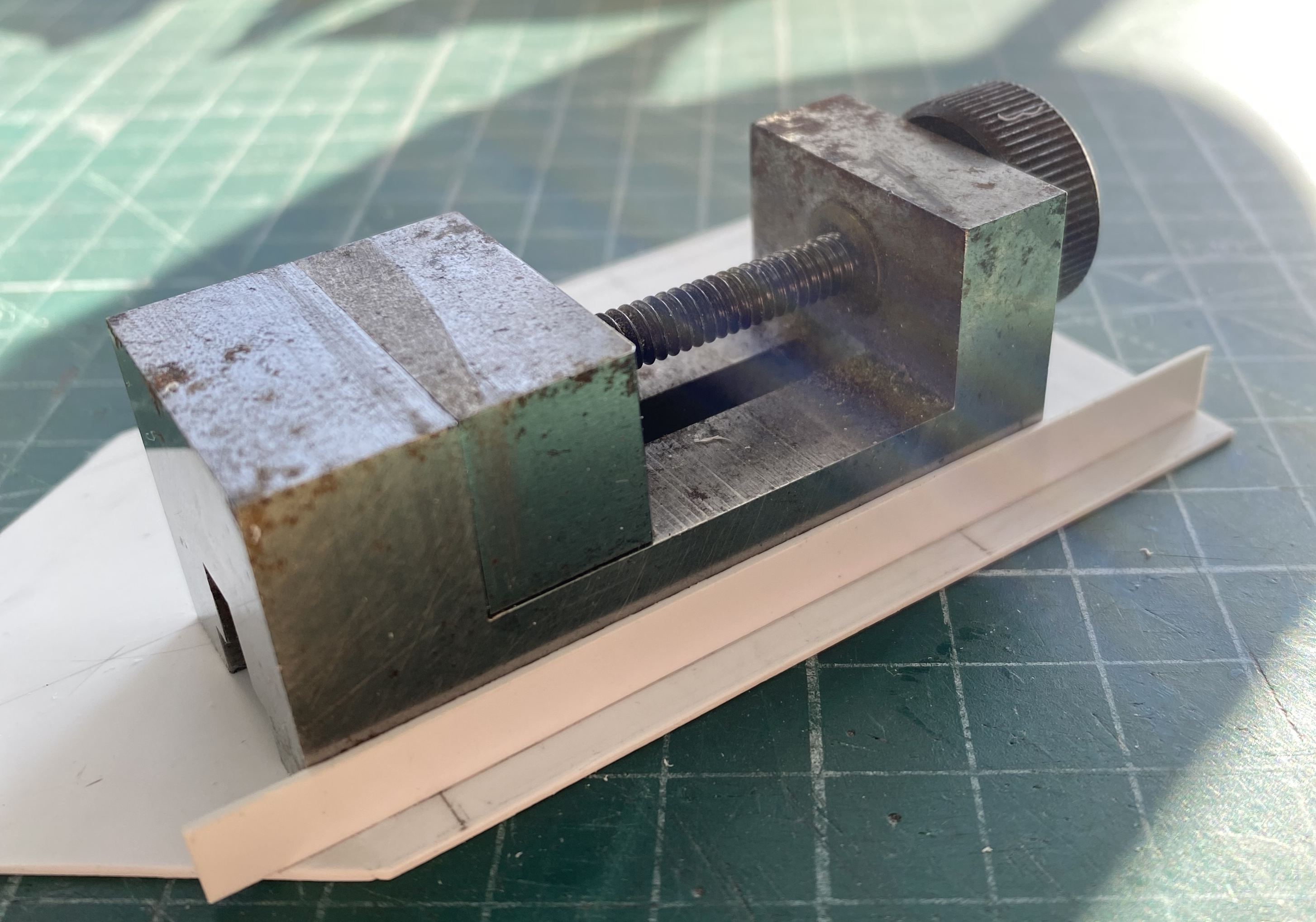

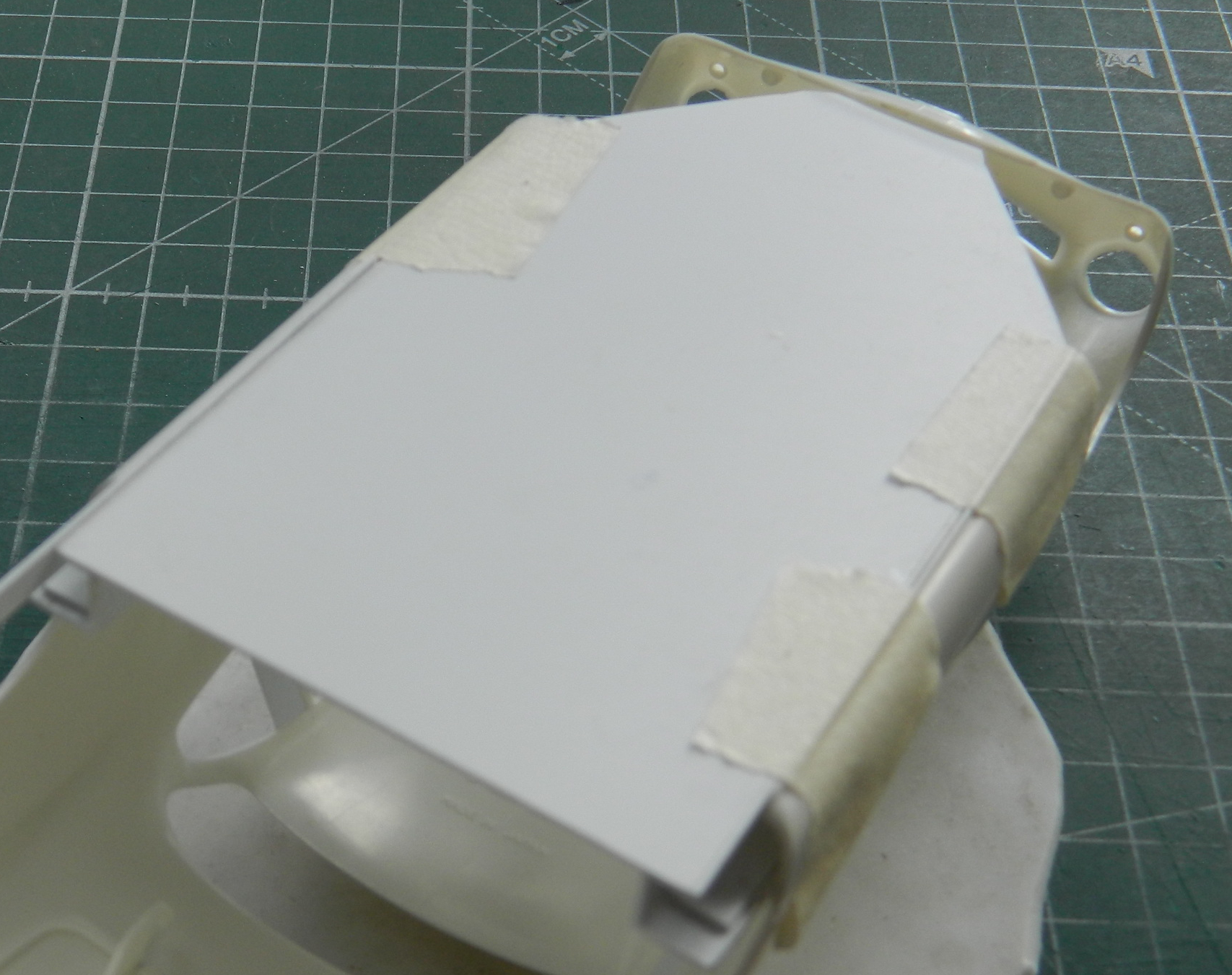

I started this month by asking (and getting an answer) to the question that has been obvious to me. Will this thing sit on its landing gear or will I be another modeler who needs to use something under the tail to keep it off the table. By this point, I’ve stuffed lead and tungsten into any space they’ll fit, so I taped all the major components together to see if I’m even close. I placed the taped-together parts on my fuselage stand with the horizontal supports in touch with the model in line with where the landing gear struts mount:

Yes! It will indeed sit on all three of its tires, though the balance as the nose tire resting ever so gently on the surface. And this is done with zero weight in the nose (not much space but lead will obey the hammer and can be coerced into the shape I need), so since I will be adding more weight to the nose and the forward section of the drop tank (because it extends forward of where the main tires touch the surface). I don’t want an errant breeze having this thing squat like a dog having a slash.

Hammer time:

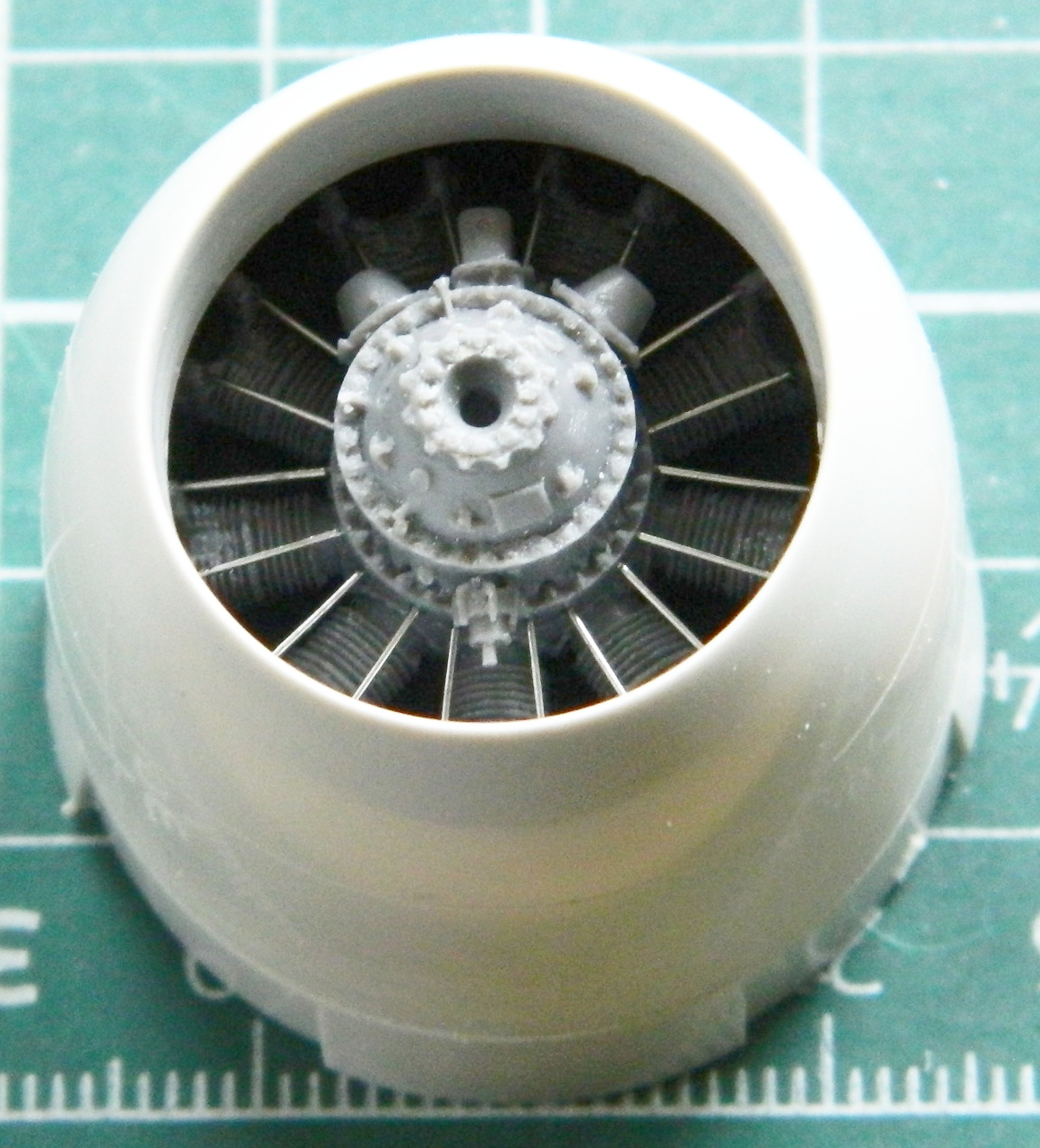

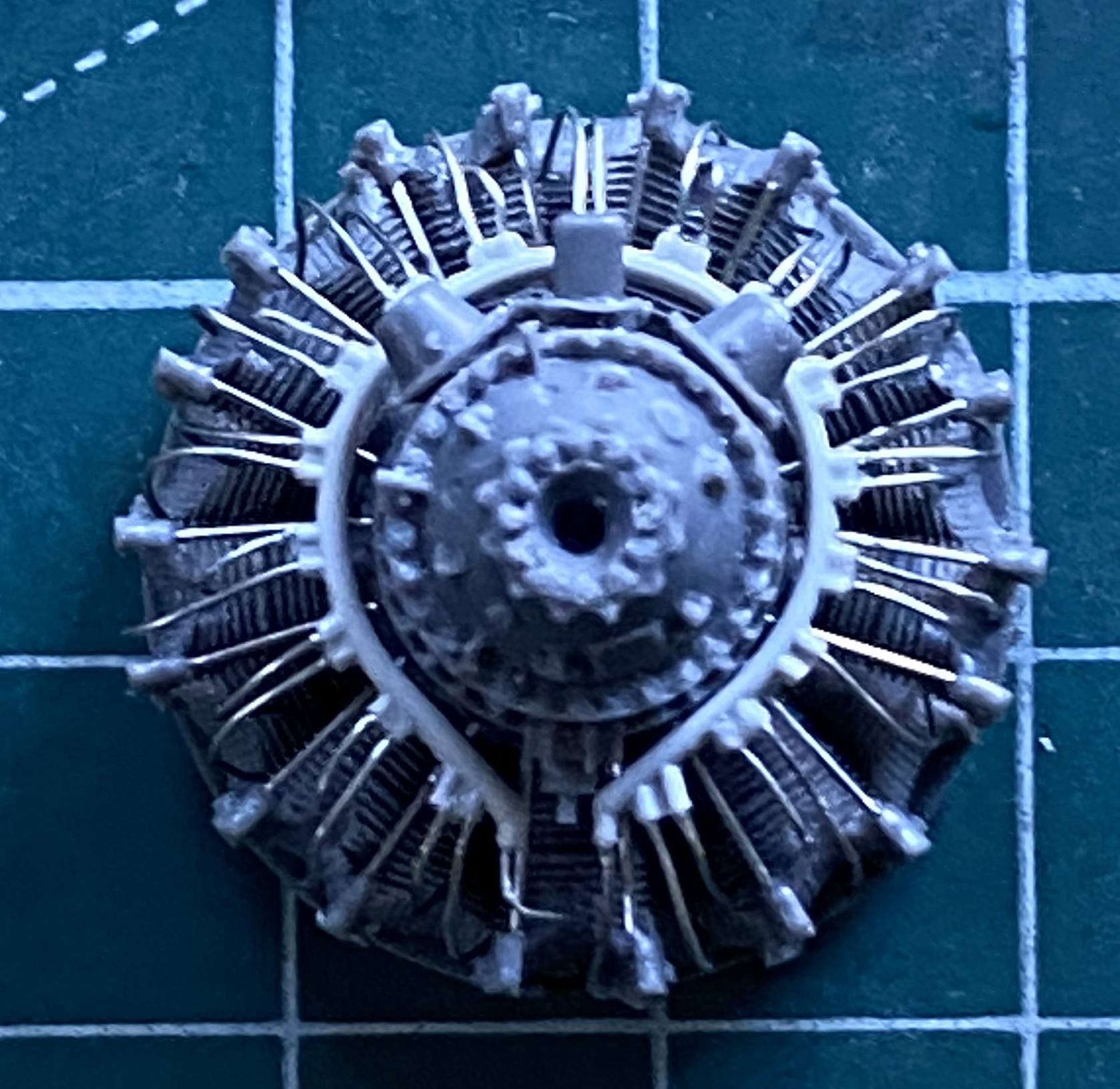

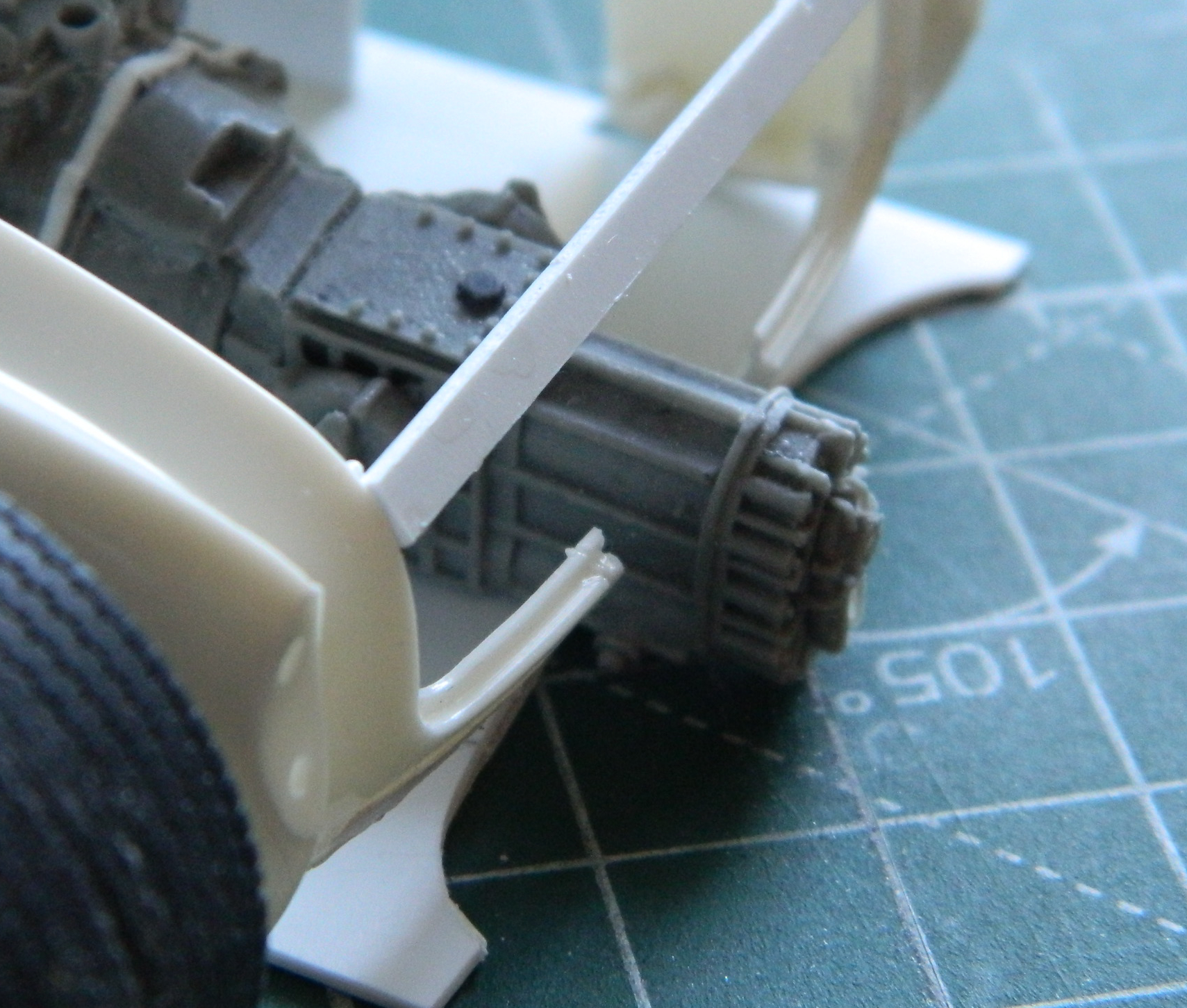

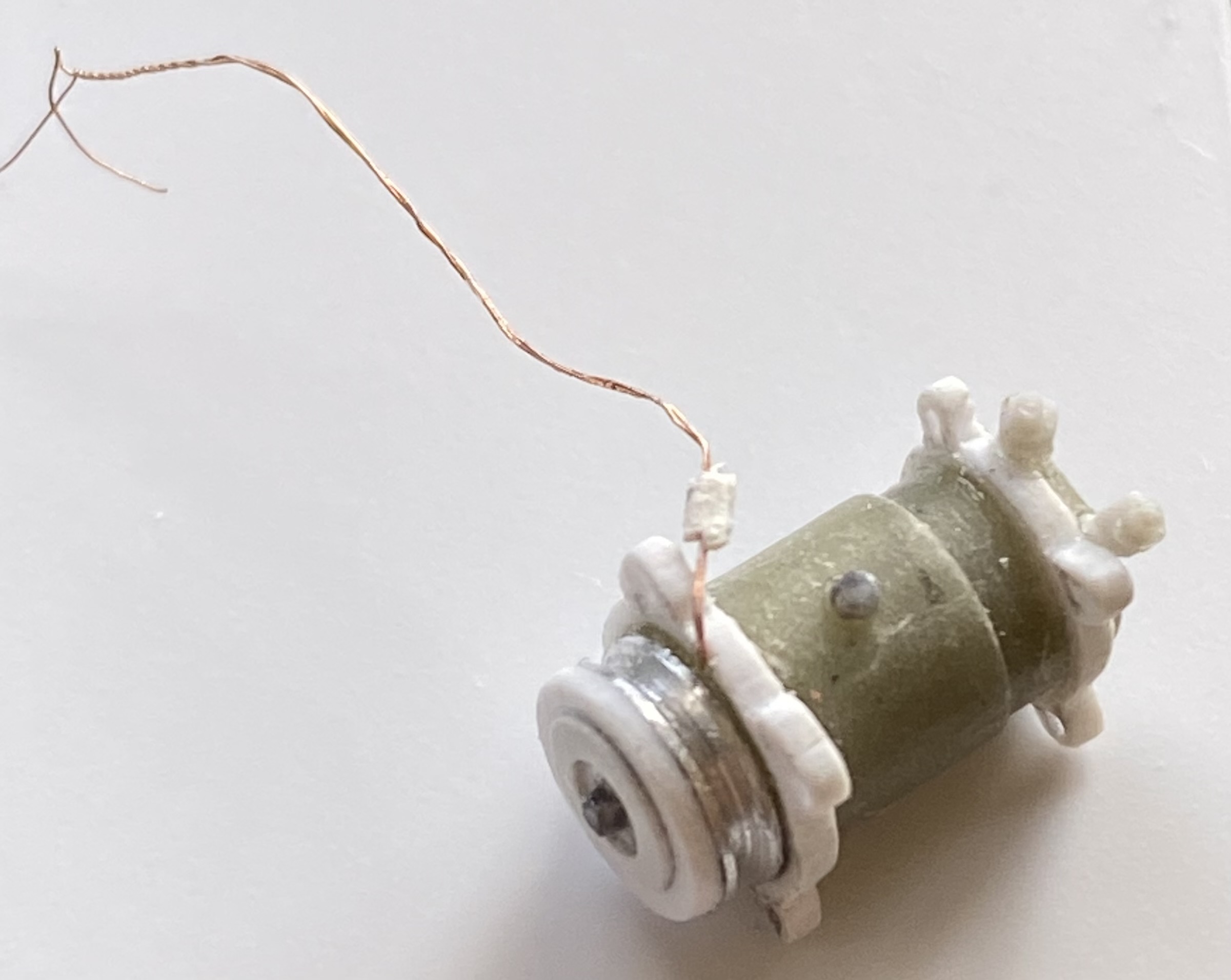

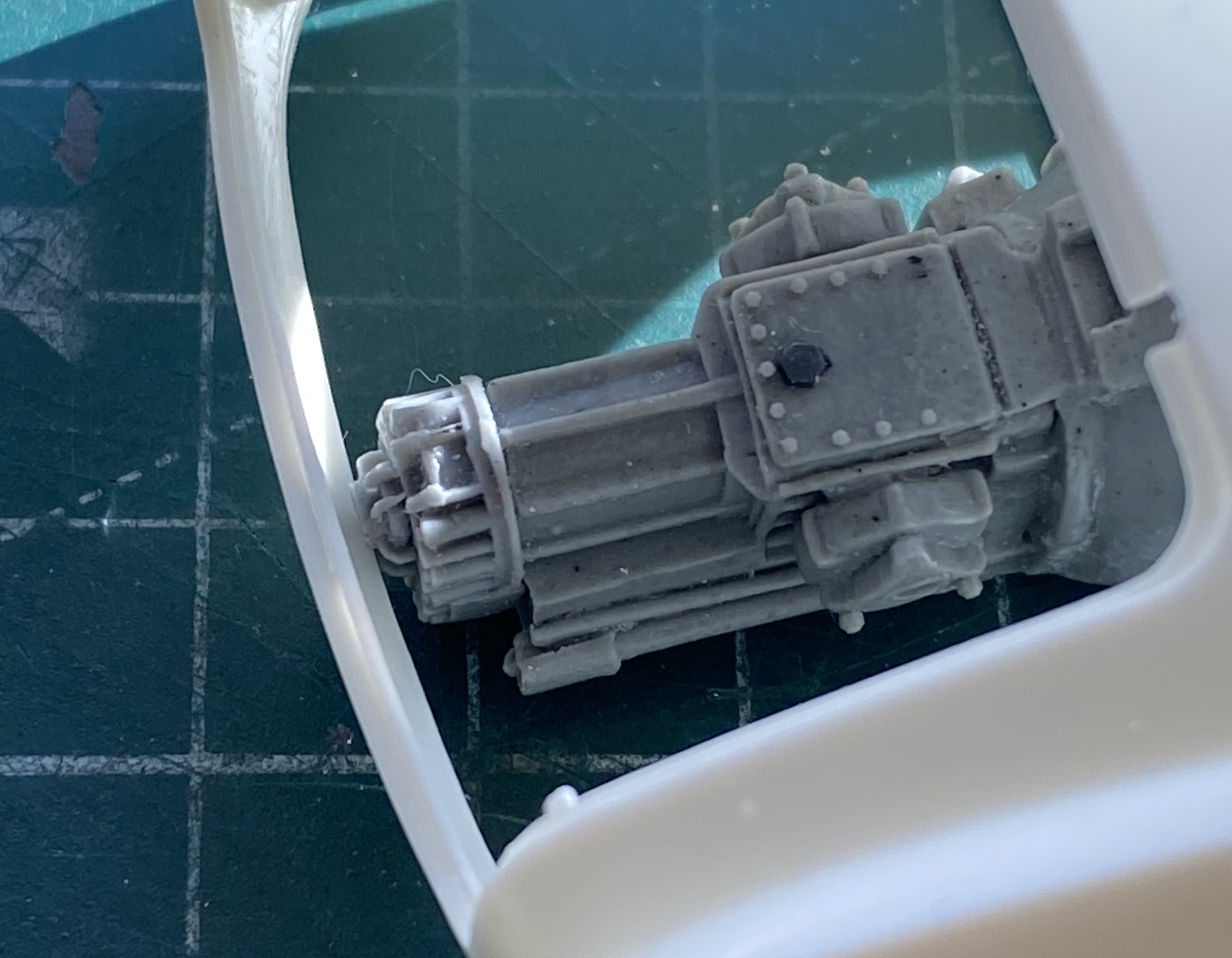

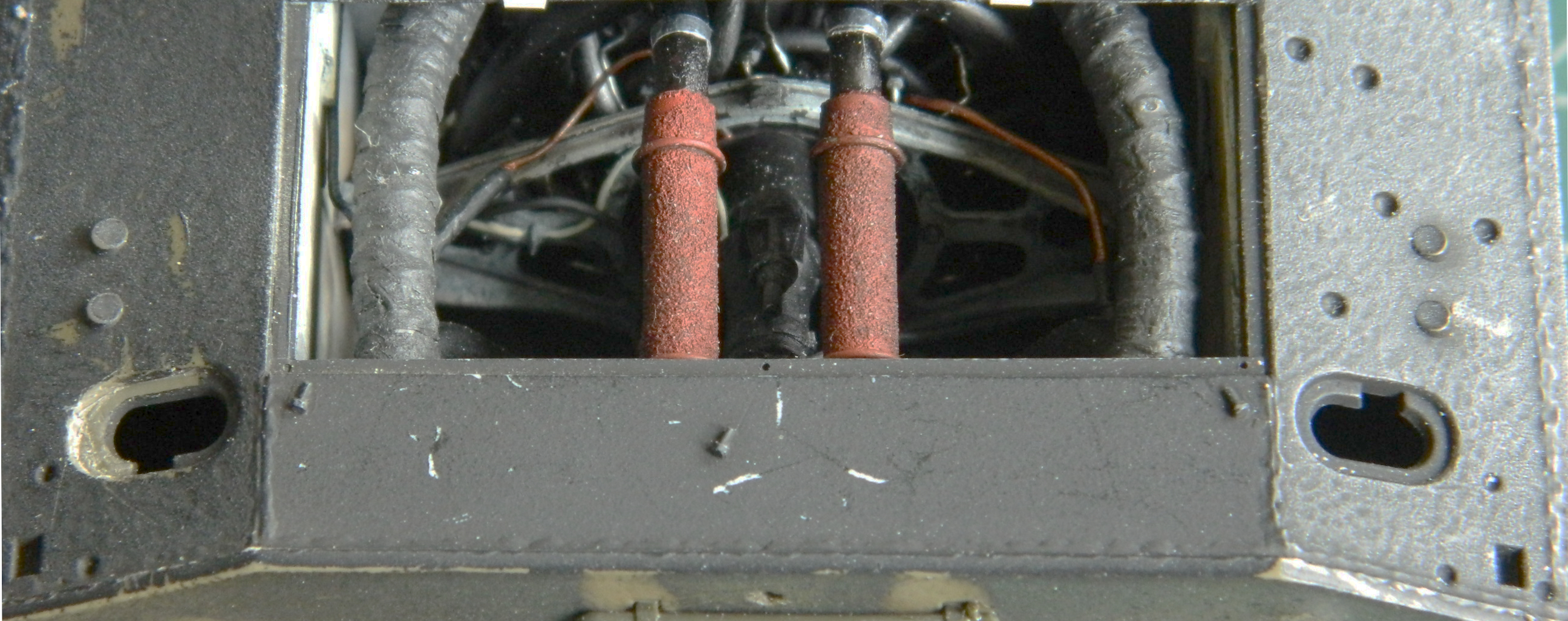

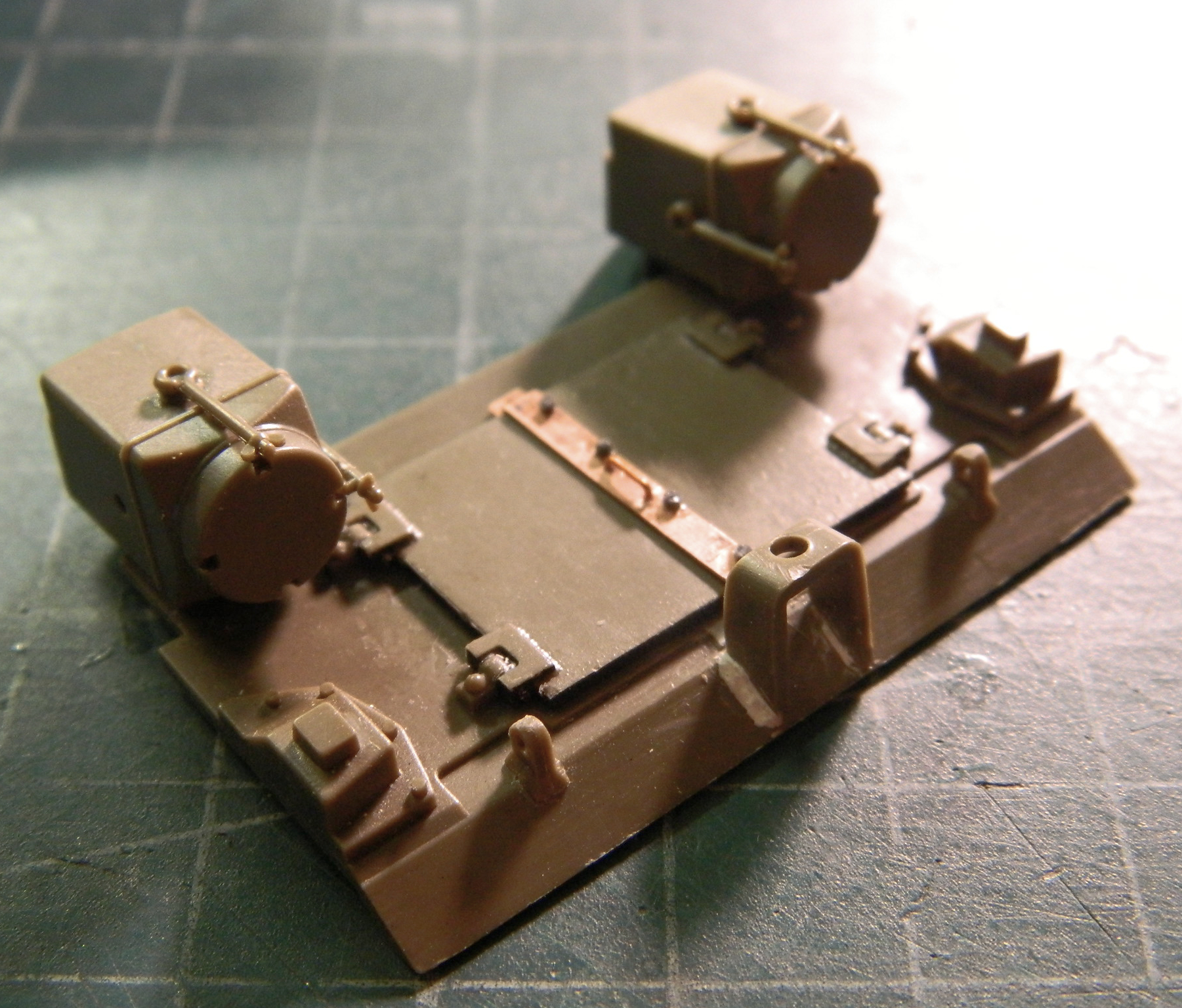

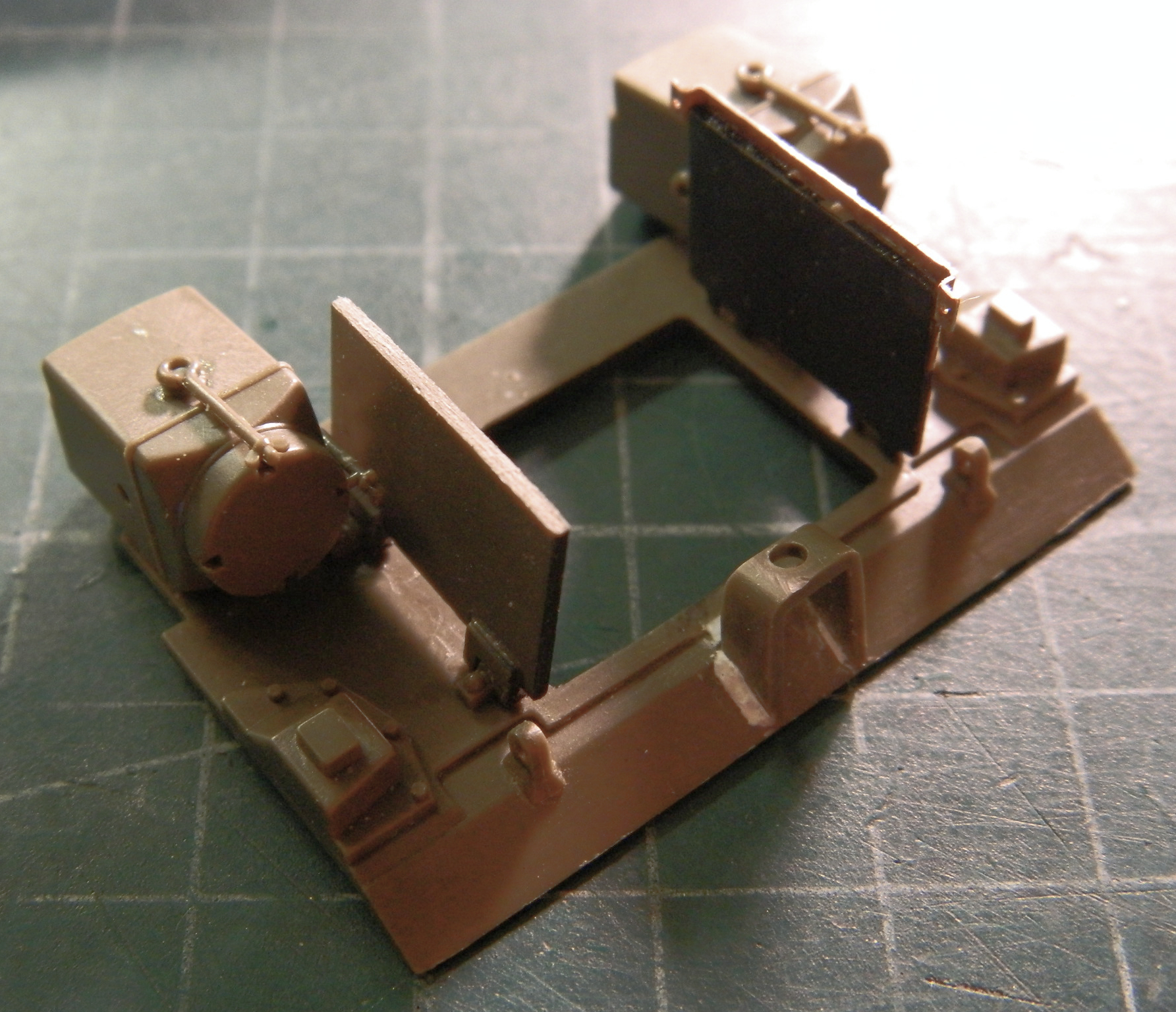

With the Big Question answered, hammer time segued into airbrush time. The engines were pre-shaded with Tamiya XF-1 Flat Black. The crankcase and its bits were brush-painted Tamiya XF-53 Neutral Grey, the ignition tube surrounding the crankcase was painted a mixture of Tamiya XF-6 Copper (two parts) and XF-1 Flat Black (one part), and the wires were done with a mix of Tamiya XF-57 Buff (three parts), and XF-10 Flat Brown (one part). The front of the rocker arm covers were lightly dry-brushed with Tamiya XF-16 Flat Aluminum. The cooling fins were lightly touched with a silver pencil. Then I took a round toothpick with a chisel tip cut onto it to scrape the flat black off the pushrod shrouds:

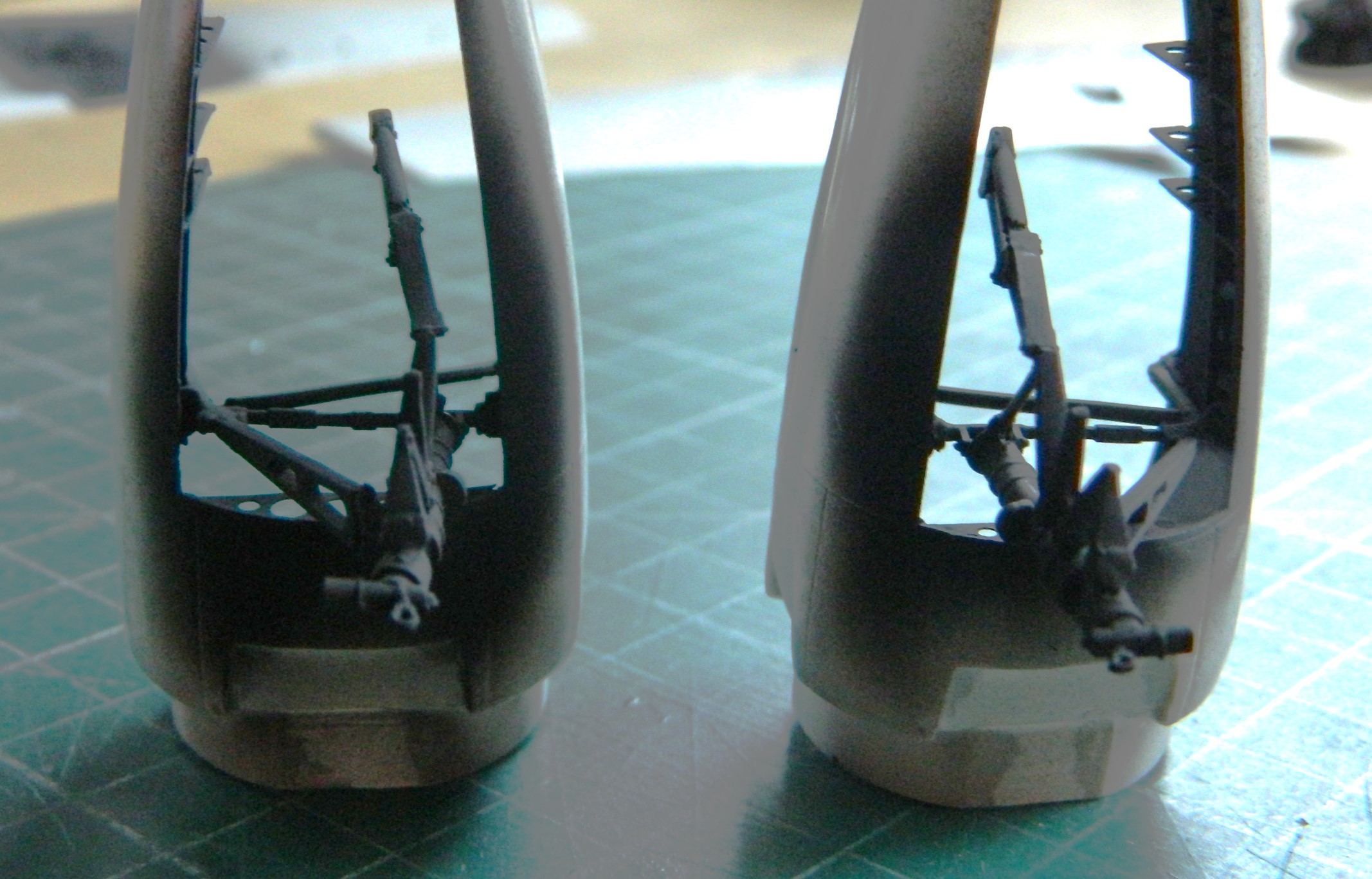

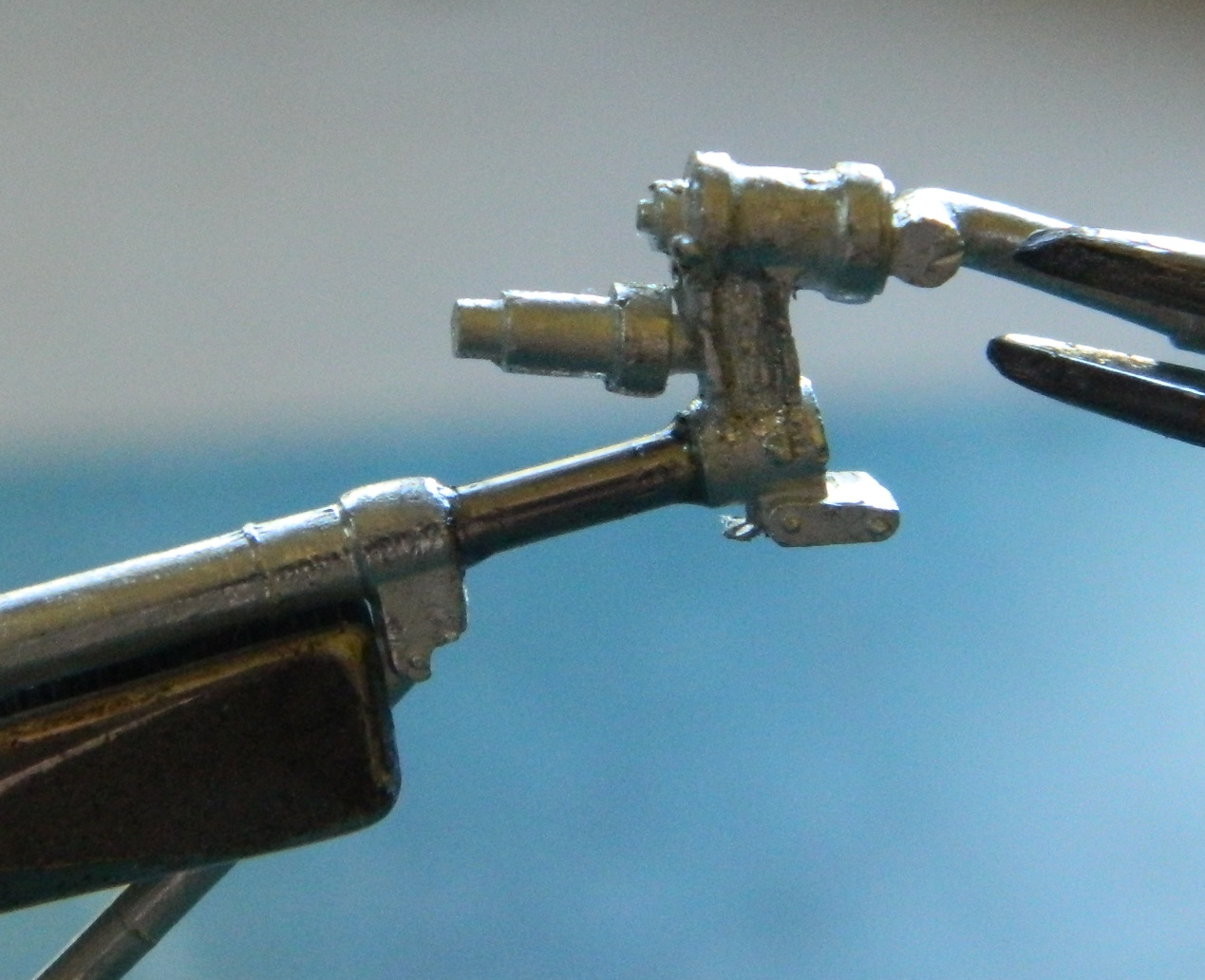

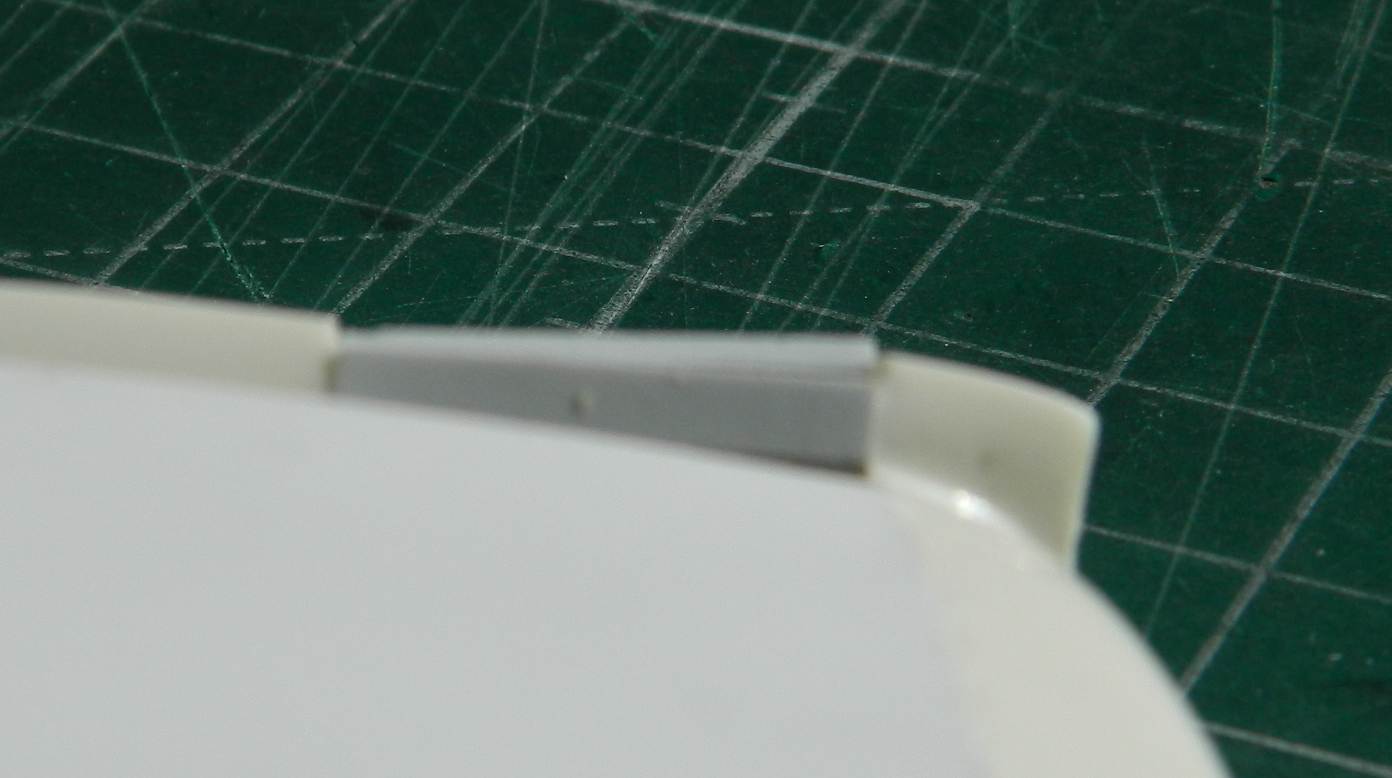

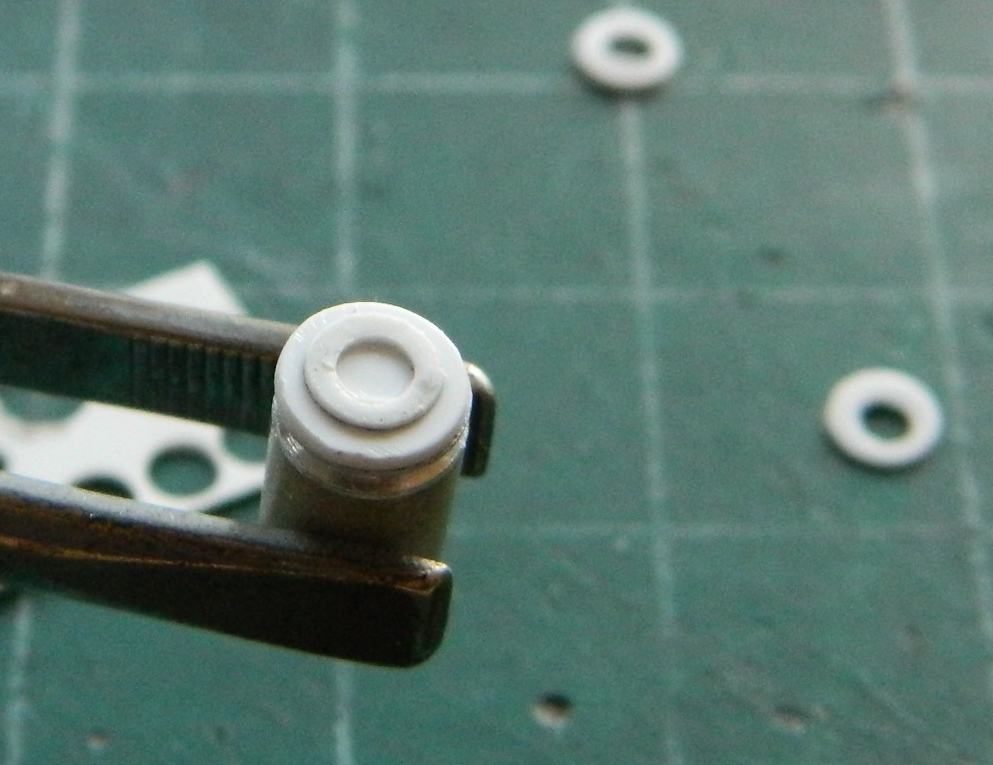

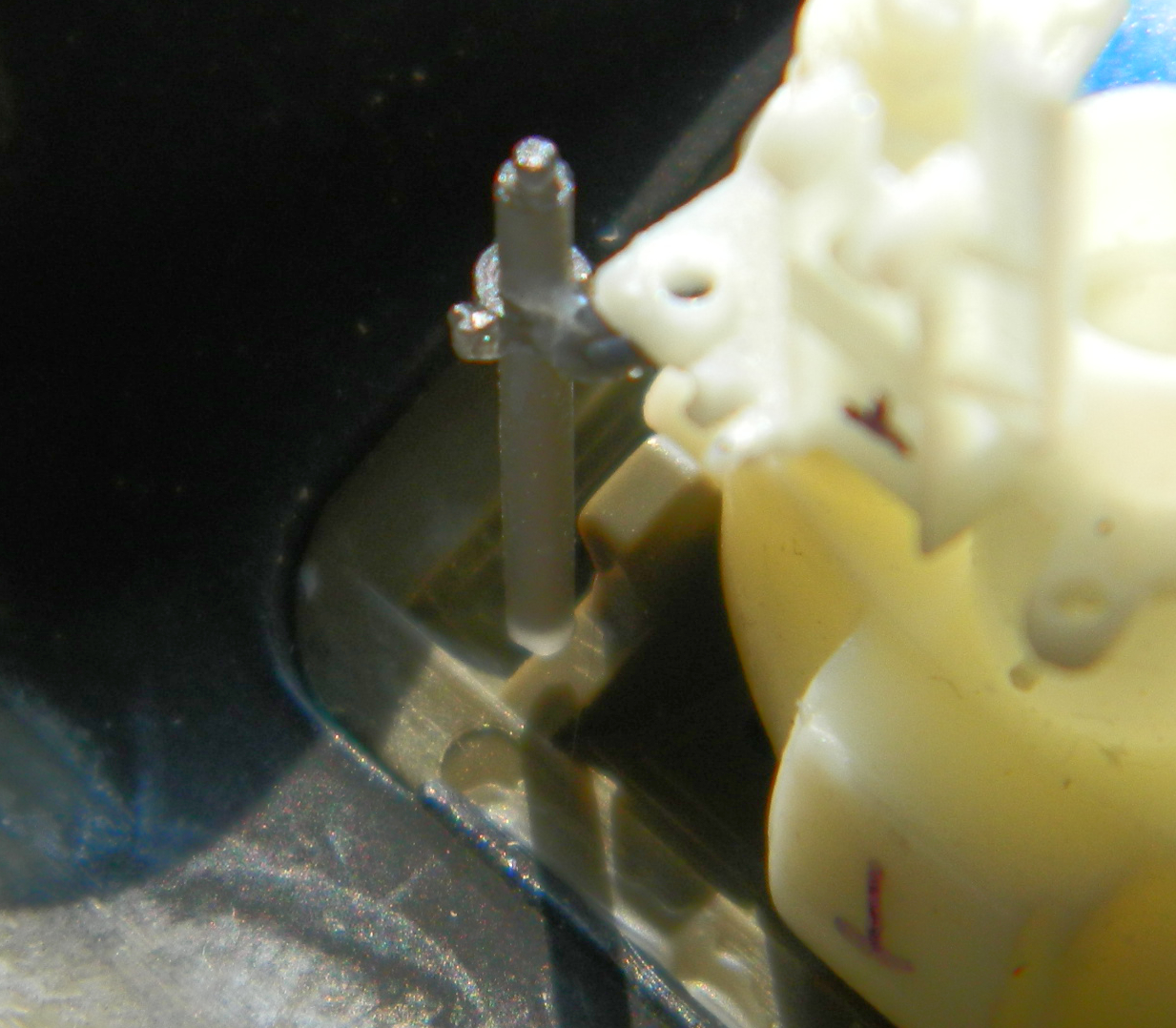

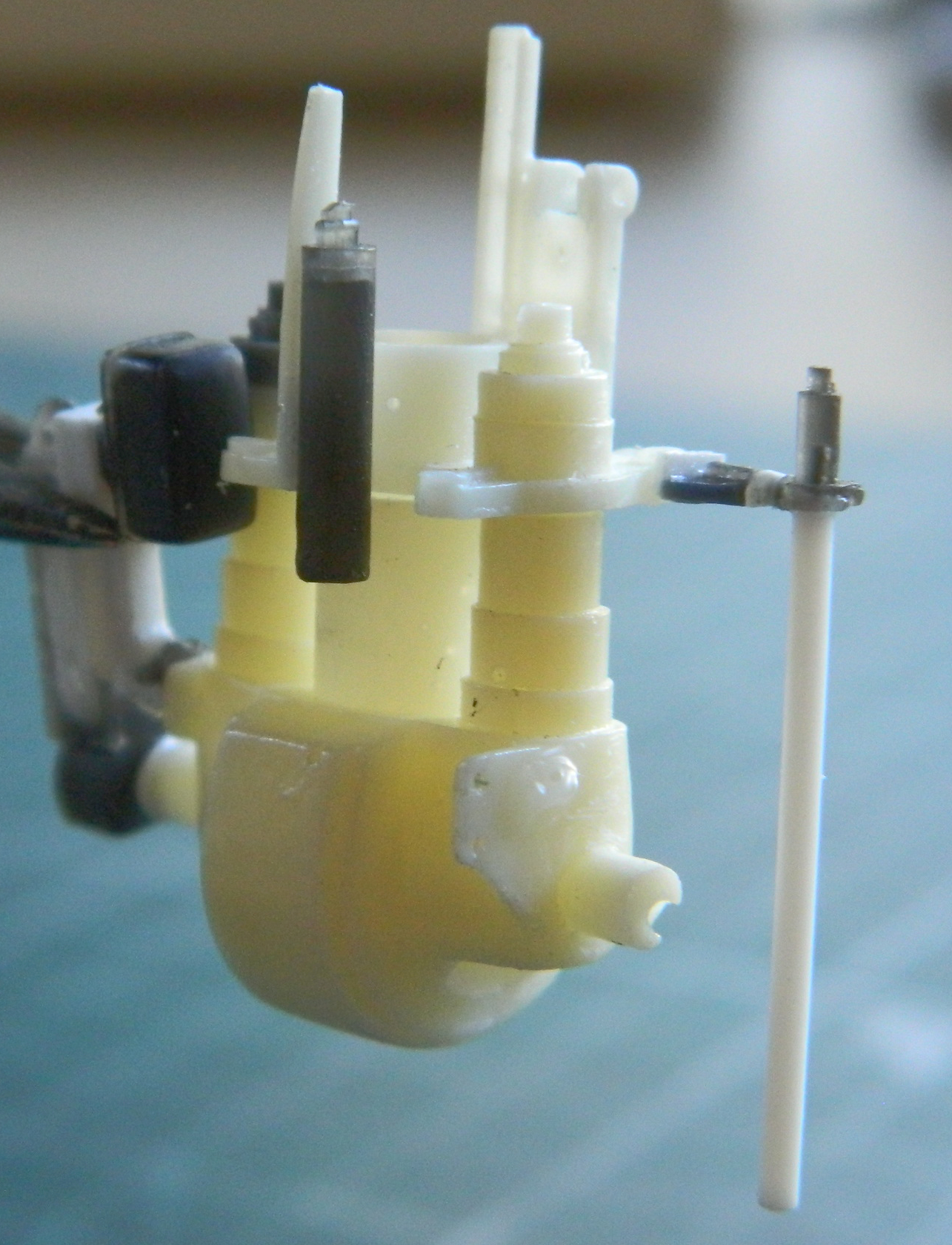

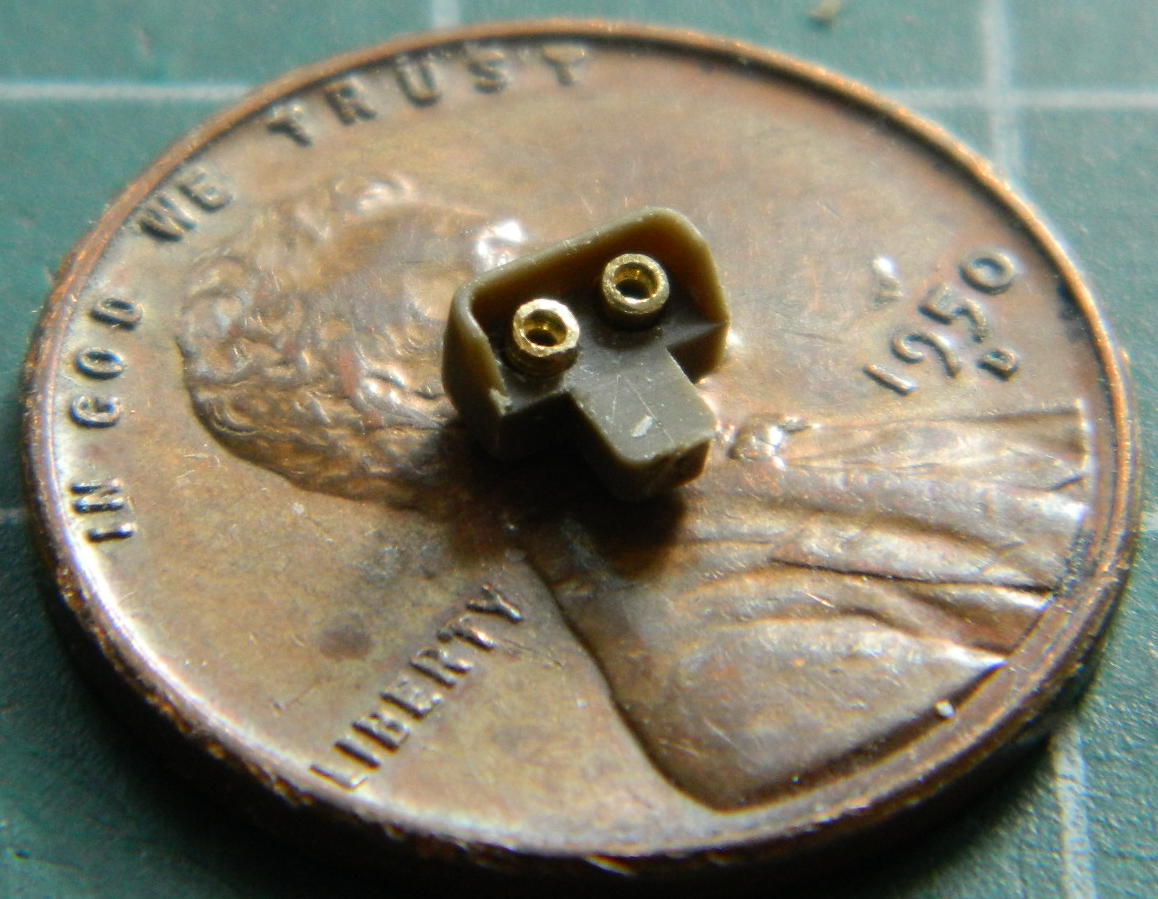

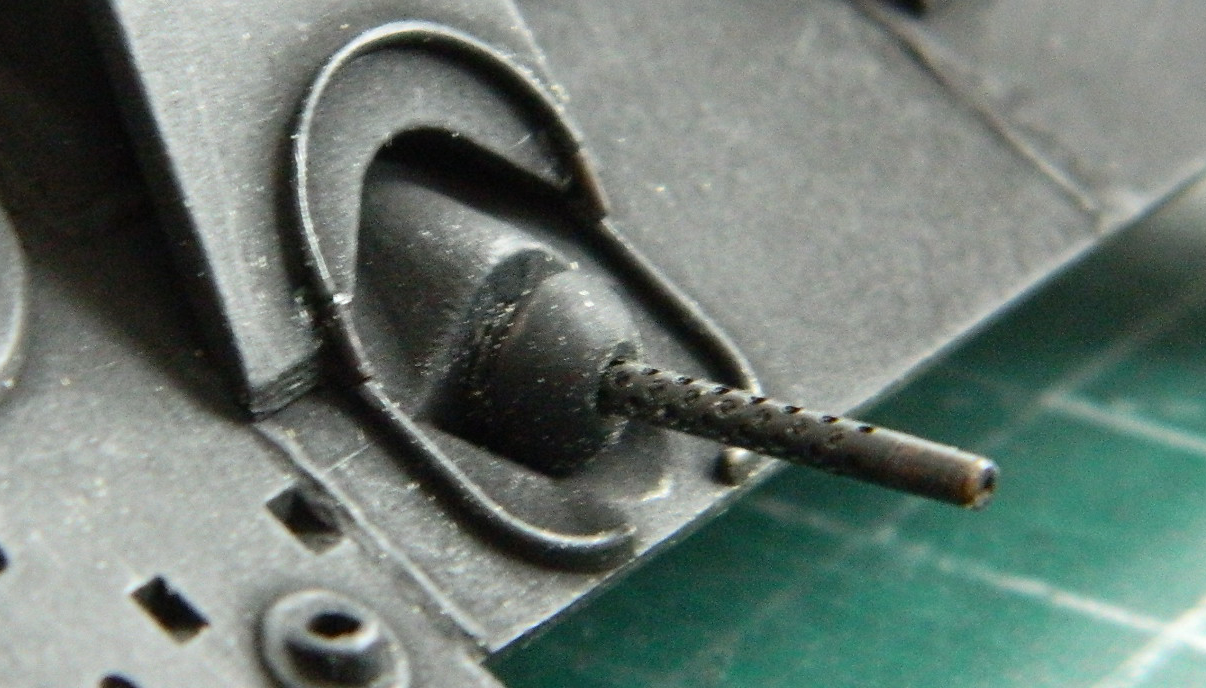

The kit’s pins to mount the propellers didn’t come close to fitting the engines, so I drilled the engines out to accept sections of 0.062″ (1.57mm) instead. (Pain in the thing I’m sitting on that isn’t a chair getting them perpendicular to the crankcases!):

Not a lot showing but that’s as it’s supposed to be.

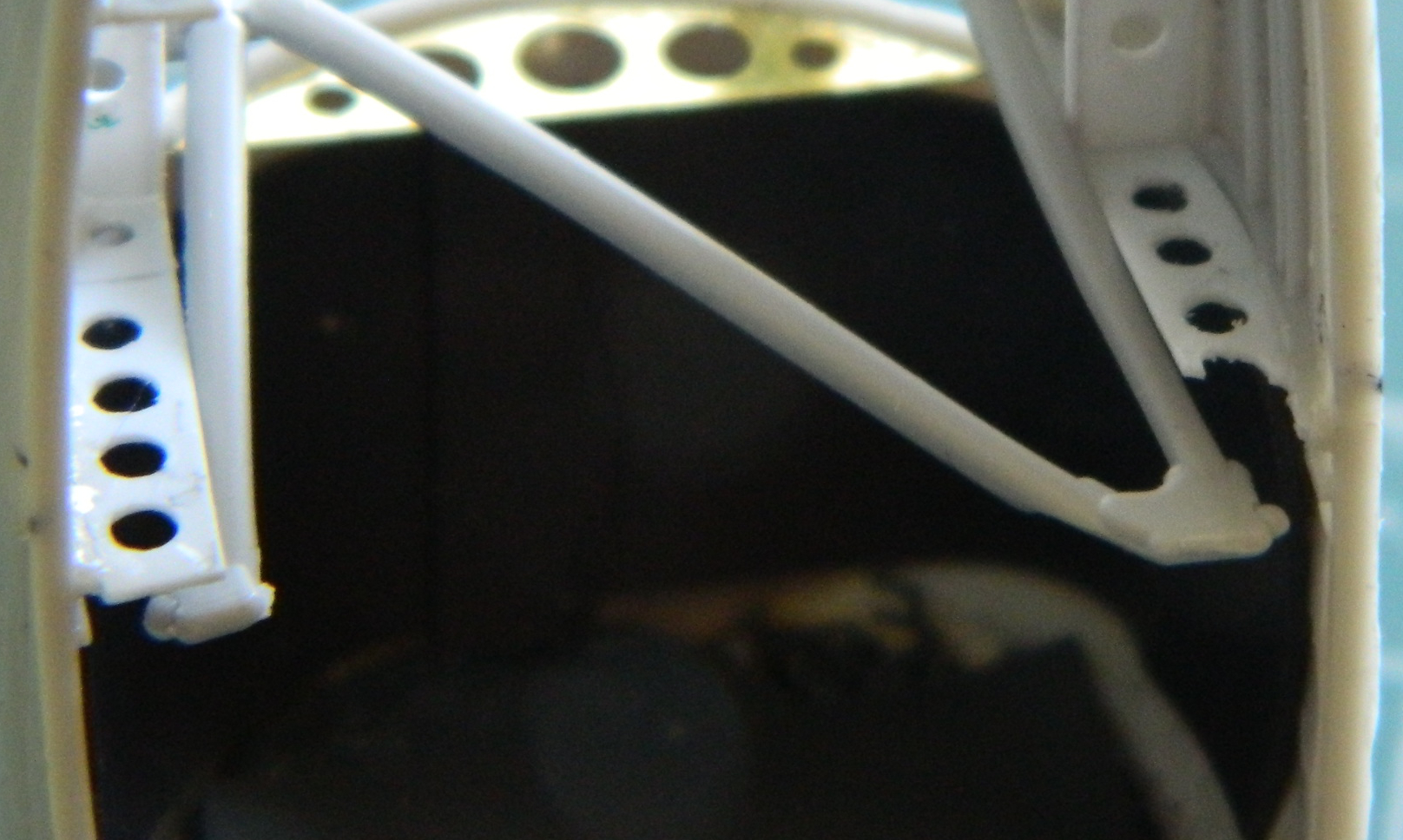

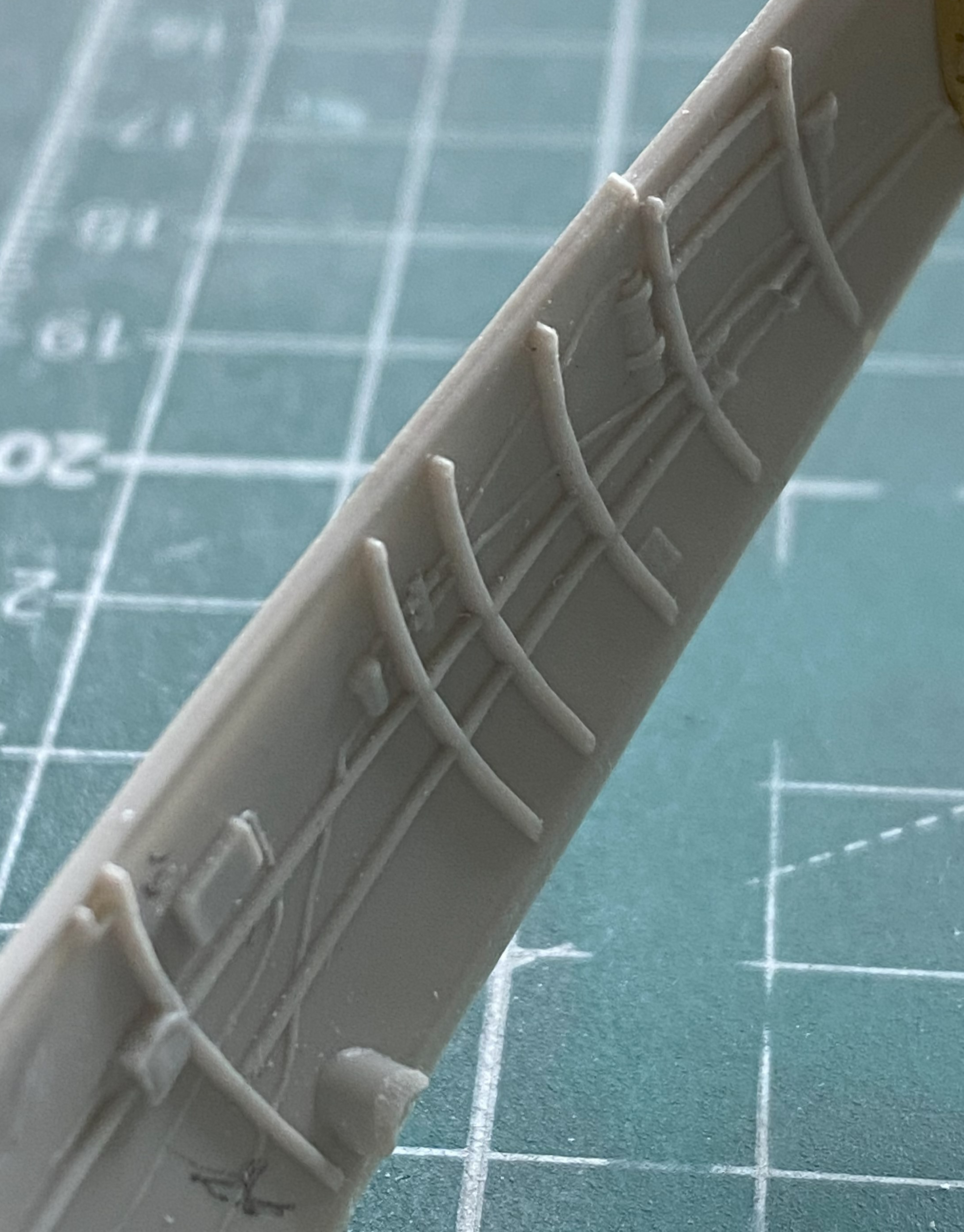

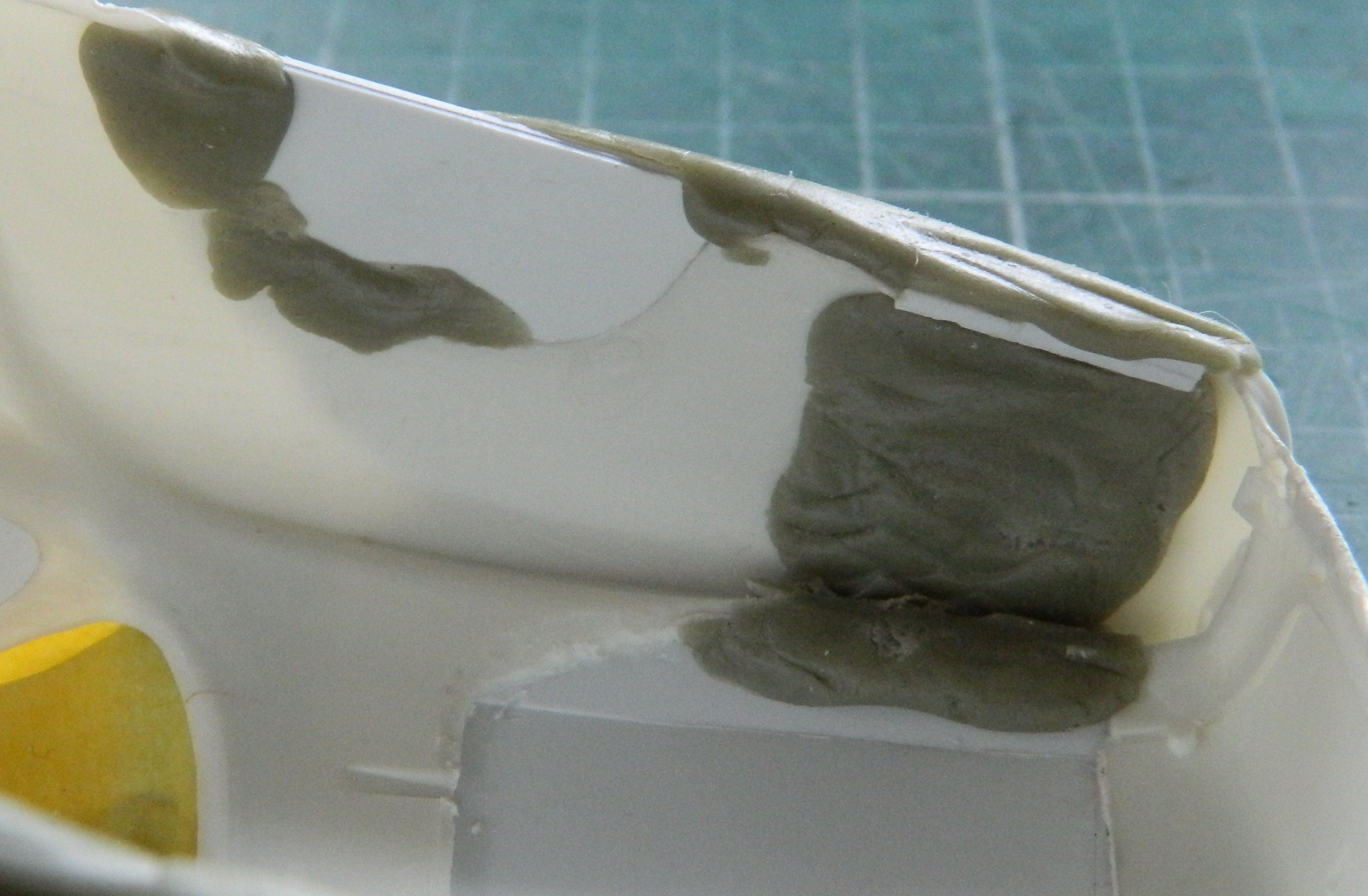

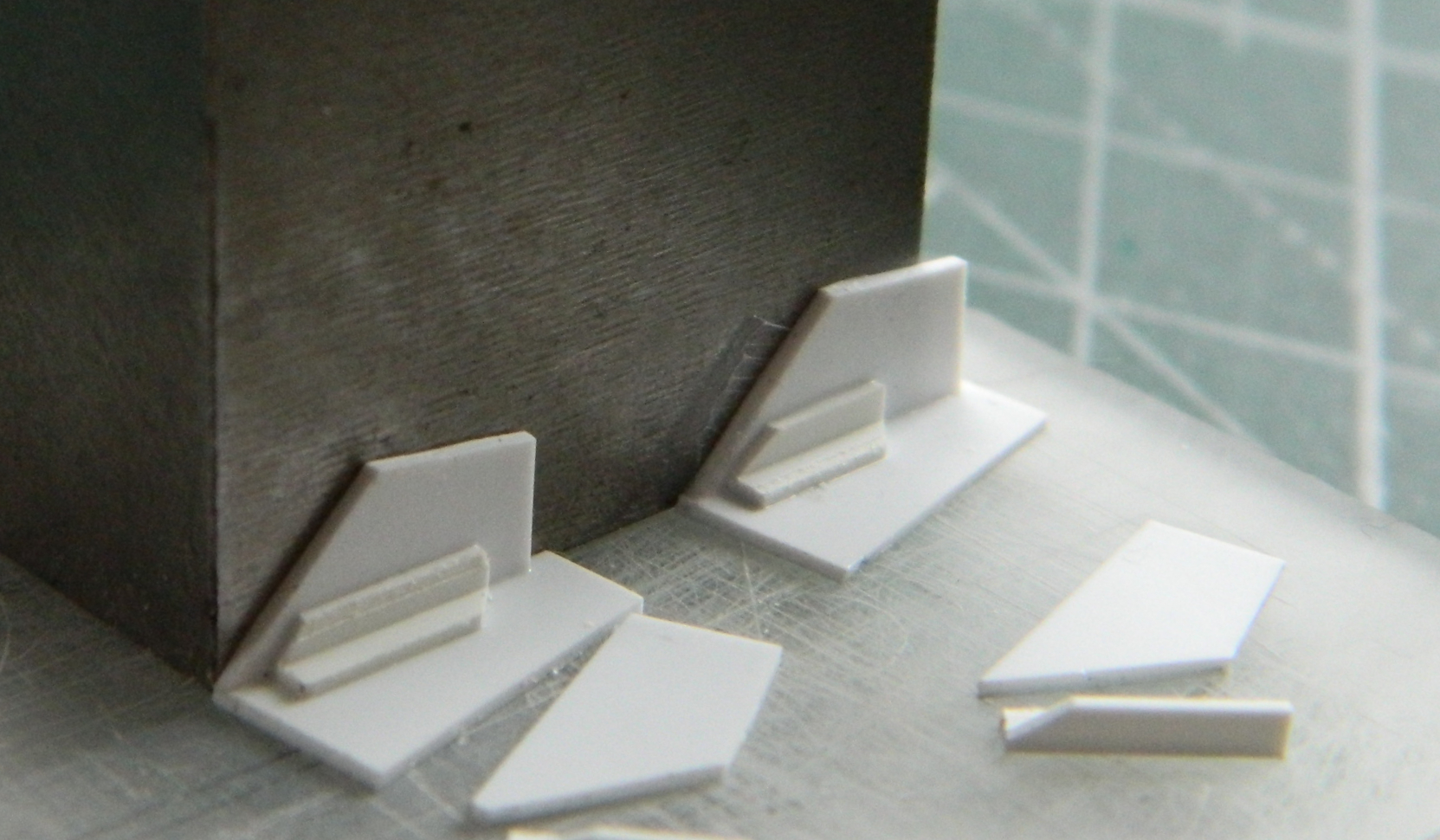

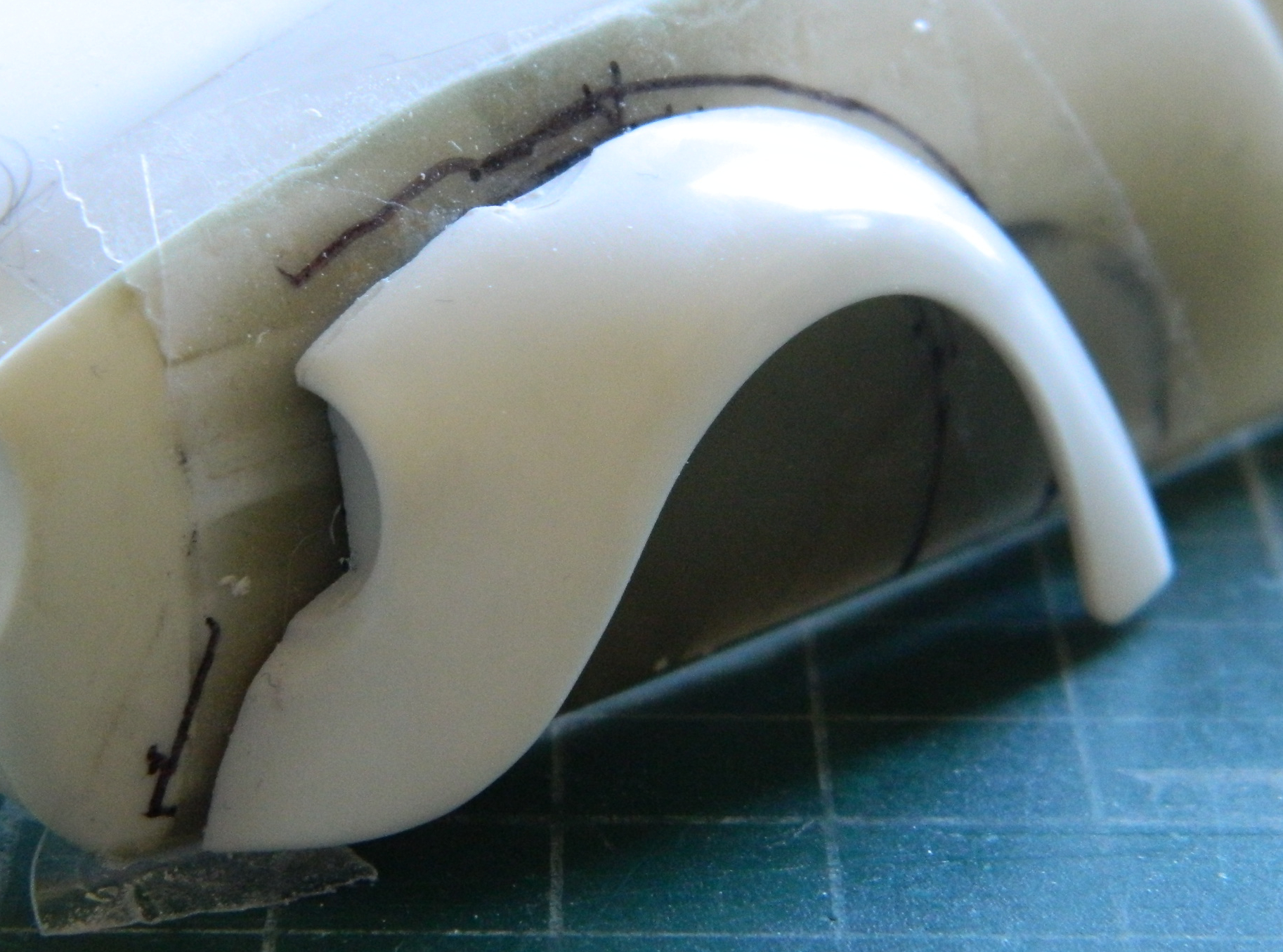

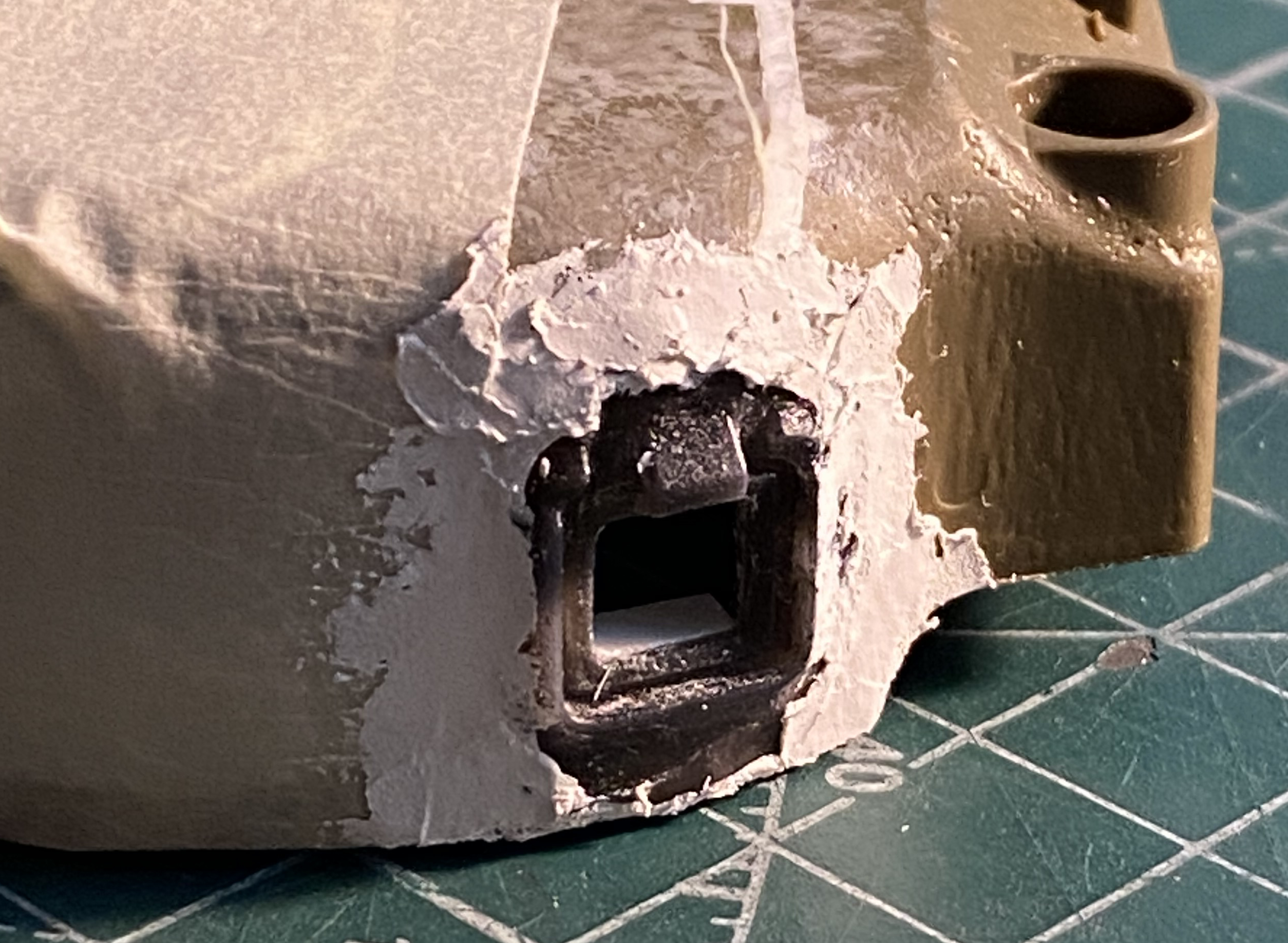

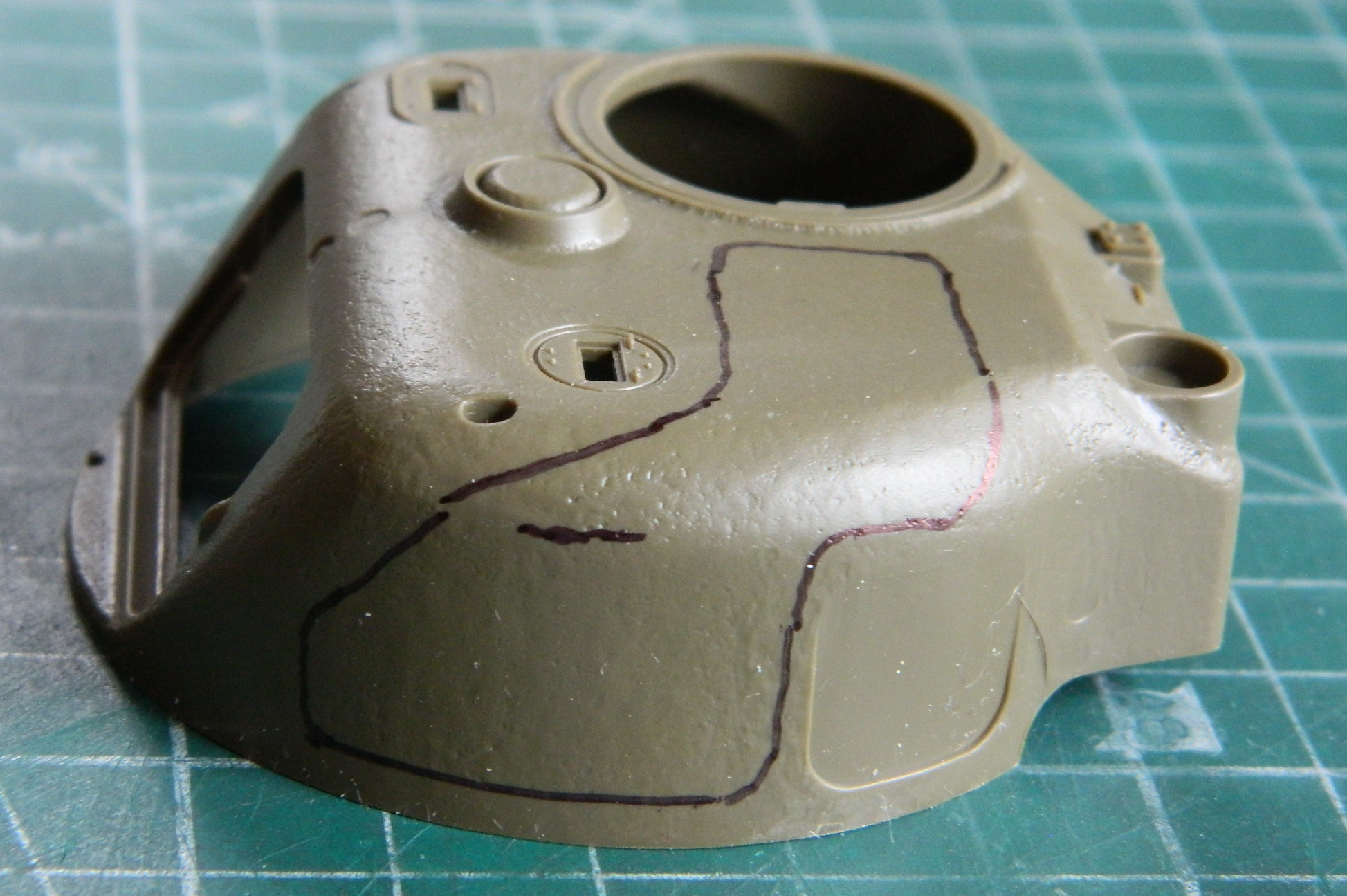

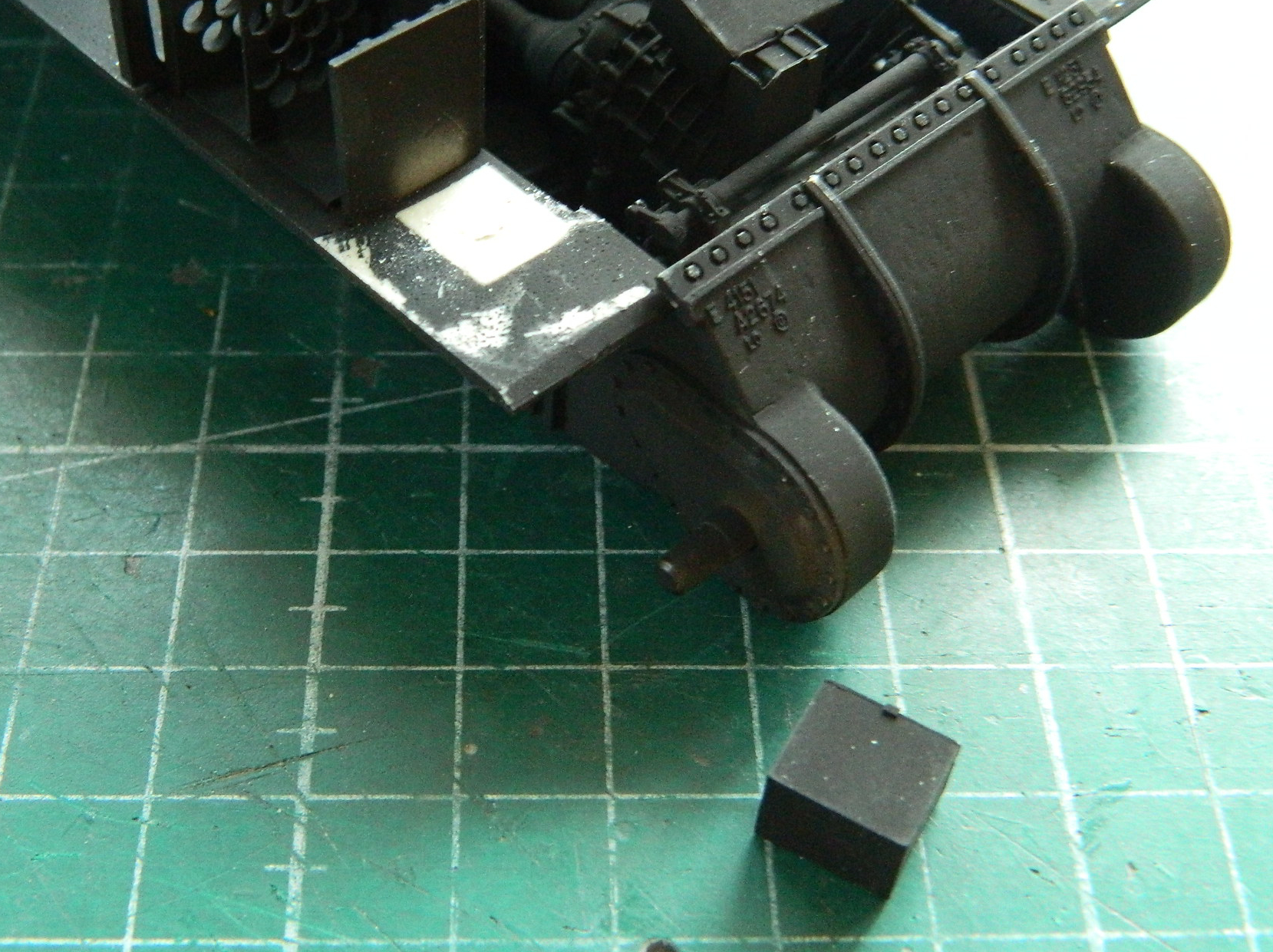

Then it was time to fart around…forever…with the landing gear. My initial notion of using the metal parts was set aside because the alloy is so malleable that working them was akin to trying to work the surface of cooked spaghetti (okay…maybe not that flexible, but after far too many times having to straighten something out I considered going to get tomato sauce and grated cheese) (couldn’t find the cheese and by the time I had, I’d sobered up, so…). I still had the plastic parts from the kit (which I’d assembled to act as a form so that I knew how far to bend the spag…er…metal parts), so I decided to use them instead and hope that this thing didn’t squat over time. I finished off almost all the parts when I found this:

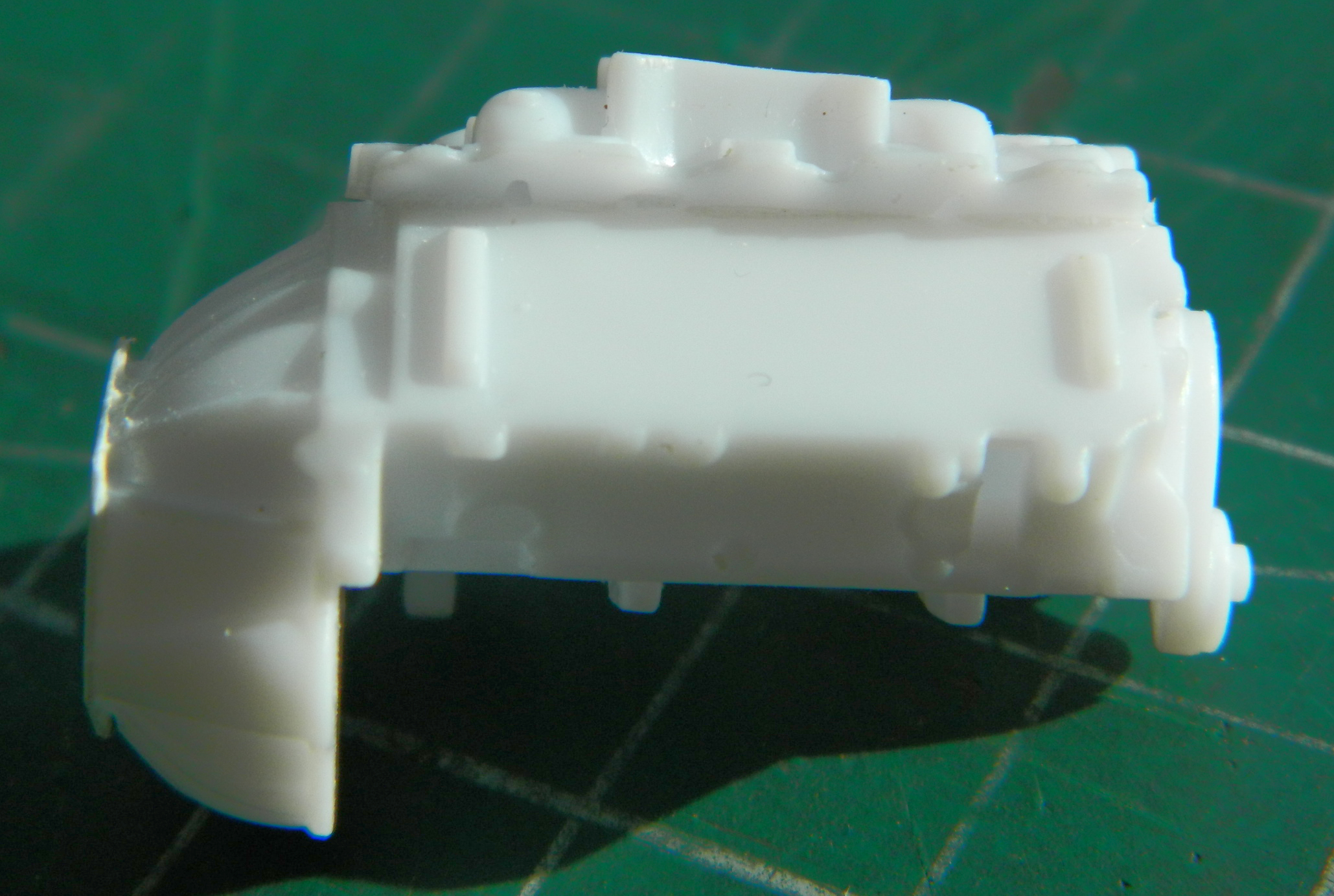

Most of you probably knows what a “short shot” is (and no…it doesn’t mean that). For those of you who don’t (or think it does mean that), it’s when the liquid plastic pumped into the molds doesn’t fill the void completely. That’s what happened (or didn’t happen) to the lower part in the above photo.

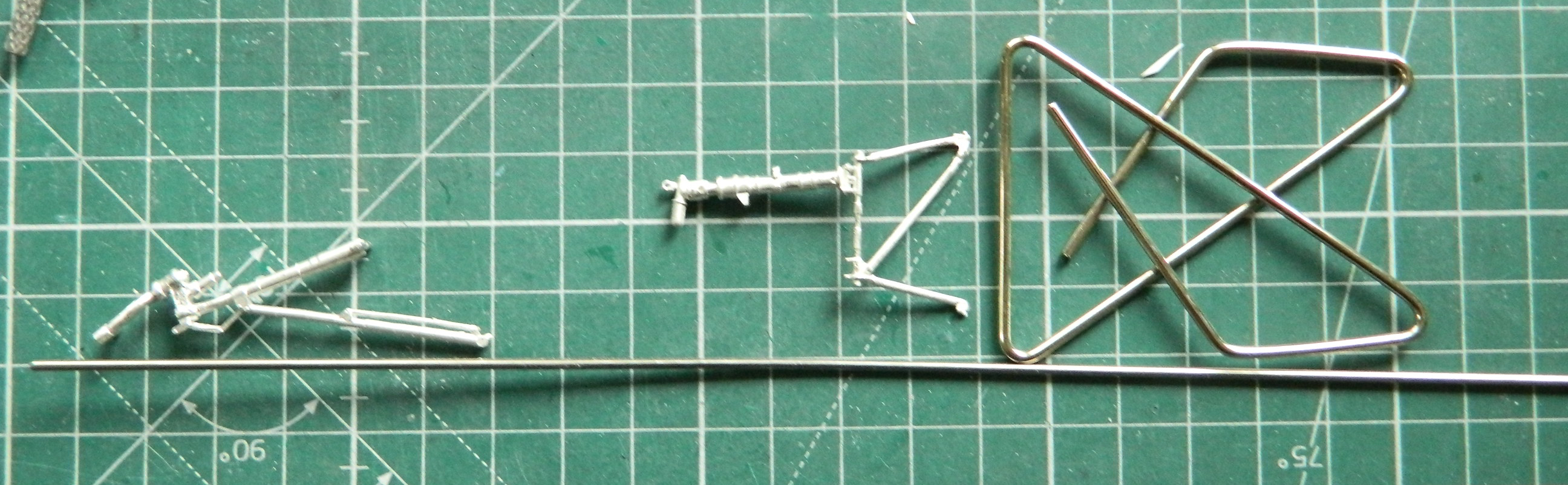

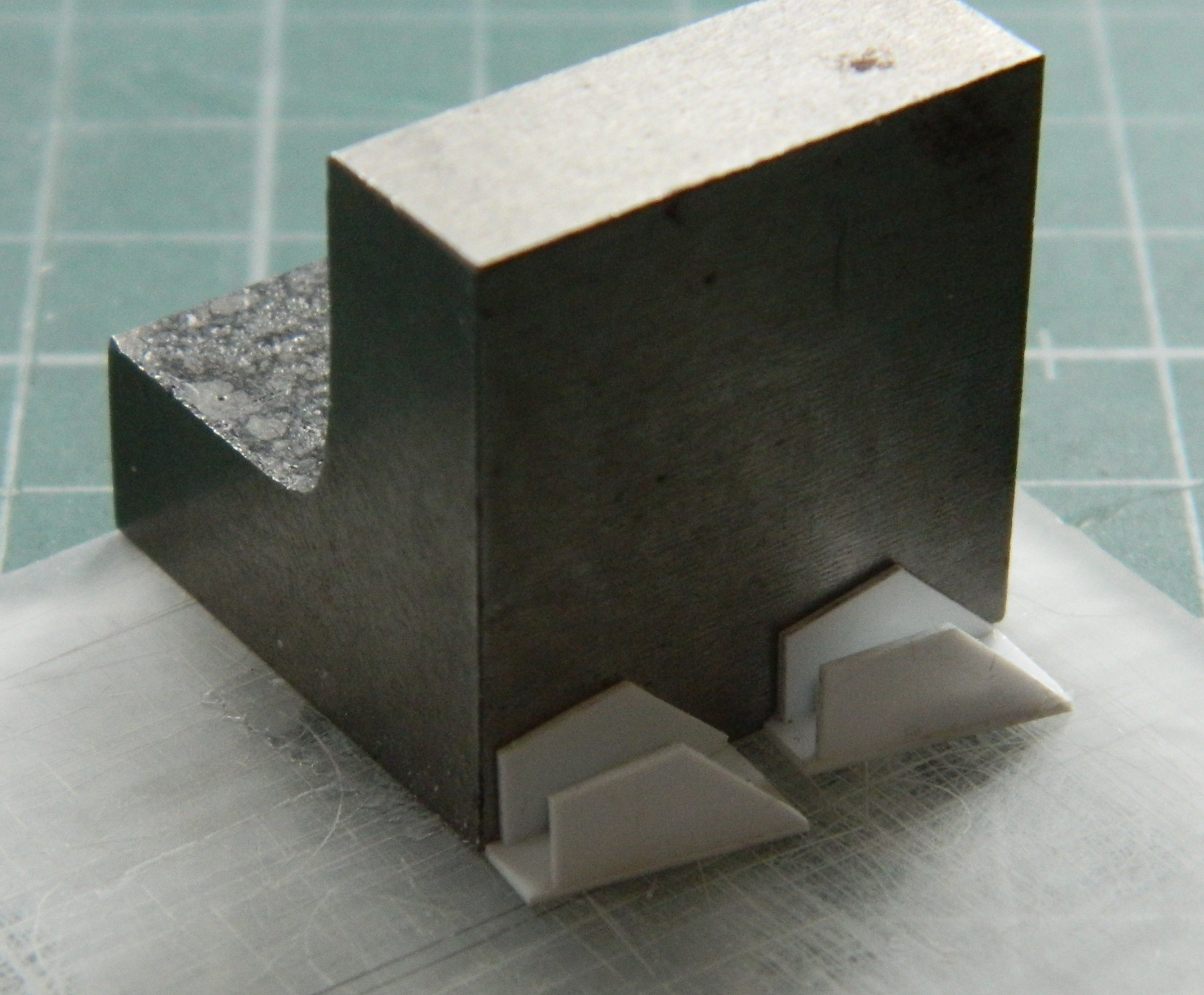

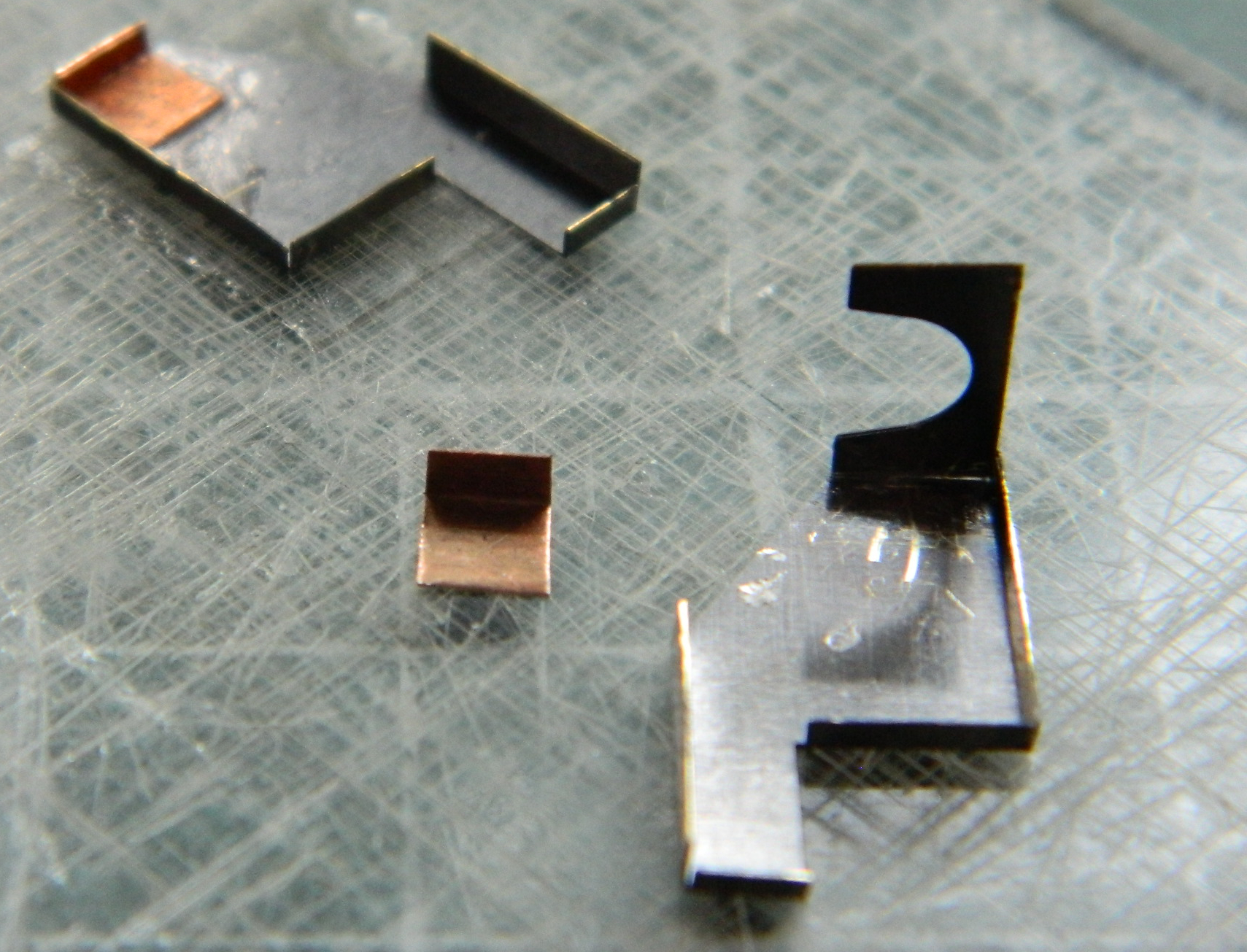

Fine. I’ll use the damned metal parts, then. (And yes…I pouted.) (Probably more because I did sober up but some of the lower lip extension was because I had to change my mind back.):

I can be pretty funny sometimes. When I took the above photo, I thought I had everything finally aligned.

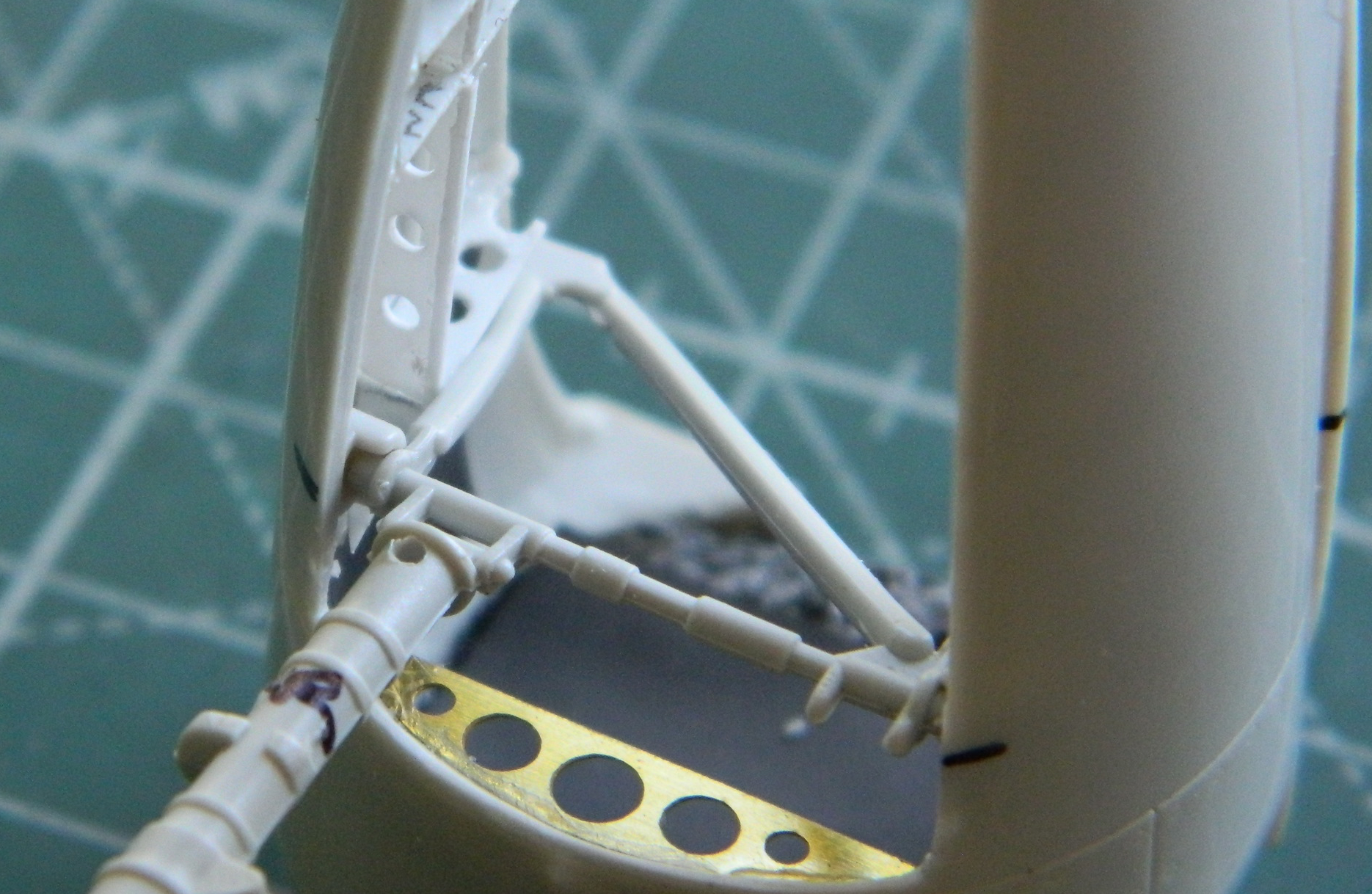

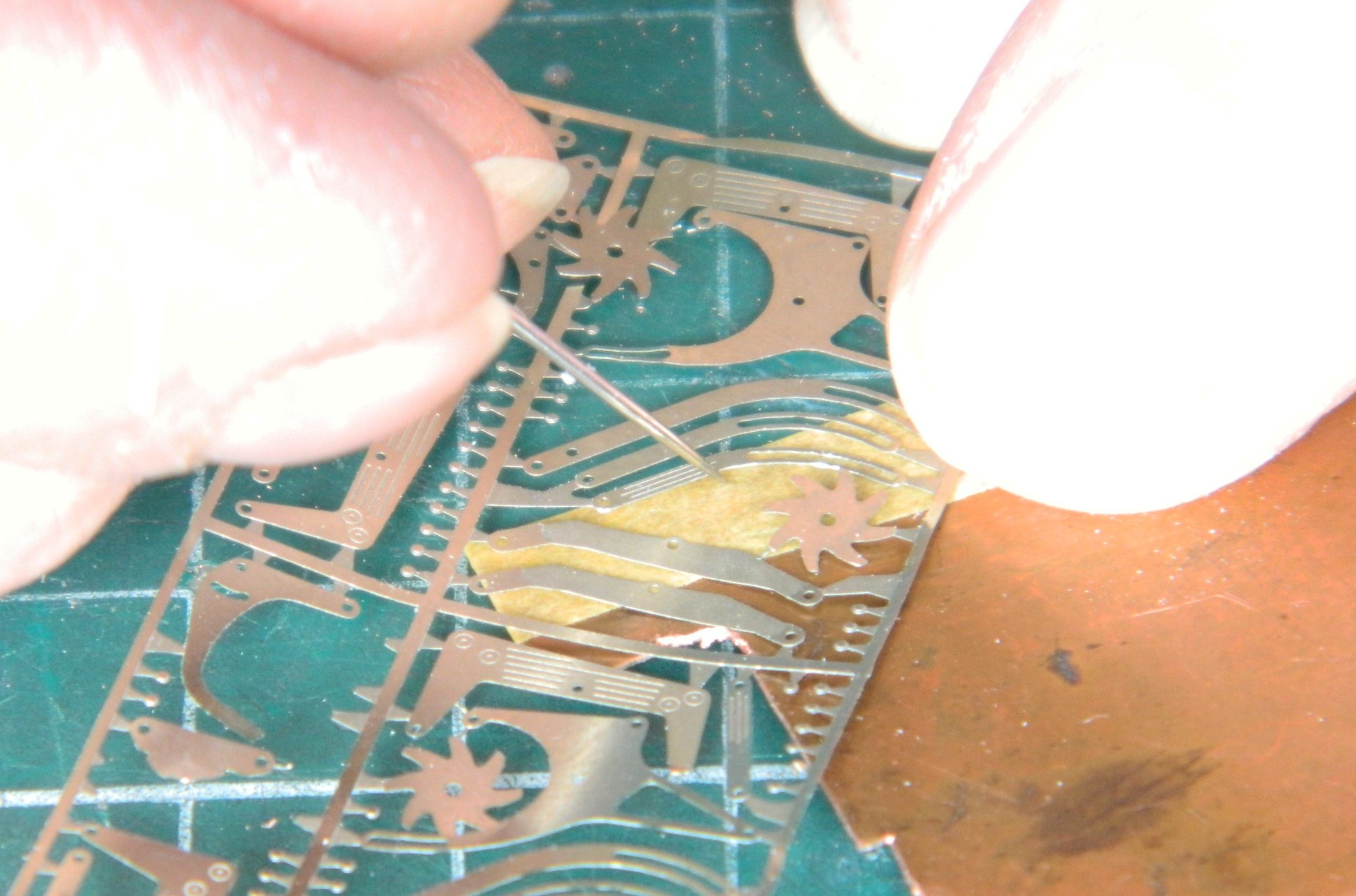

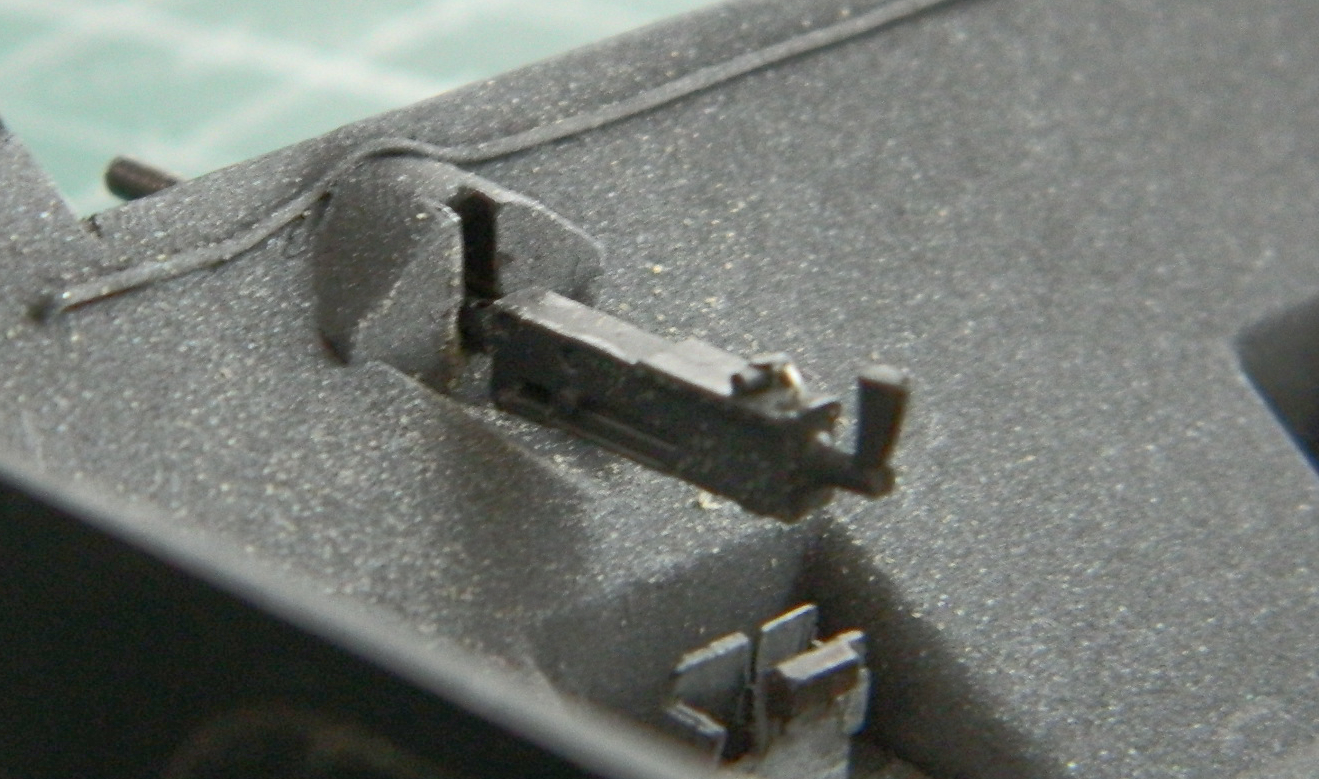

I used the kit’s oleo extension arms on the main gear, but used the arms from the PE set for the nose landing gear (that’s the brass-colored part):

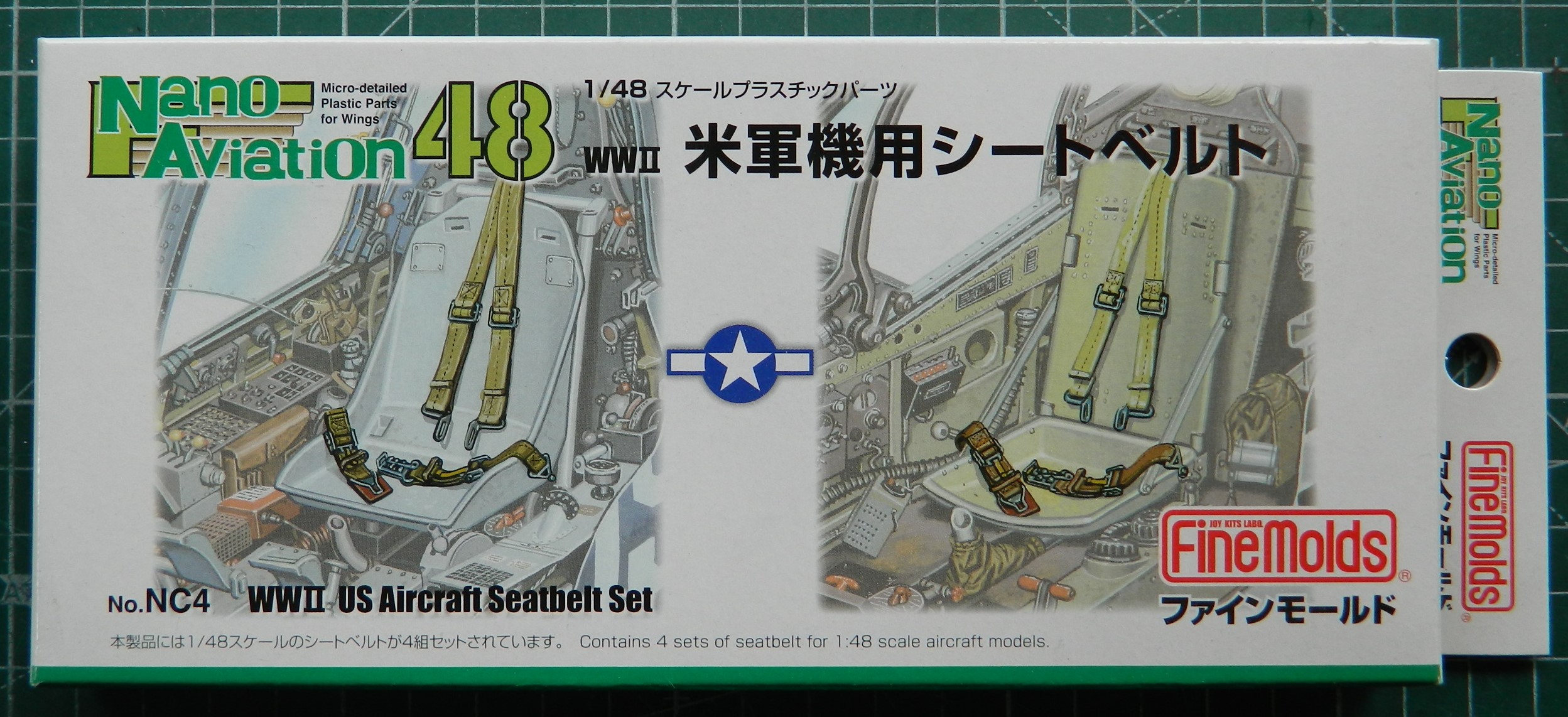

And just as an aside (and because I don’t have a lot to show here for this month, so it’s filler), a few years ago I heard about these, bought a set (which comprises four separate sets of what’s pictured below), and plan to use them on this build (which, with my typical aplomb, I totally forgot that I had until I was looking for something else):

They’re nicely molded with good detail. I’m probably going to have so much fun bending and shaping what needs to be bent and shaped. We’ll see if the effort is worth the result.

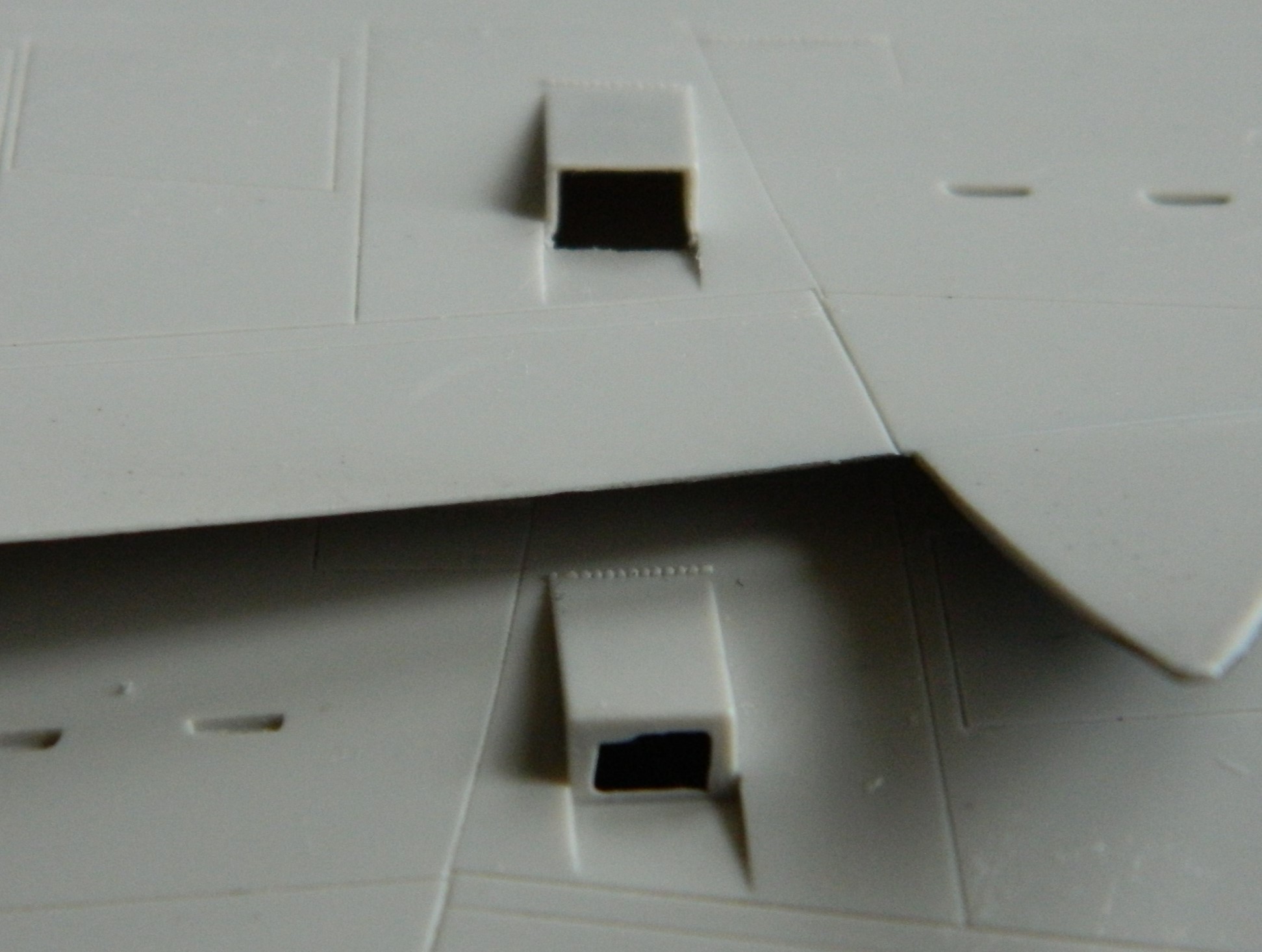

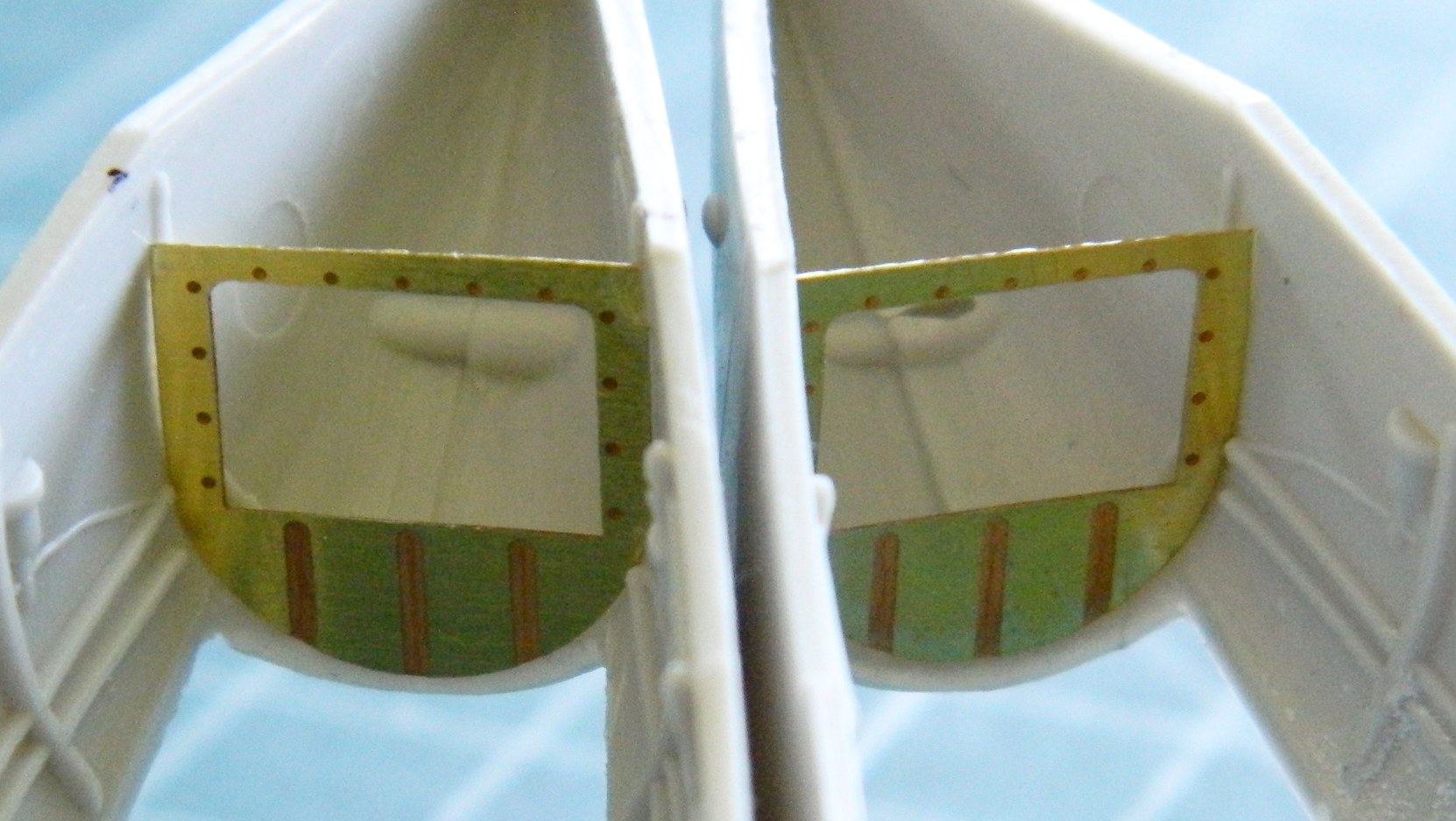

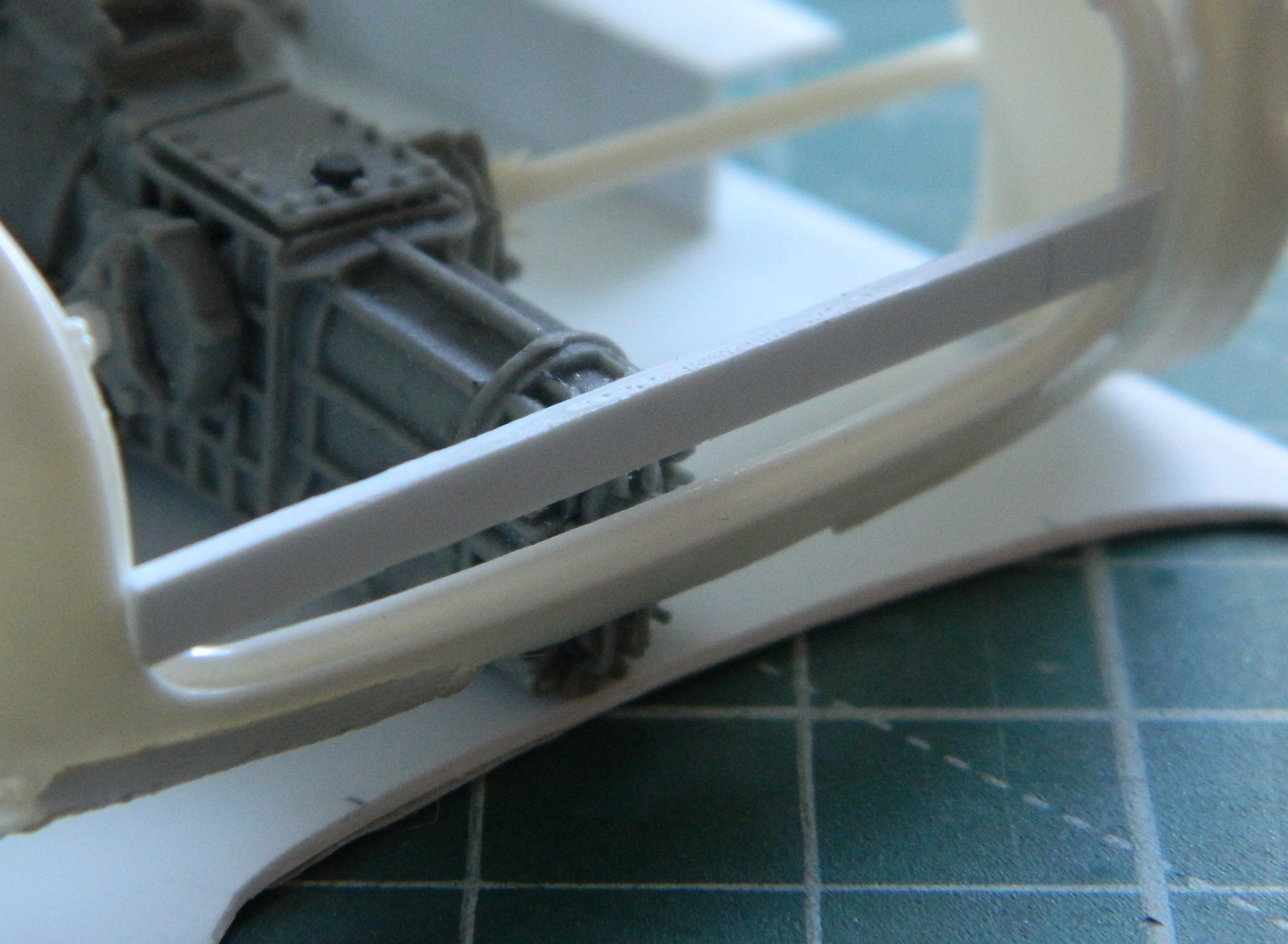

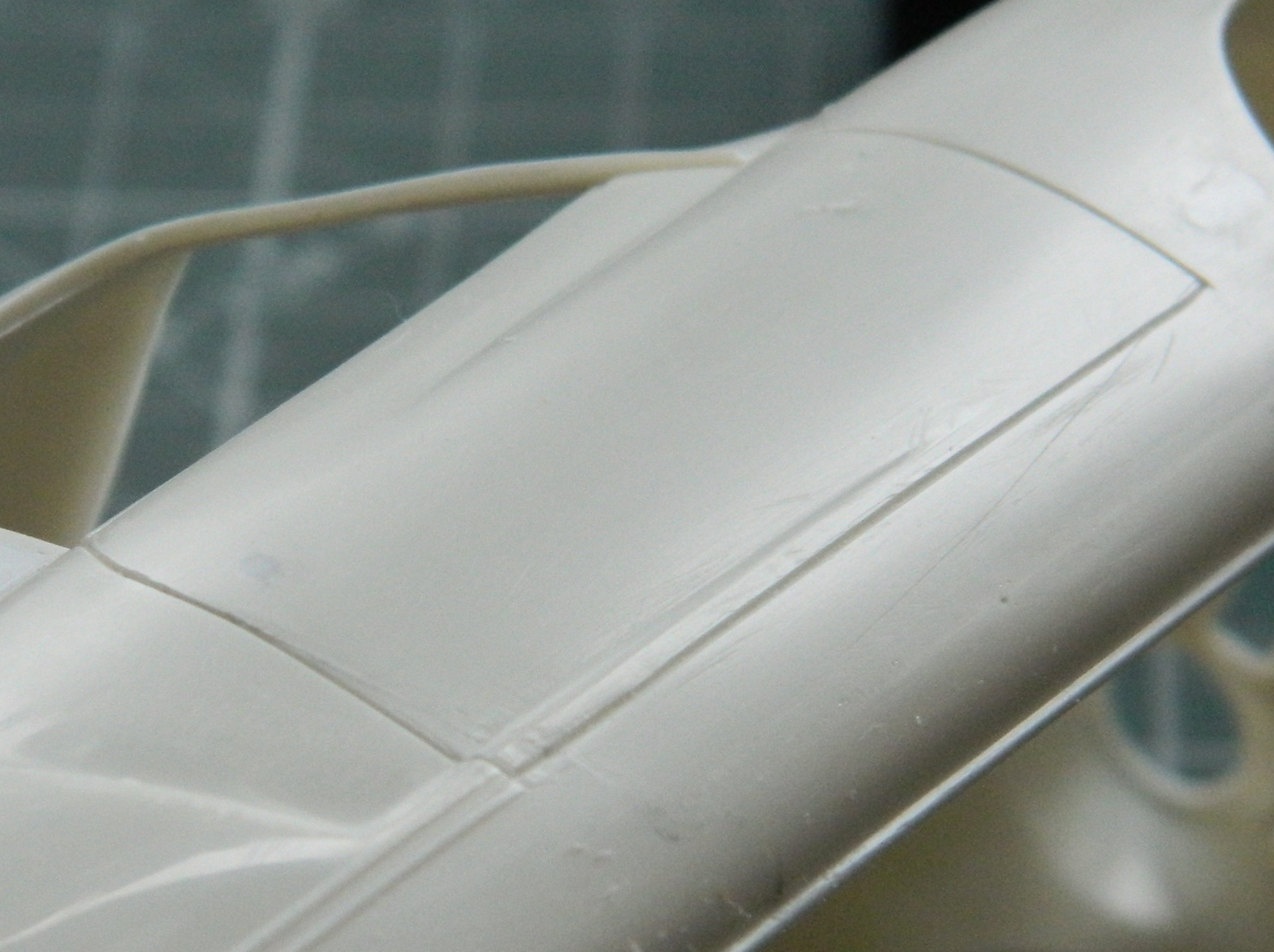

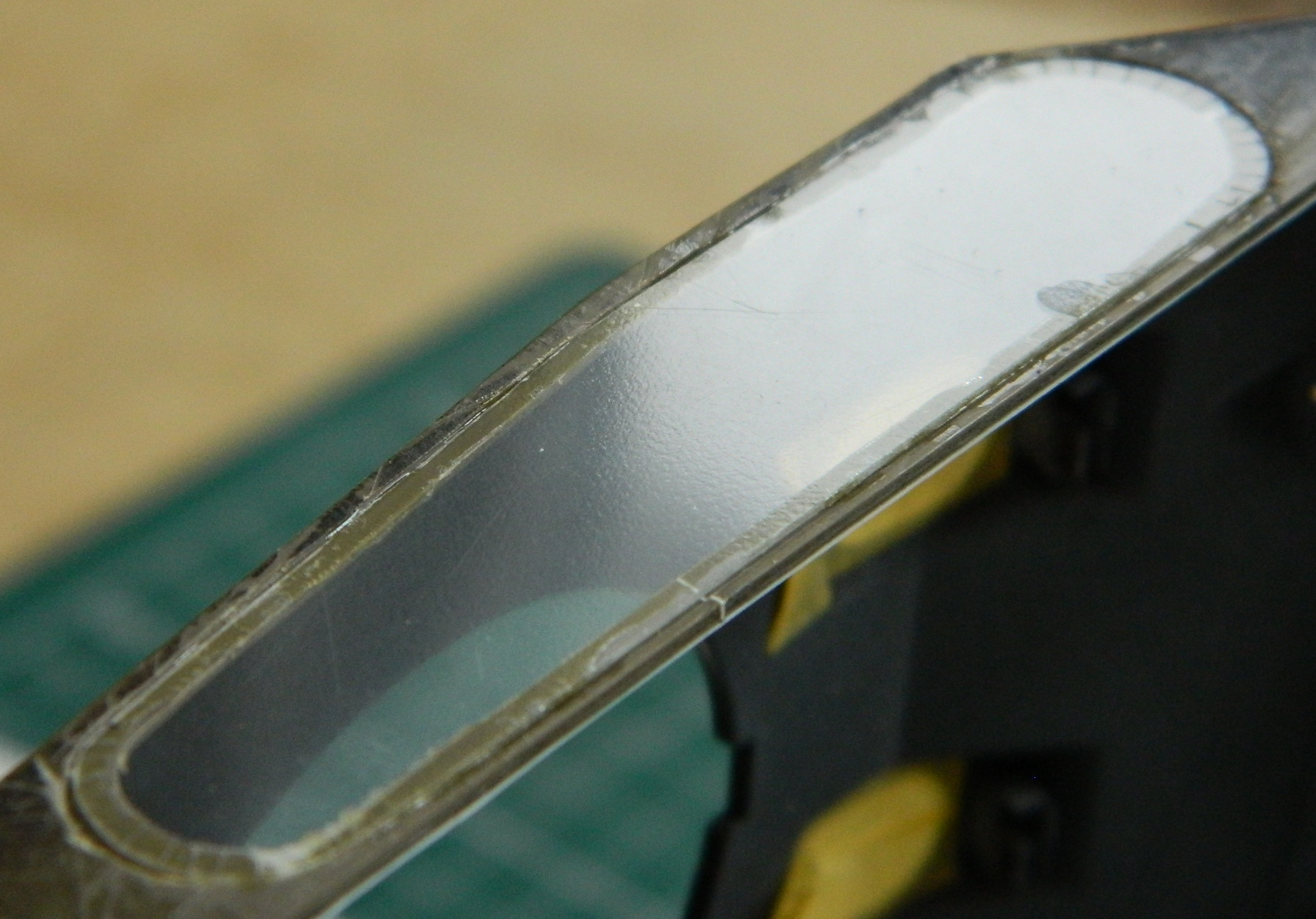

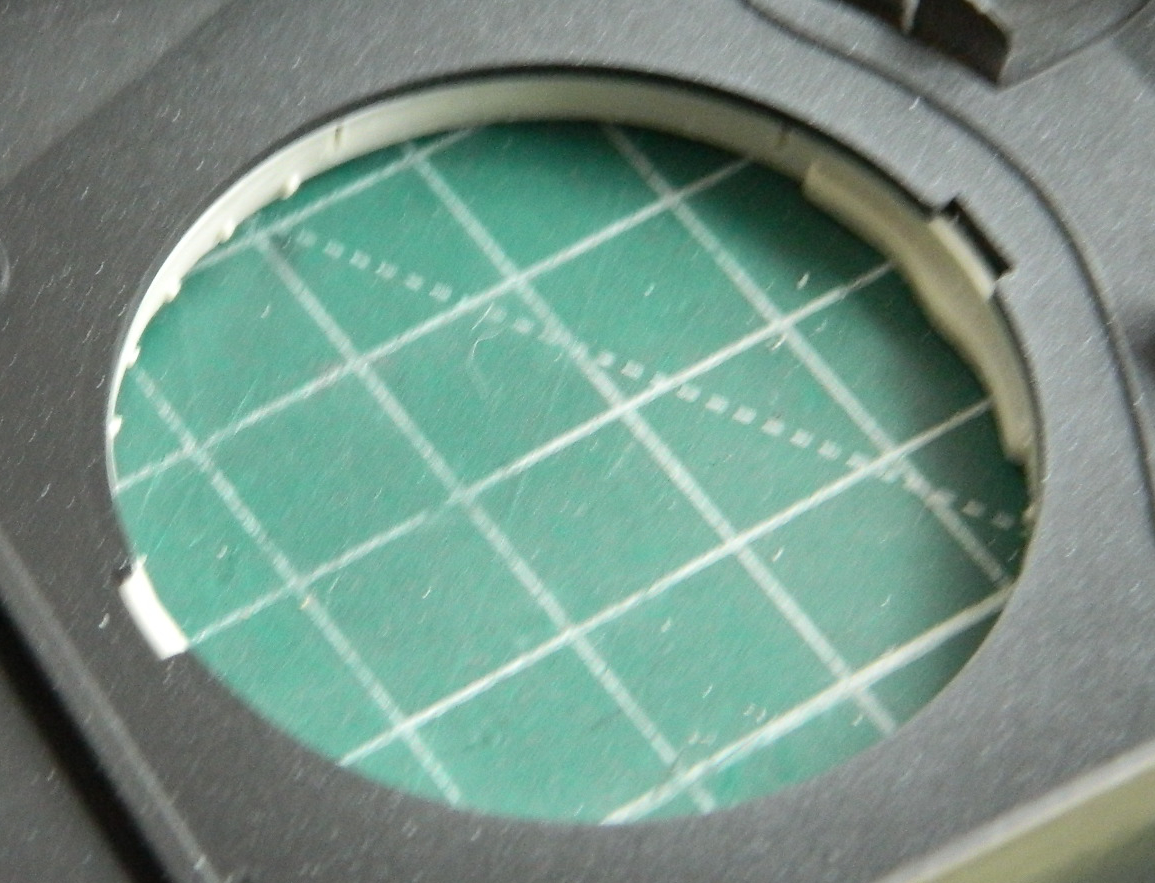

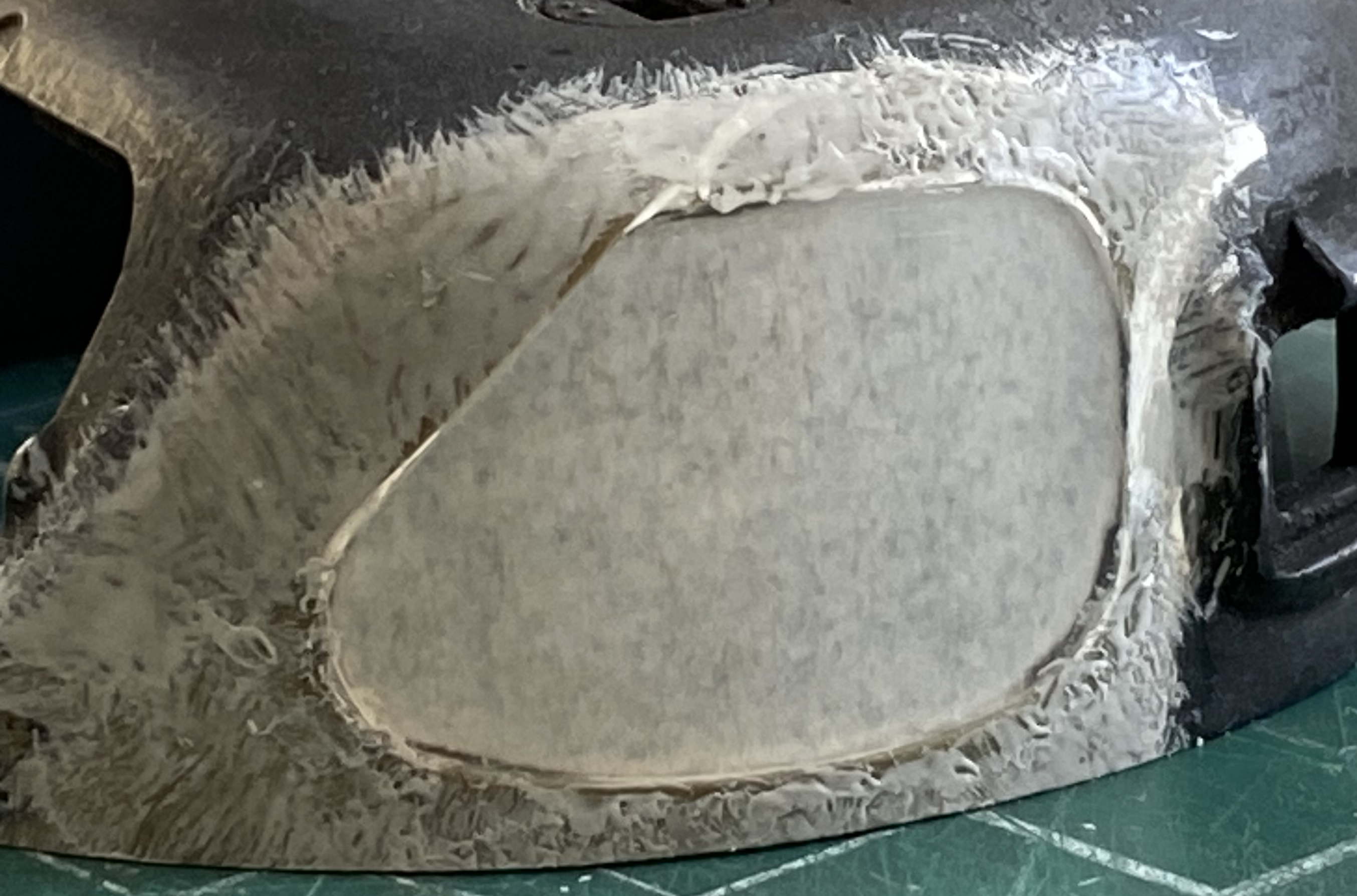

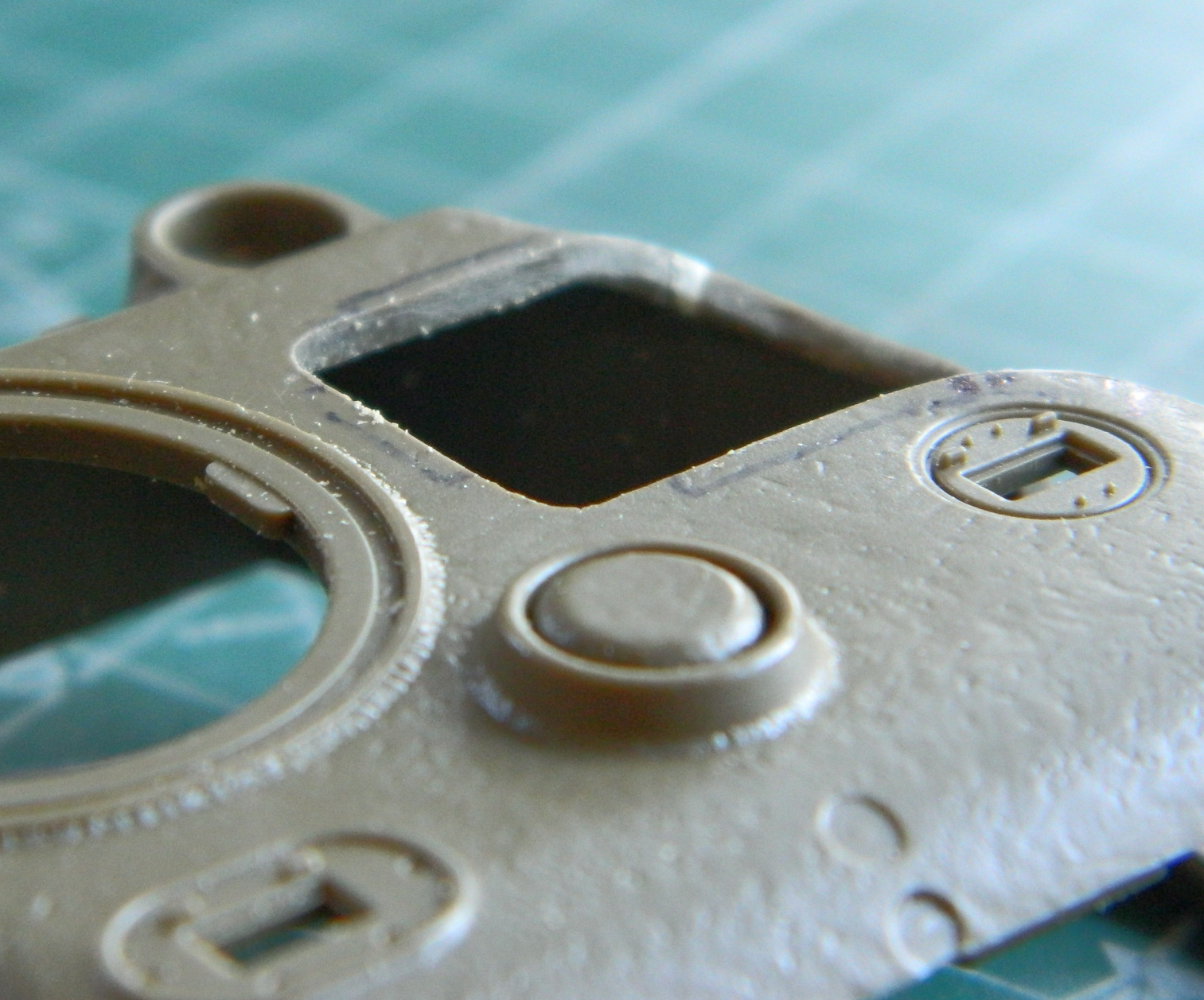

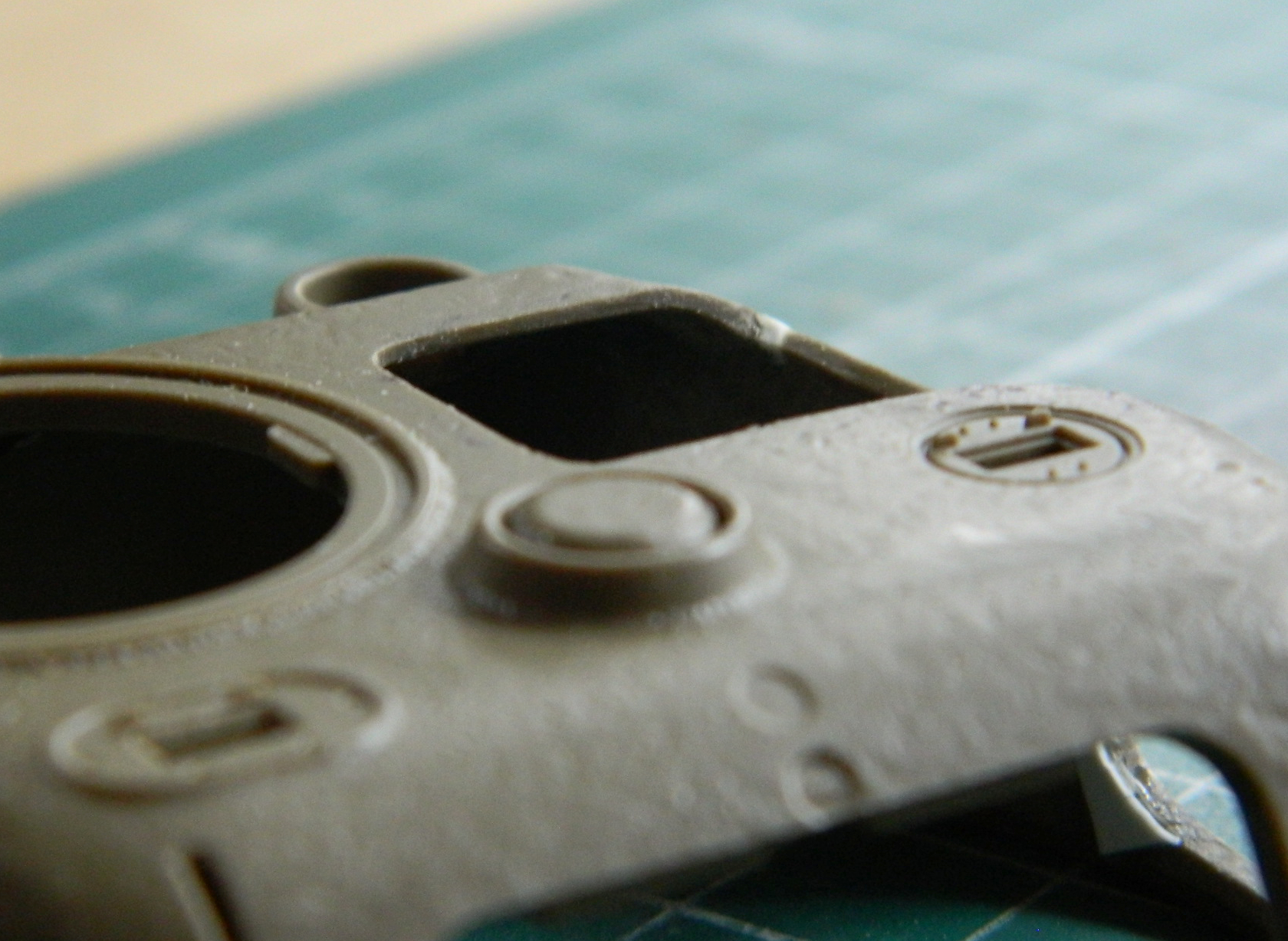

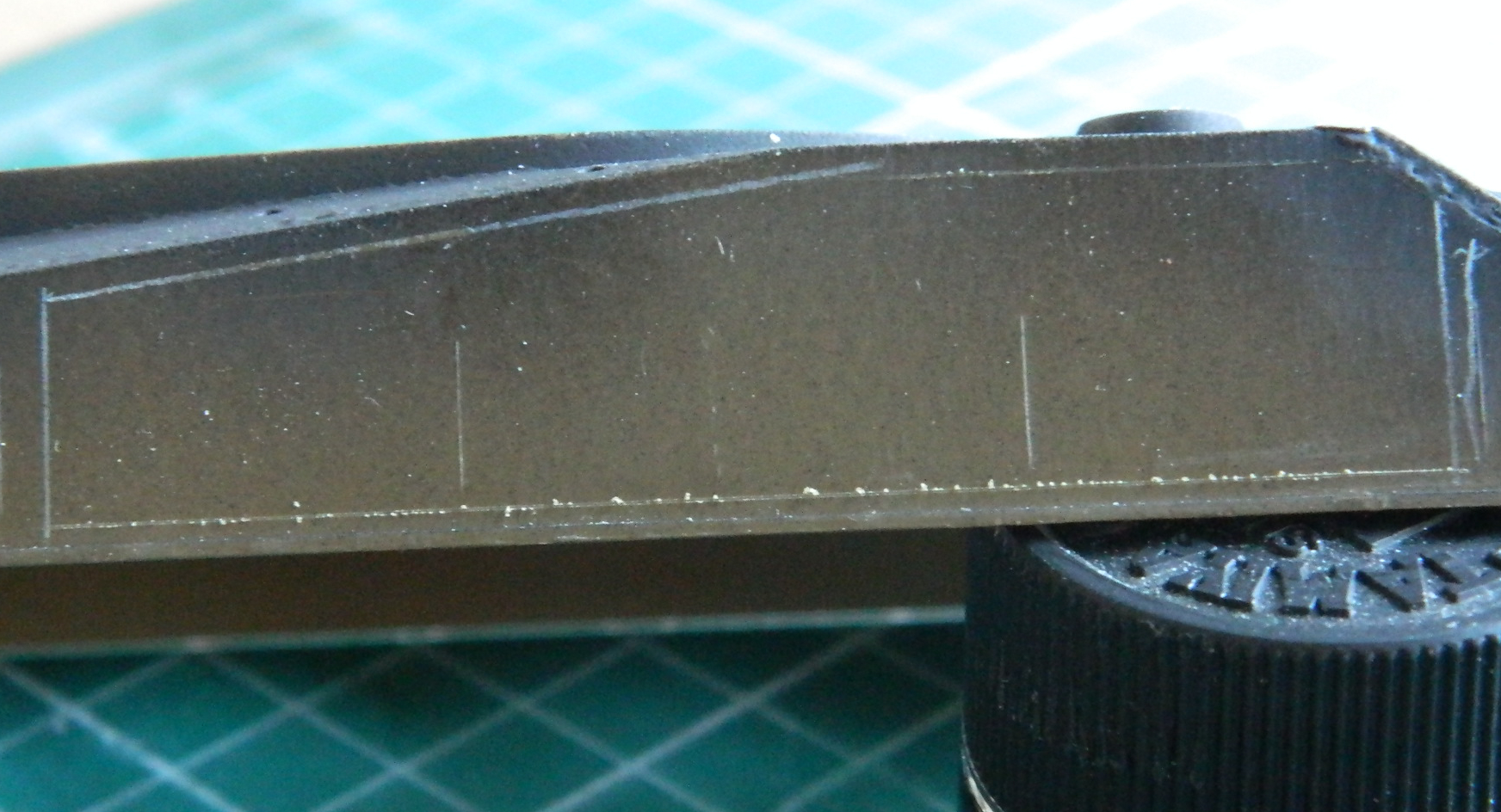

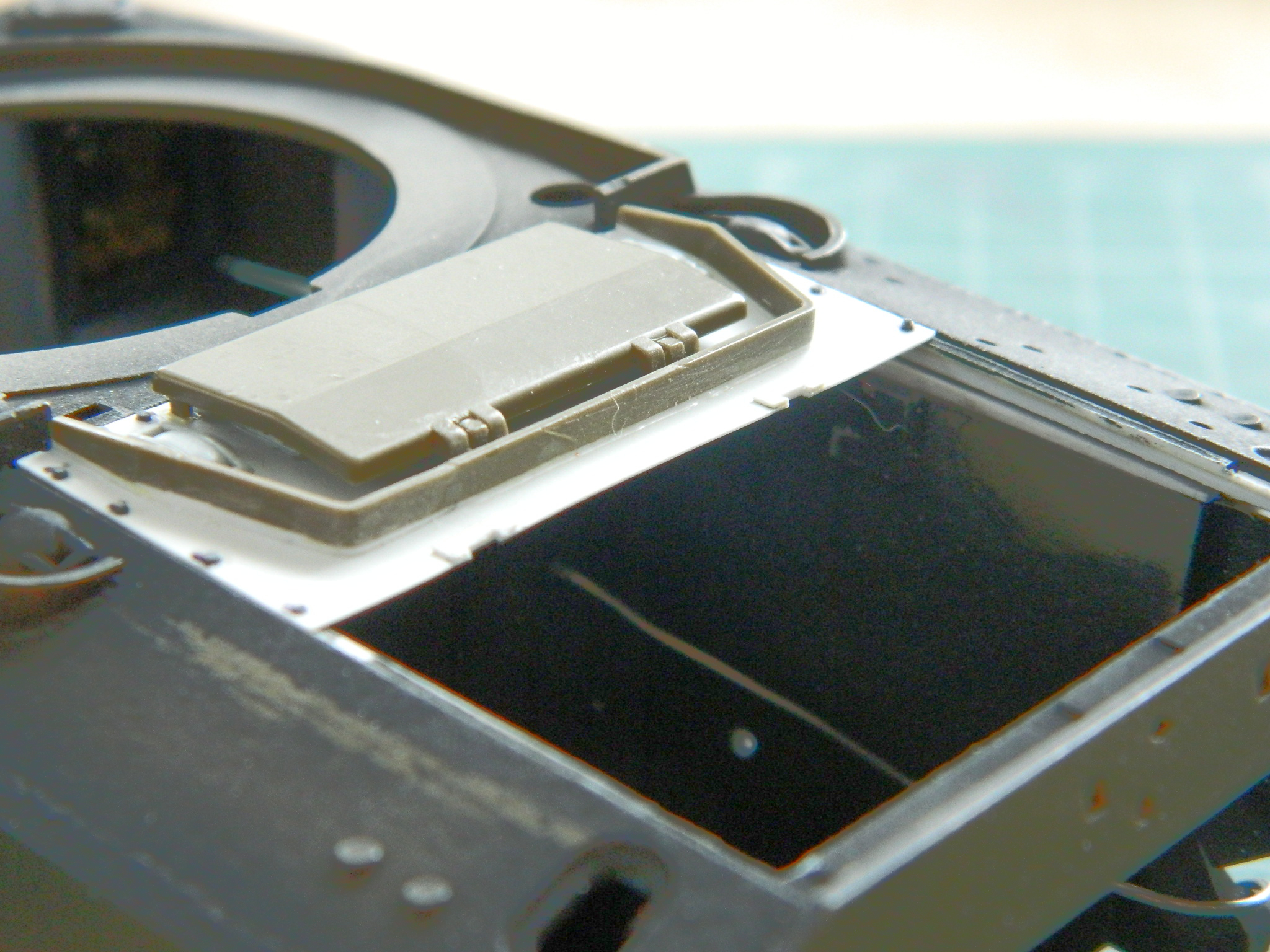

There are outlets for the oil coolers and the covers for the outlets are variable. The PE set offered replacements for what’s molded onto the wing tops but I decided to see if I could thin out what’s there sufficiently:

Yeah. That’s sufficient.

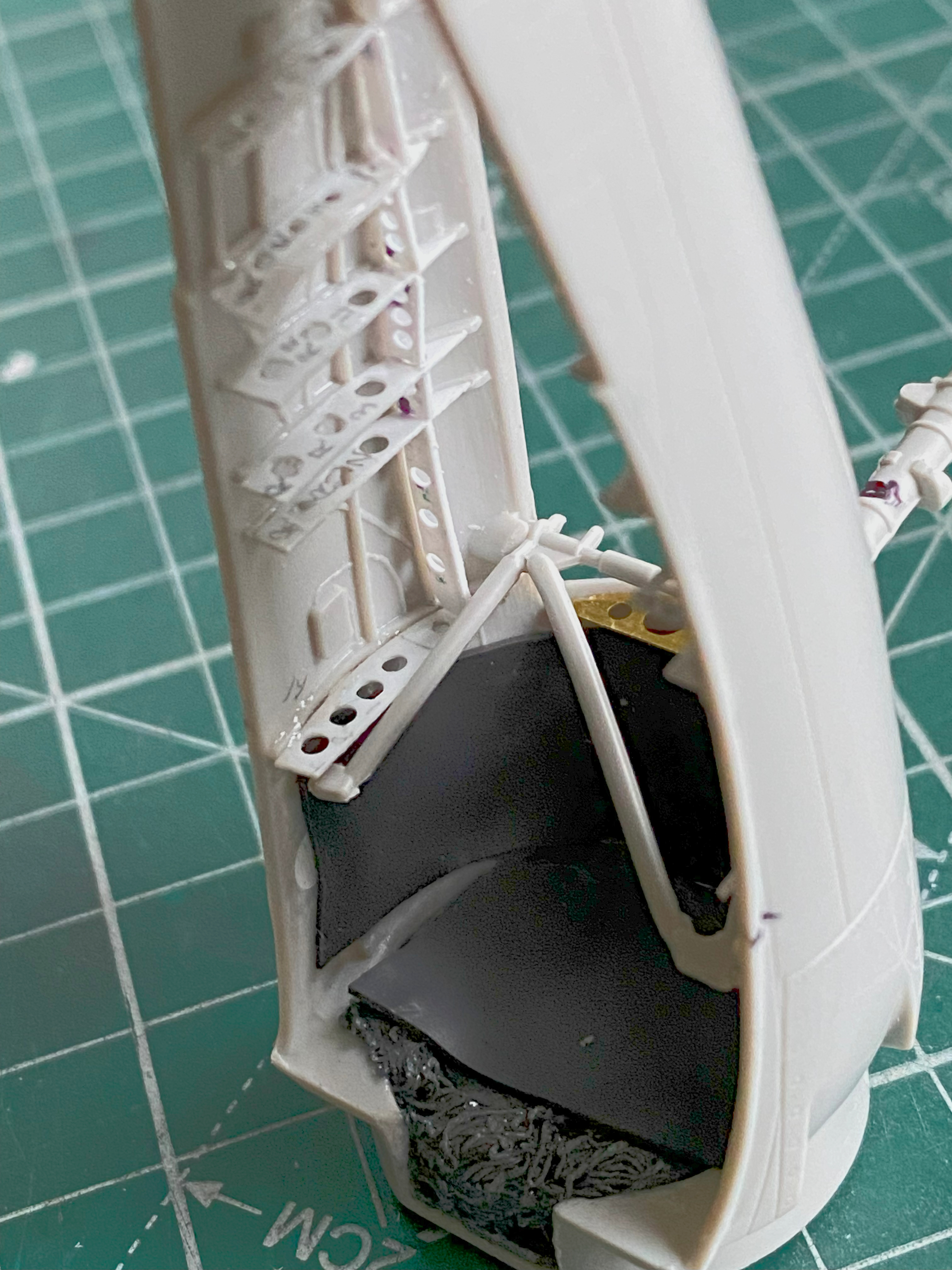

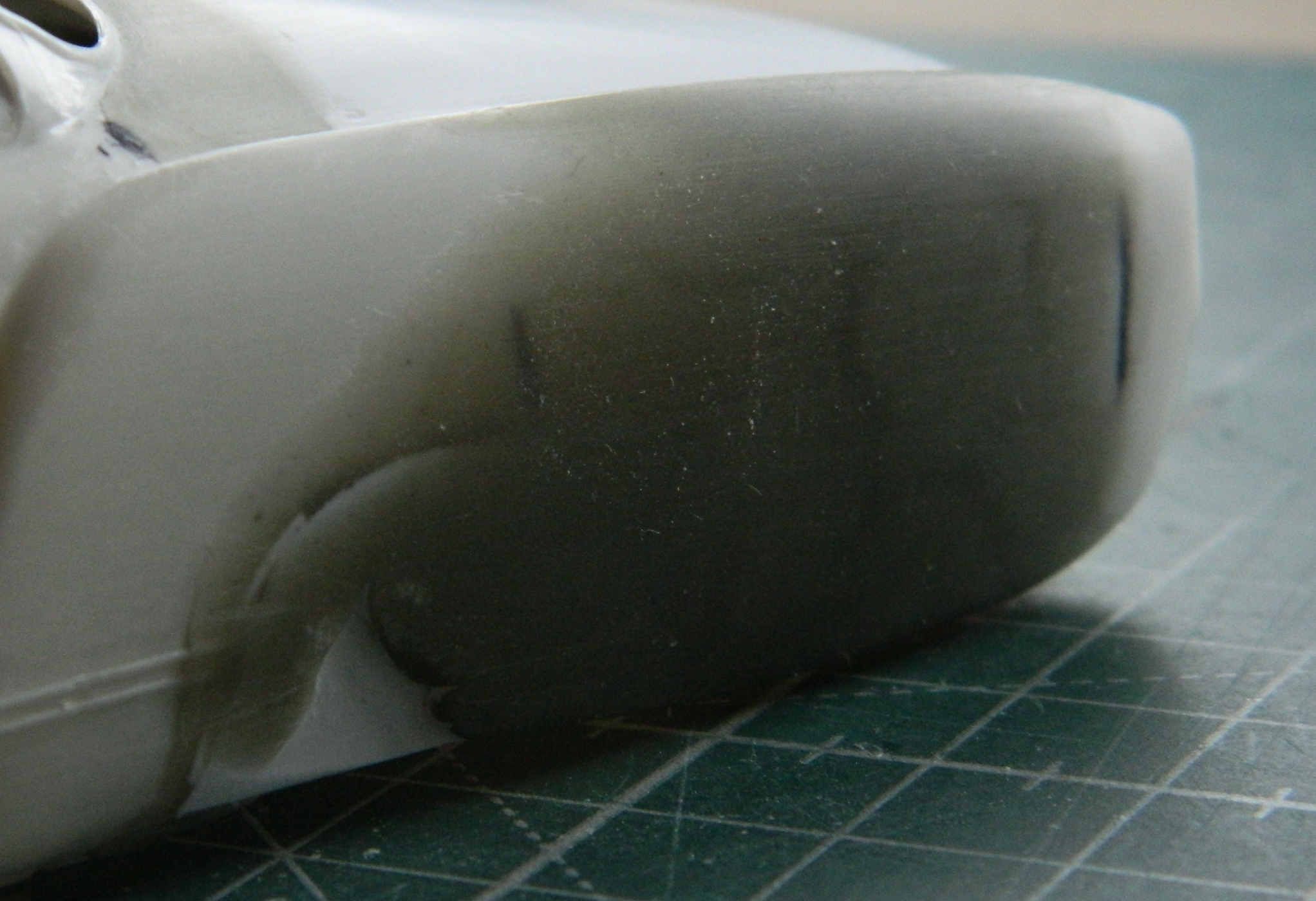

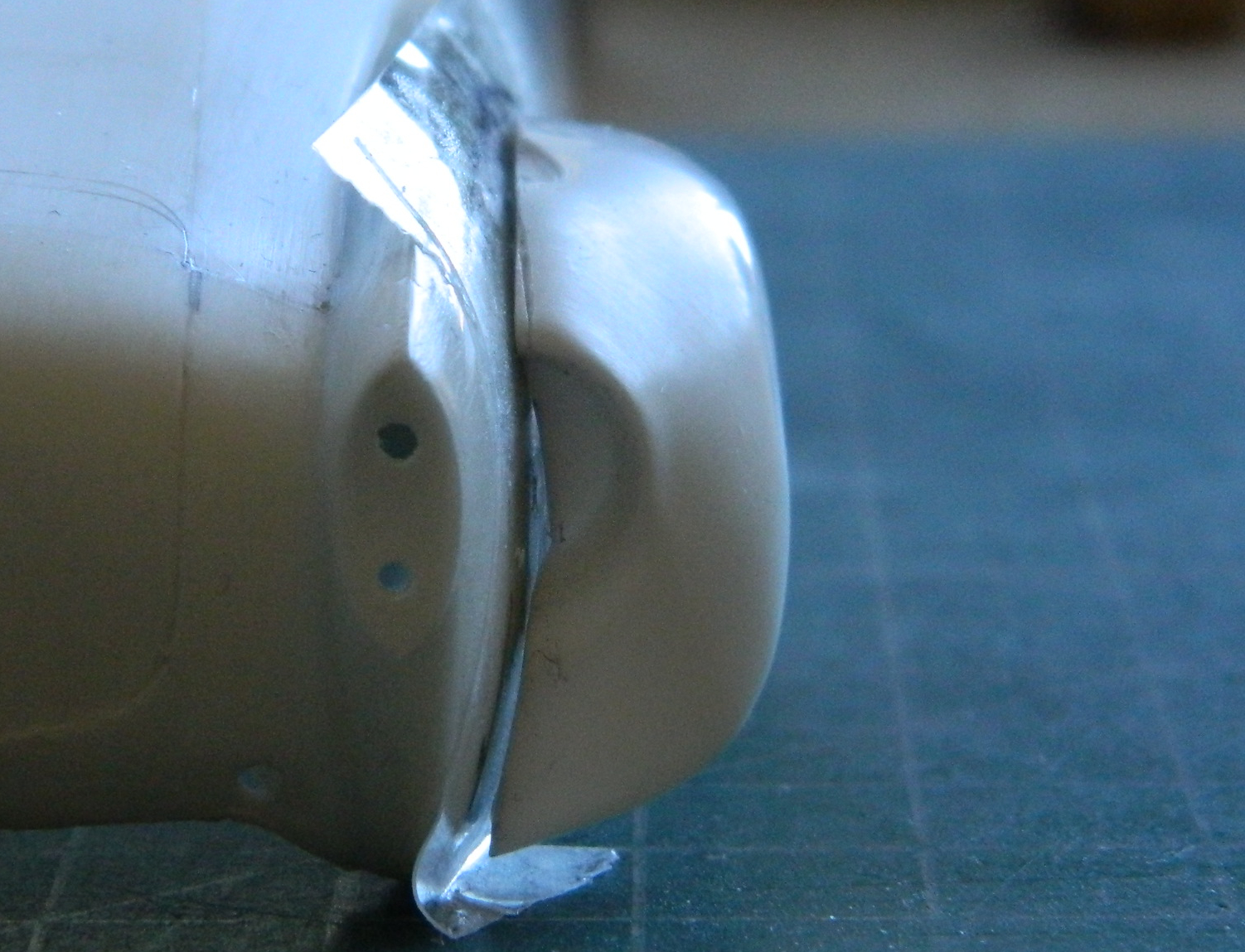

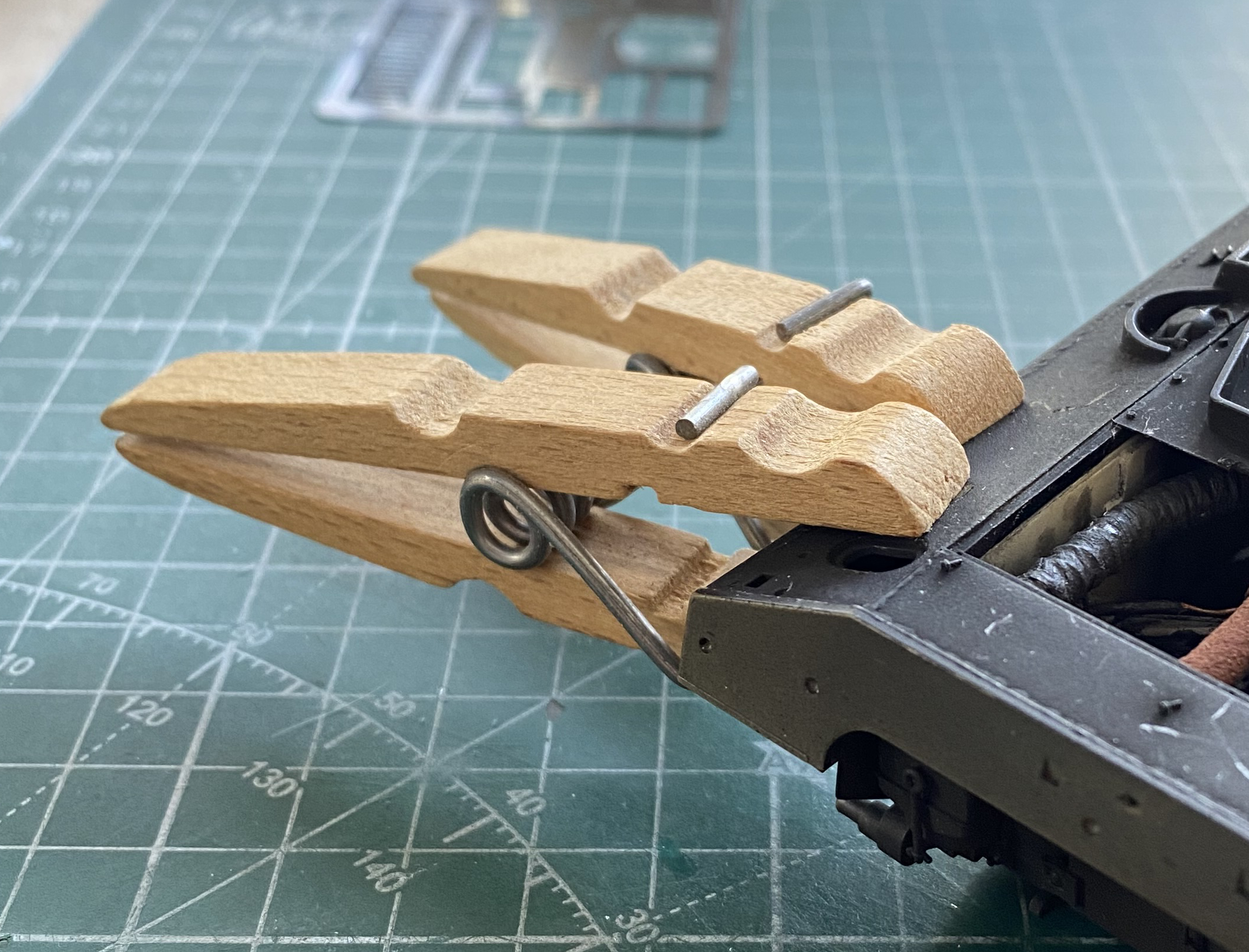

While doing the skull sweat regarding when the landing gear is permanently attached, I realized that trying to get the stupidly flexible metal landing gear inside the bays, things were going to be bent and badly so. Though I prefer to add things as delicate as these are as close to the end of the build as I can, that’s not going to work this time. Initially I thought it was because they’re so sodding bendable. Then when I tried to feed them into the bays from underneath, which is how they’d get attached later on, I discovered that they didn’t fit through the opening. ::sighs:: Okay, I’ll add them now:

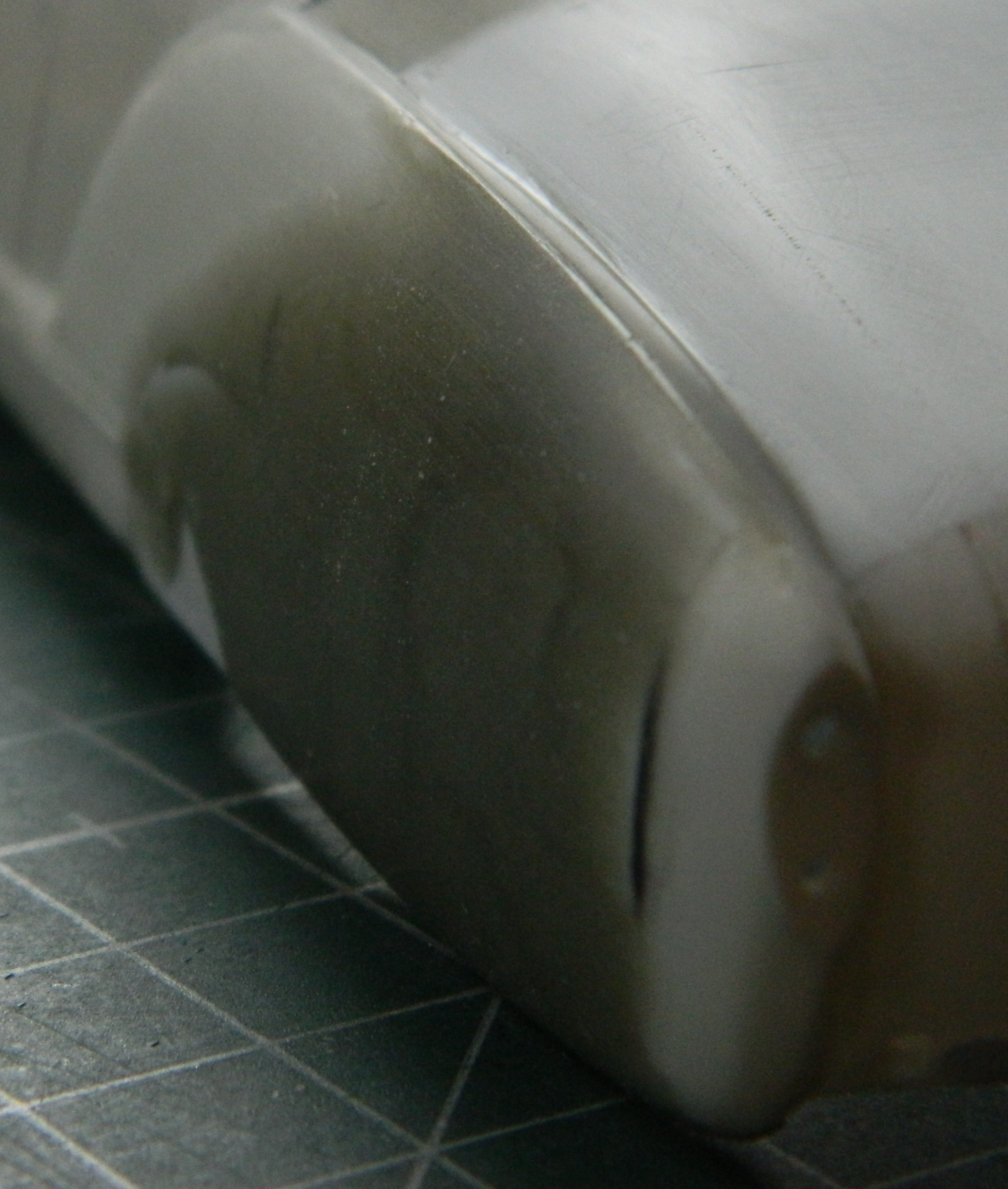

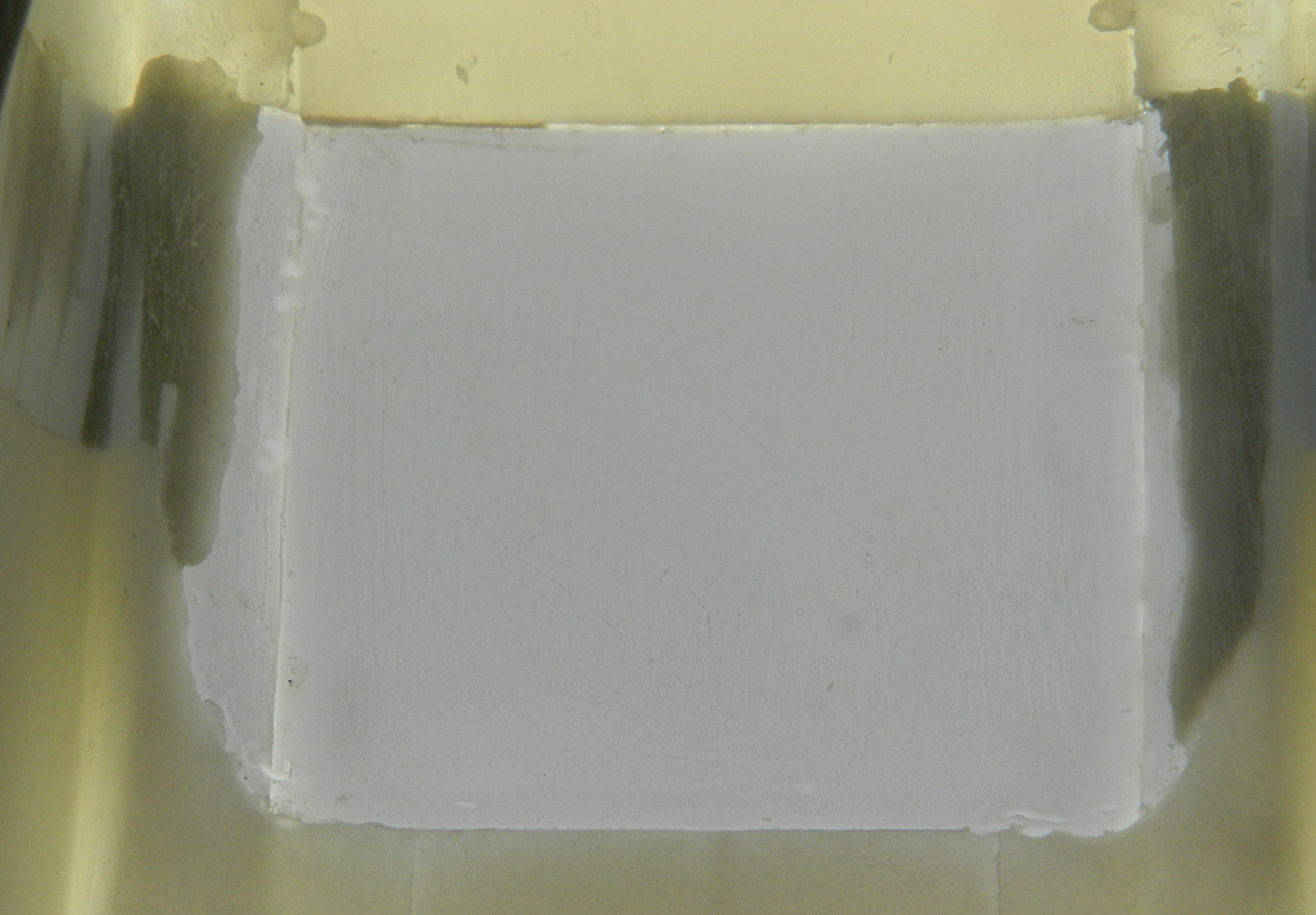

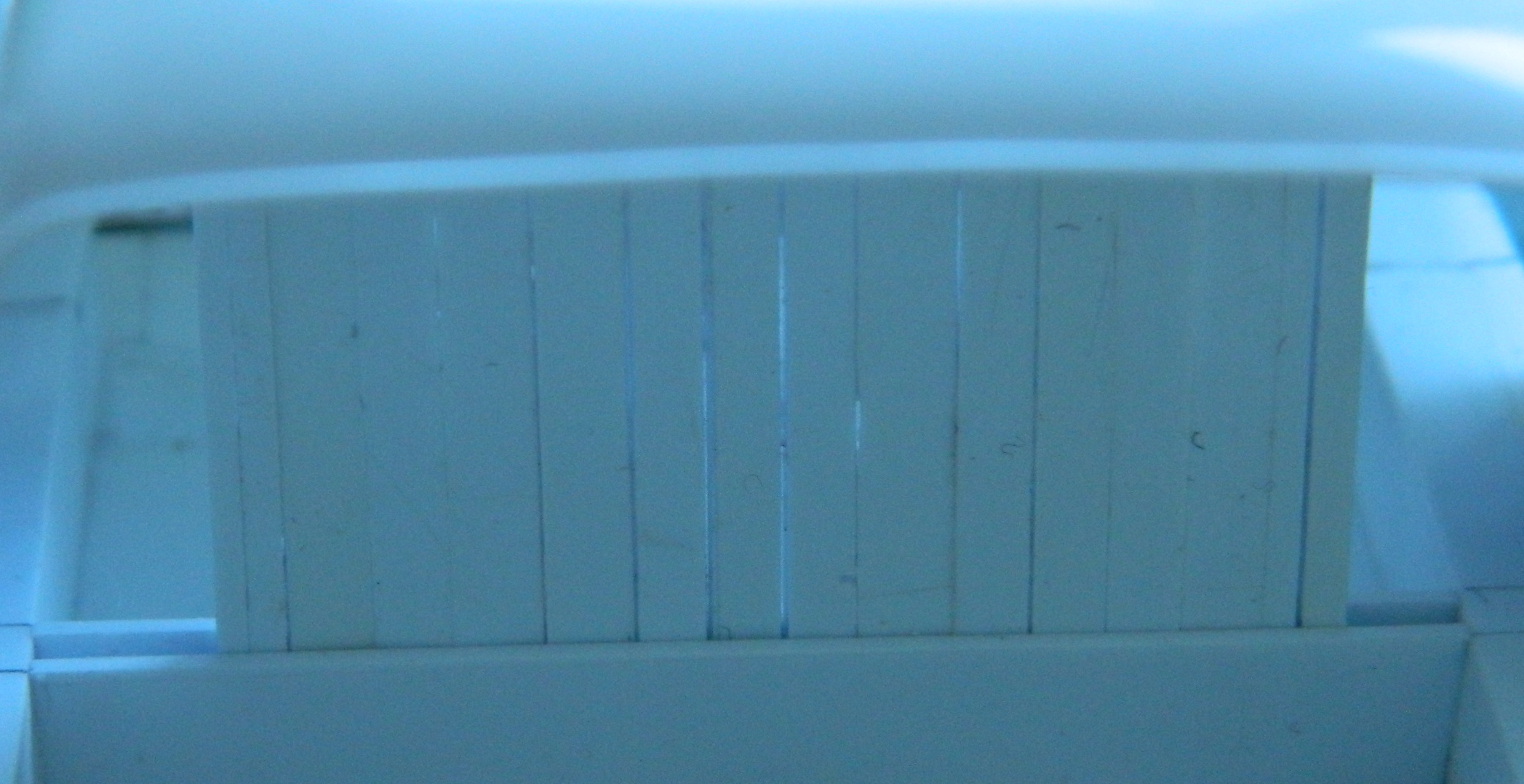

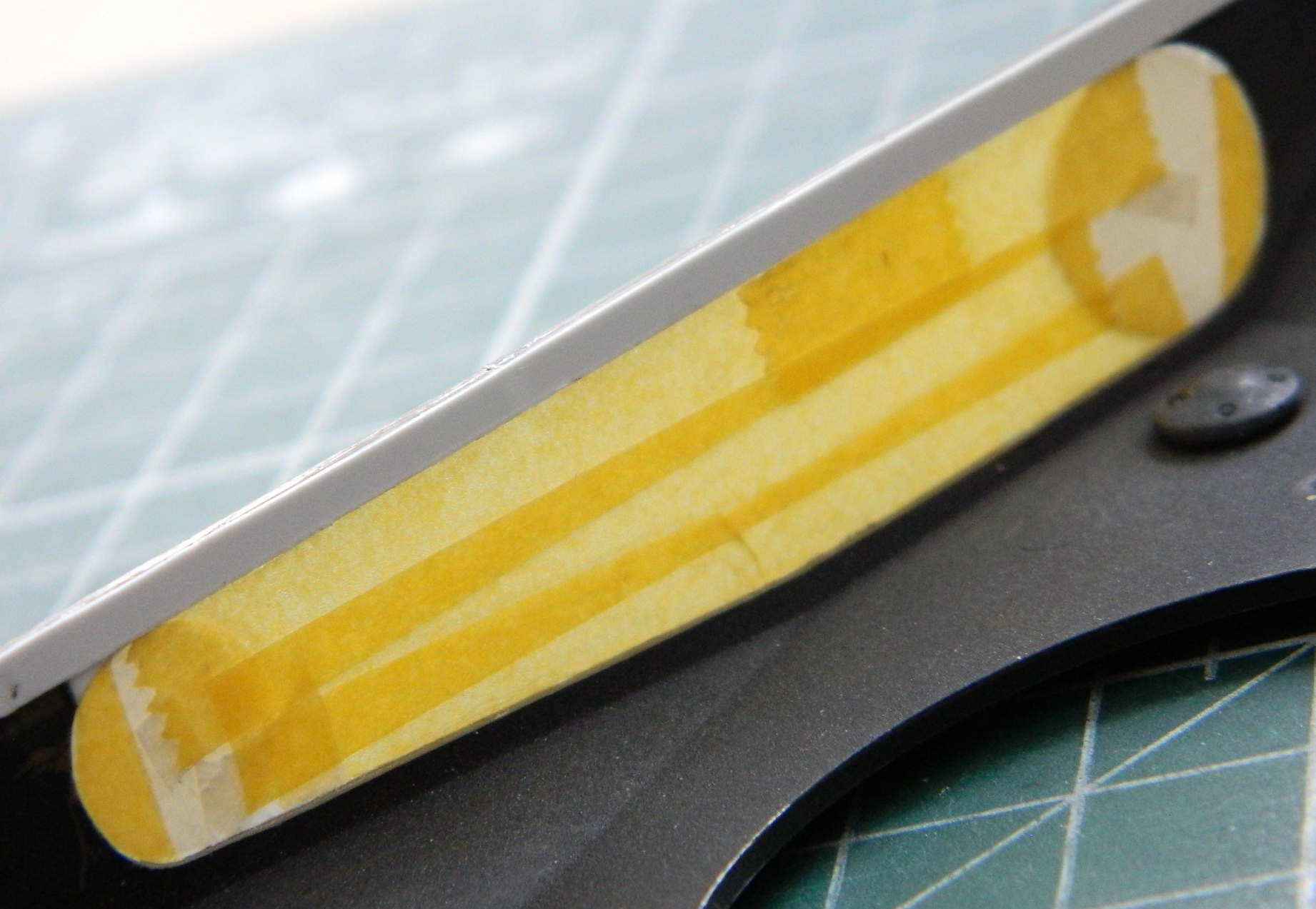

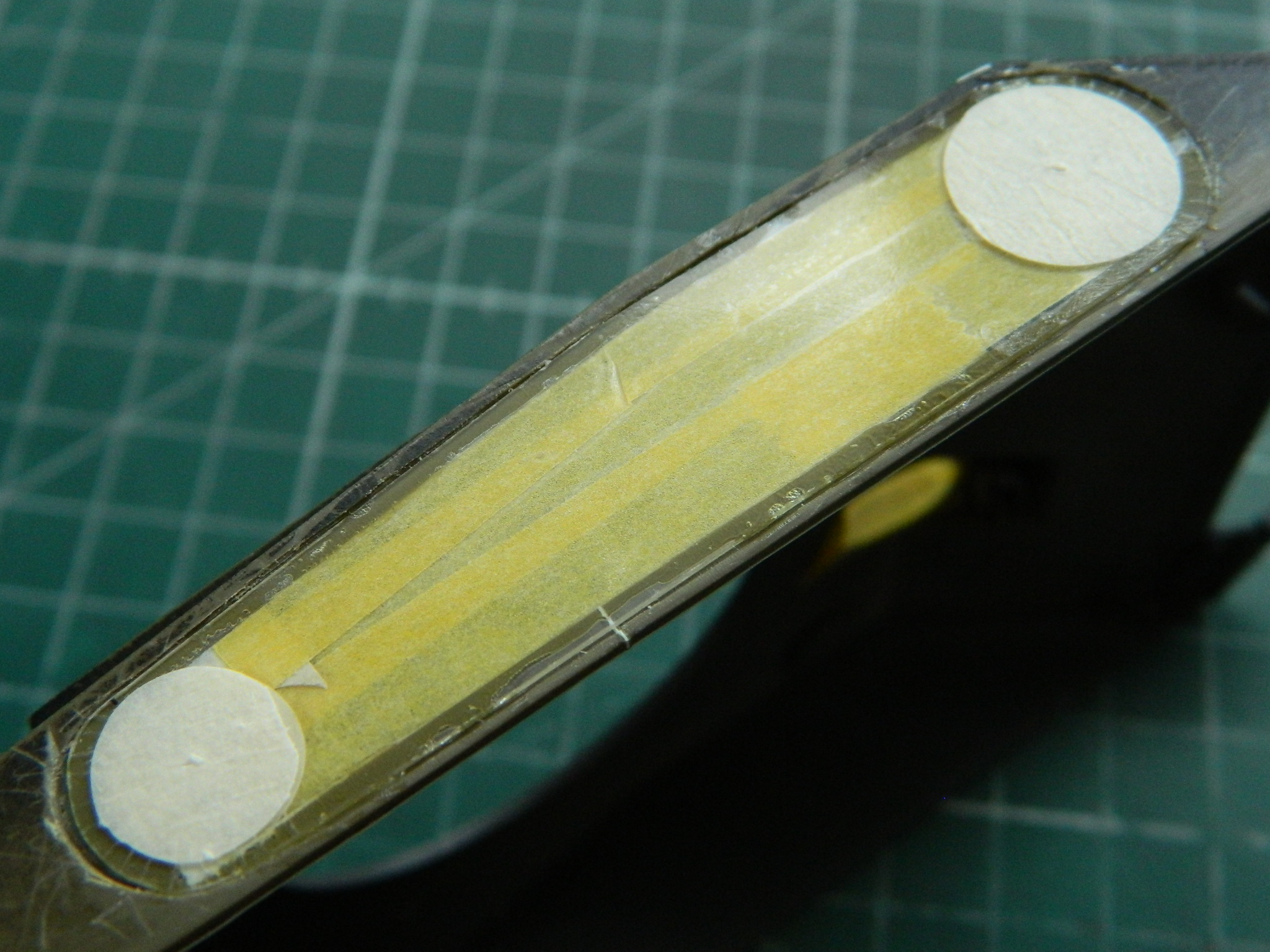

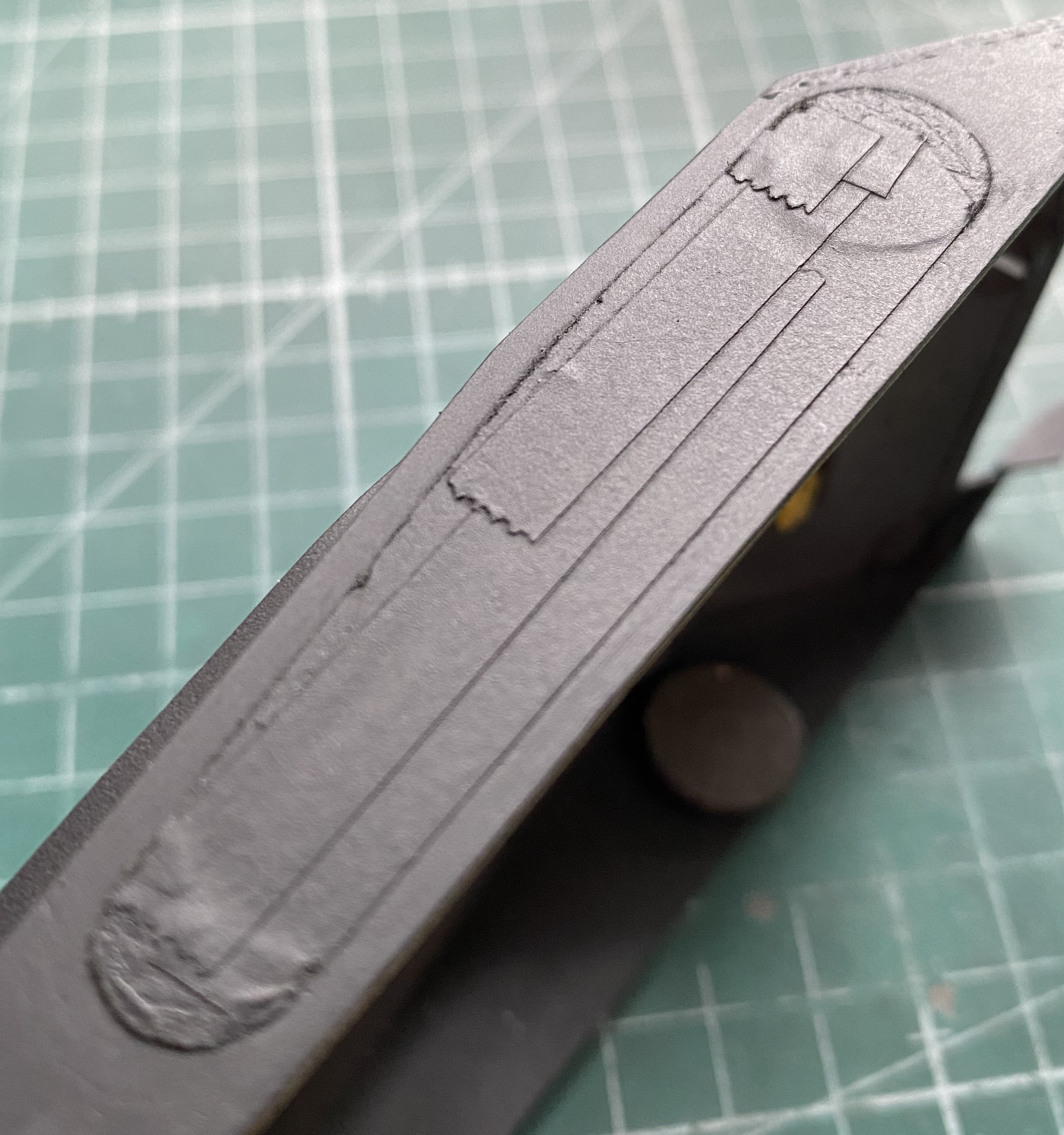

Firmly glued in, out came the flat black again to pre-shade everything:

Next month these will all be painted aluminum. Who knows…I might even do other things as well.

F7F-3 (AMT/Italeri) 1/48 Scale Build #3 –Continuing to Populate the Engine Nacelles Some More

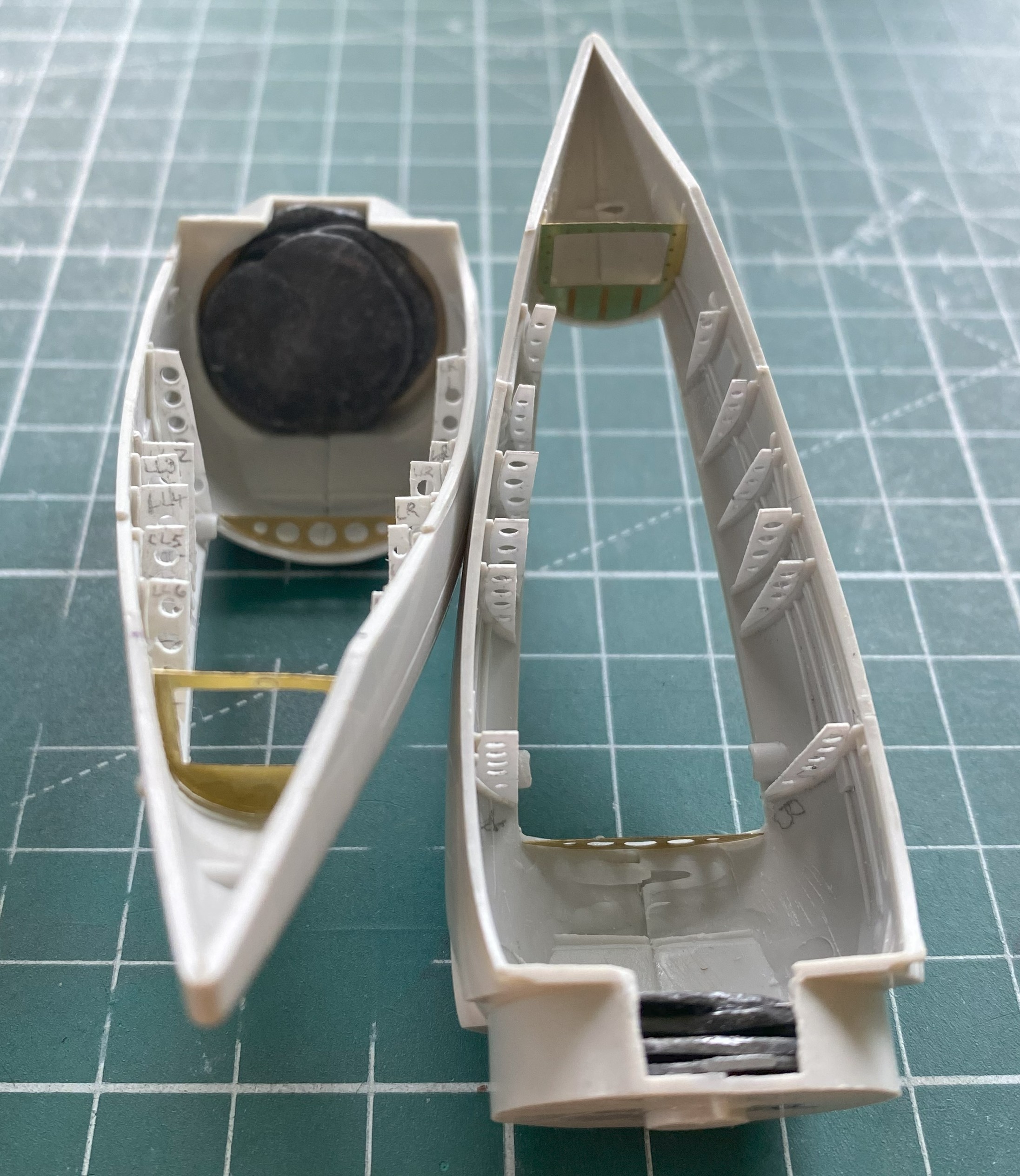

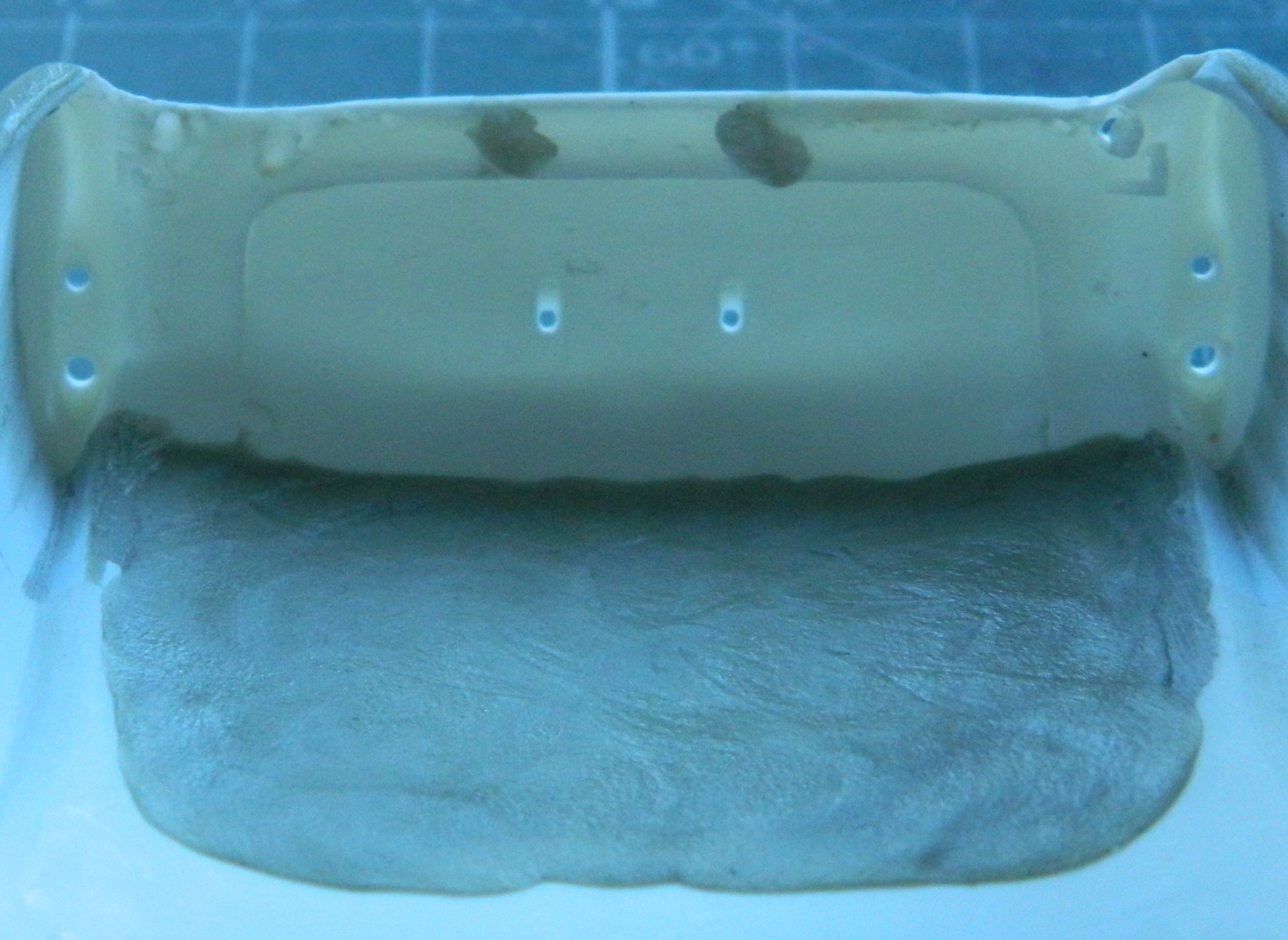

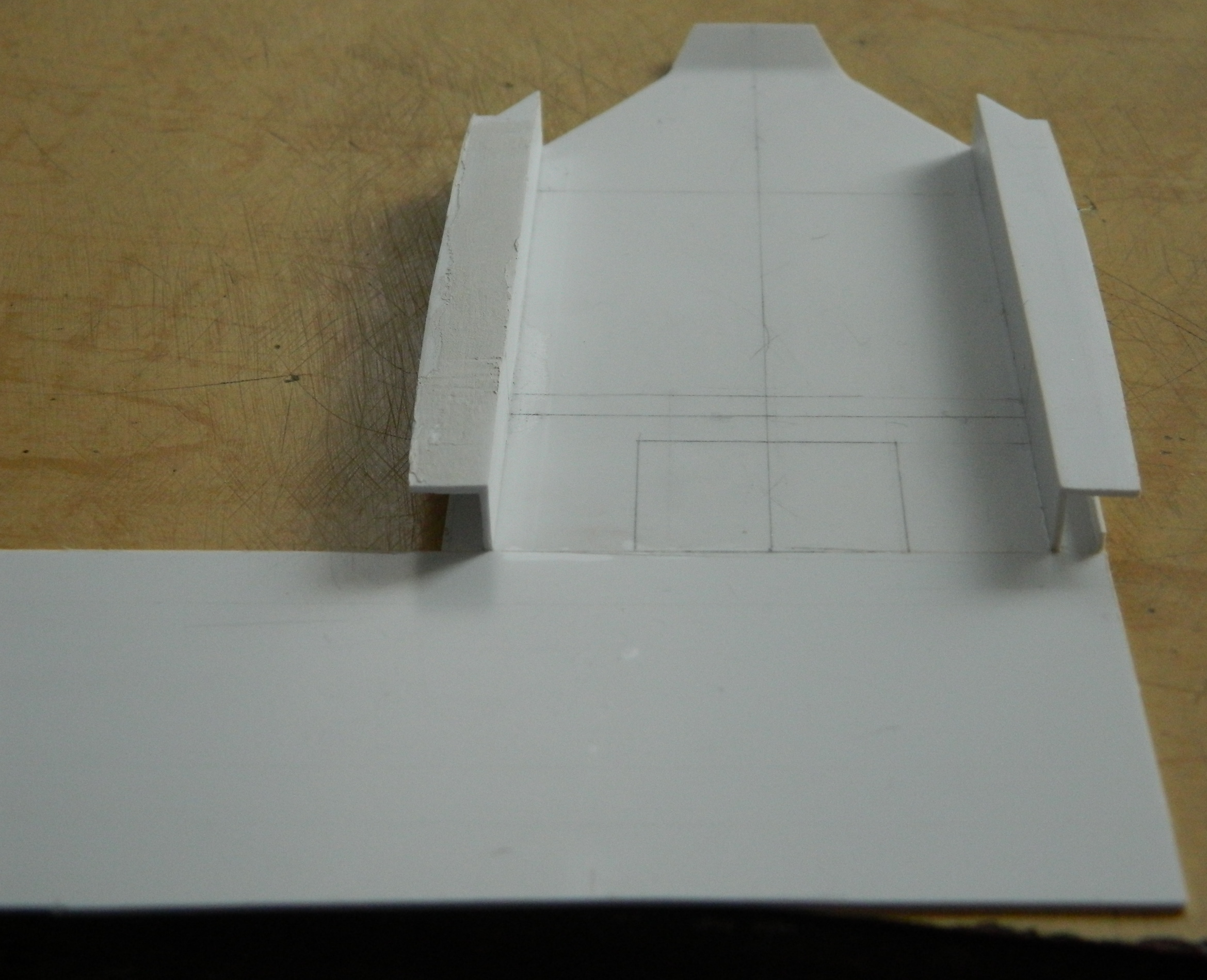

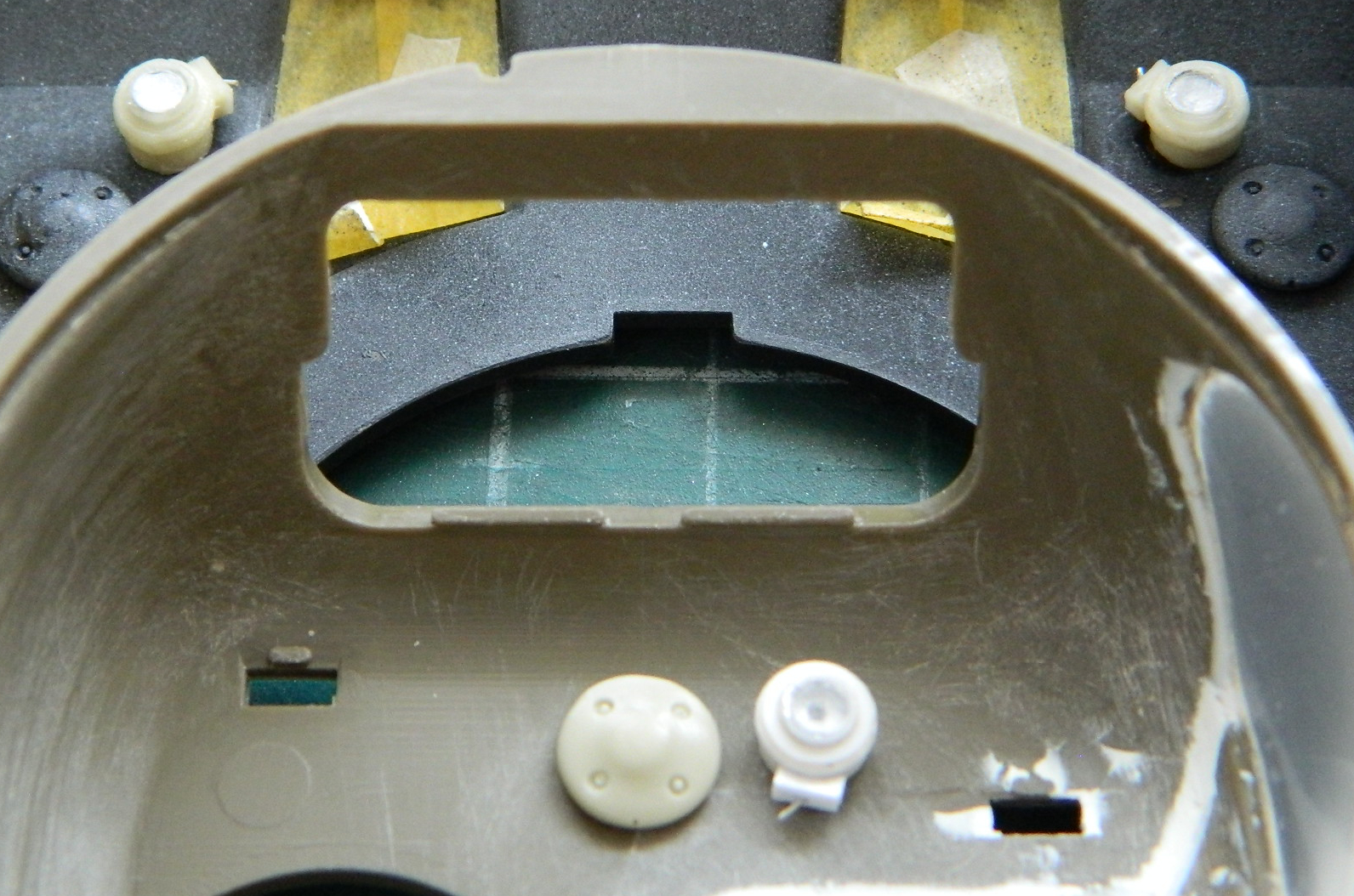

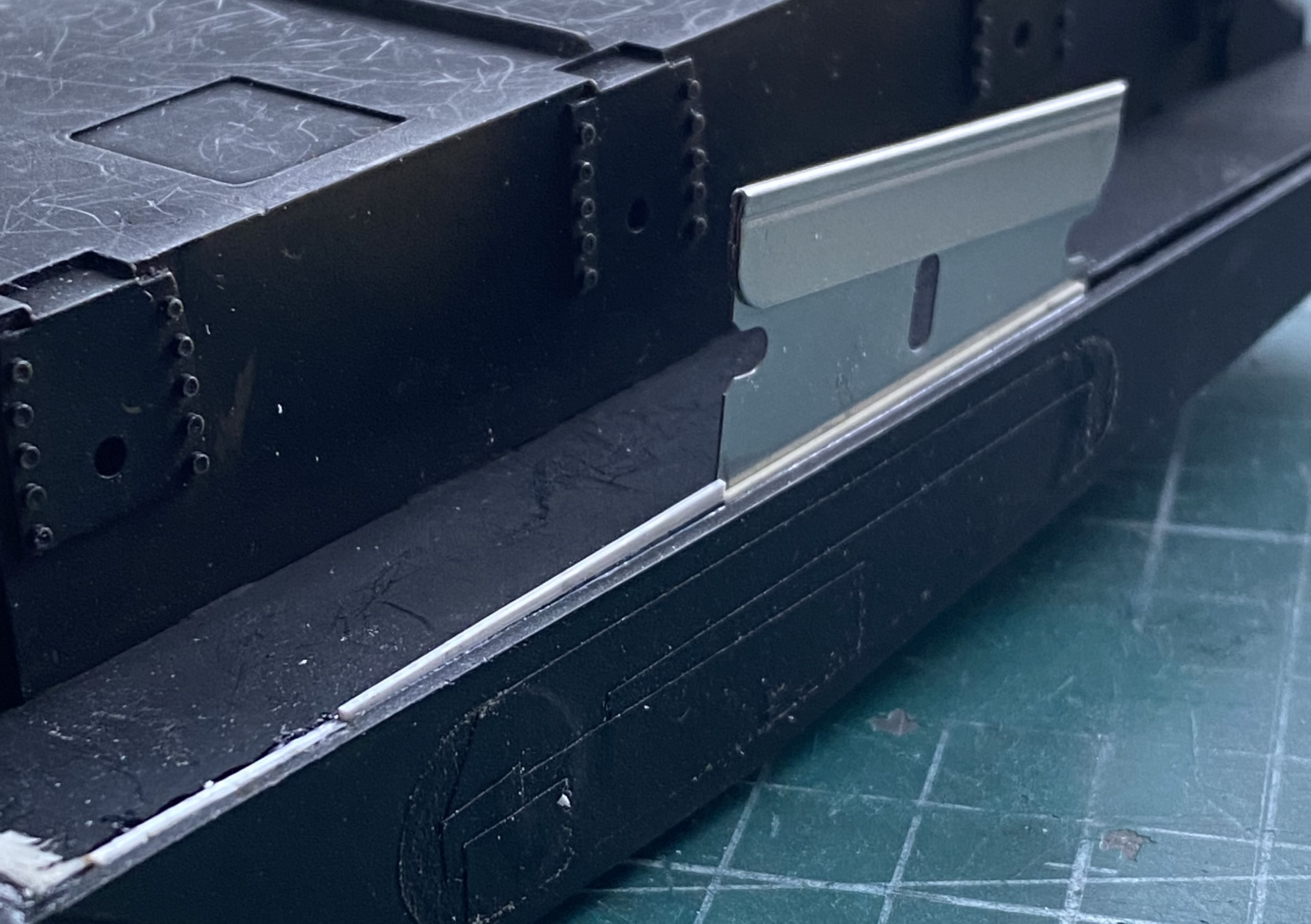

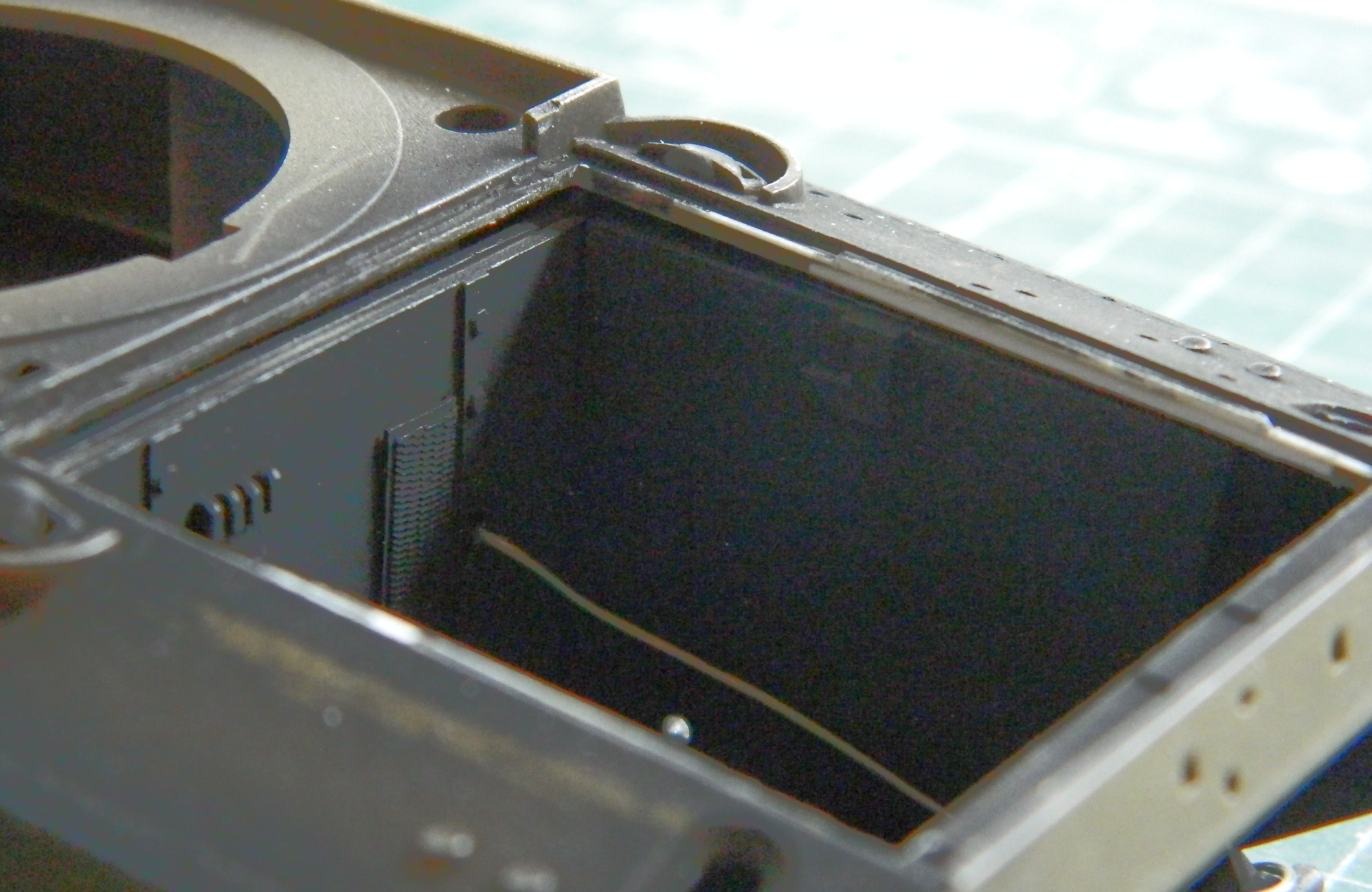

The landing gear bays with this kit are large, which I guess shouldn’t surprise me since this kite used a pair of the P/W R2800 which weren’t known for being small. Once upon a time, I would take the opportunity to detail the hell out of these bays as I did with the Blackbird build. And then I realized how infrequently the ‘Bird gets picked up and someone actually looks inside the landing gear bays. Not anymore. I’ve added some structure, the ribs and stringers, that could be seen, but I’m not adding hydraulic lines, cables, or wiring harnesses. The last update showed the ribs being built and installed, meaning this update will show the stringers.

The journey of a thousand mishaps begins with the first step and this is where I’d ended the previous update:

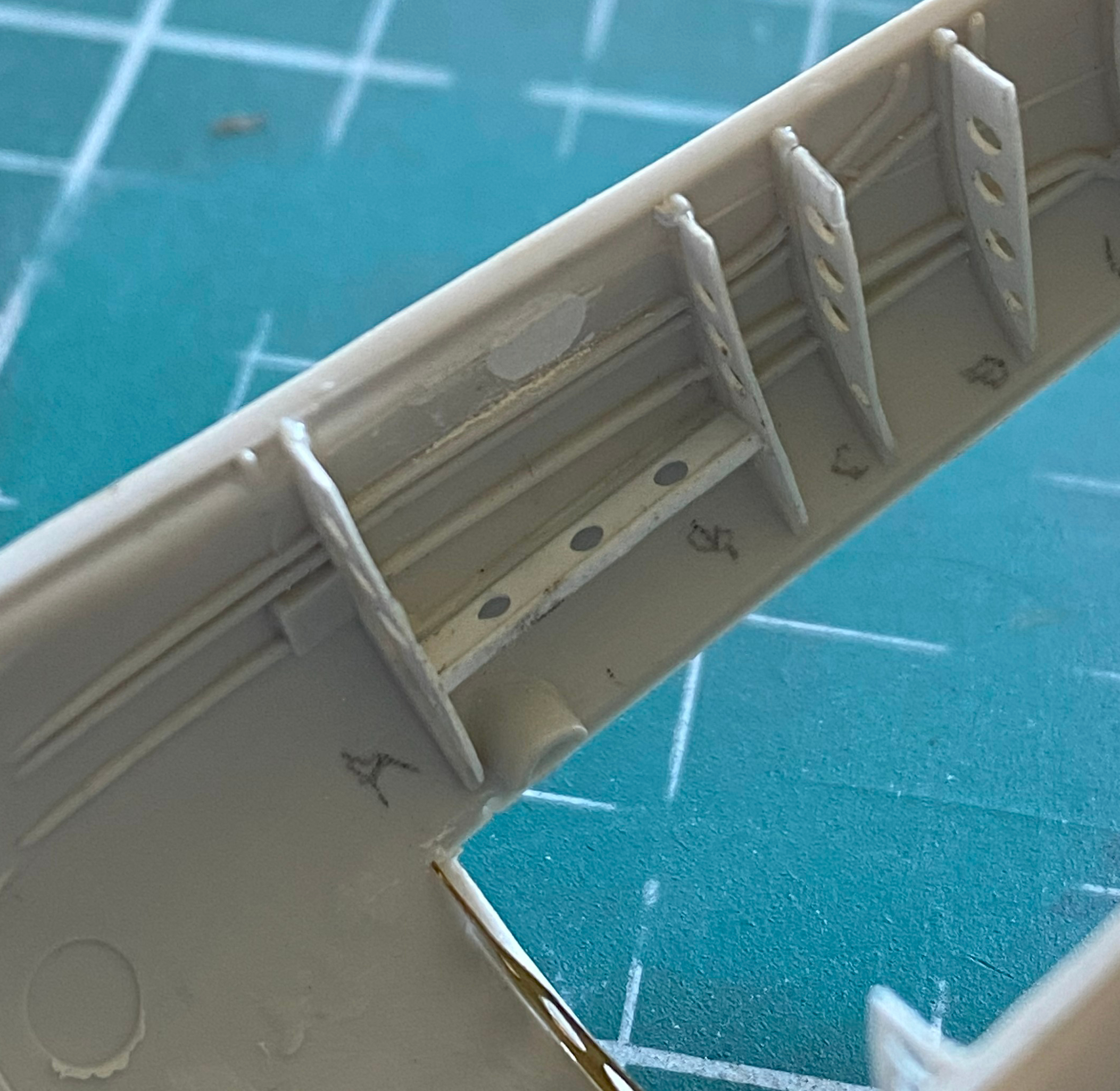

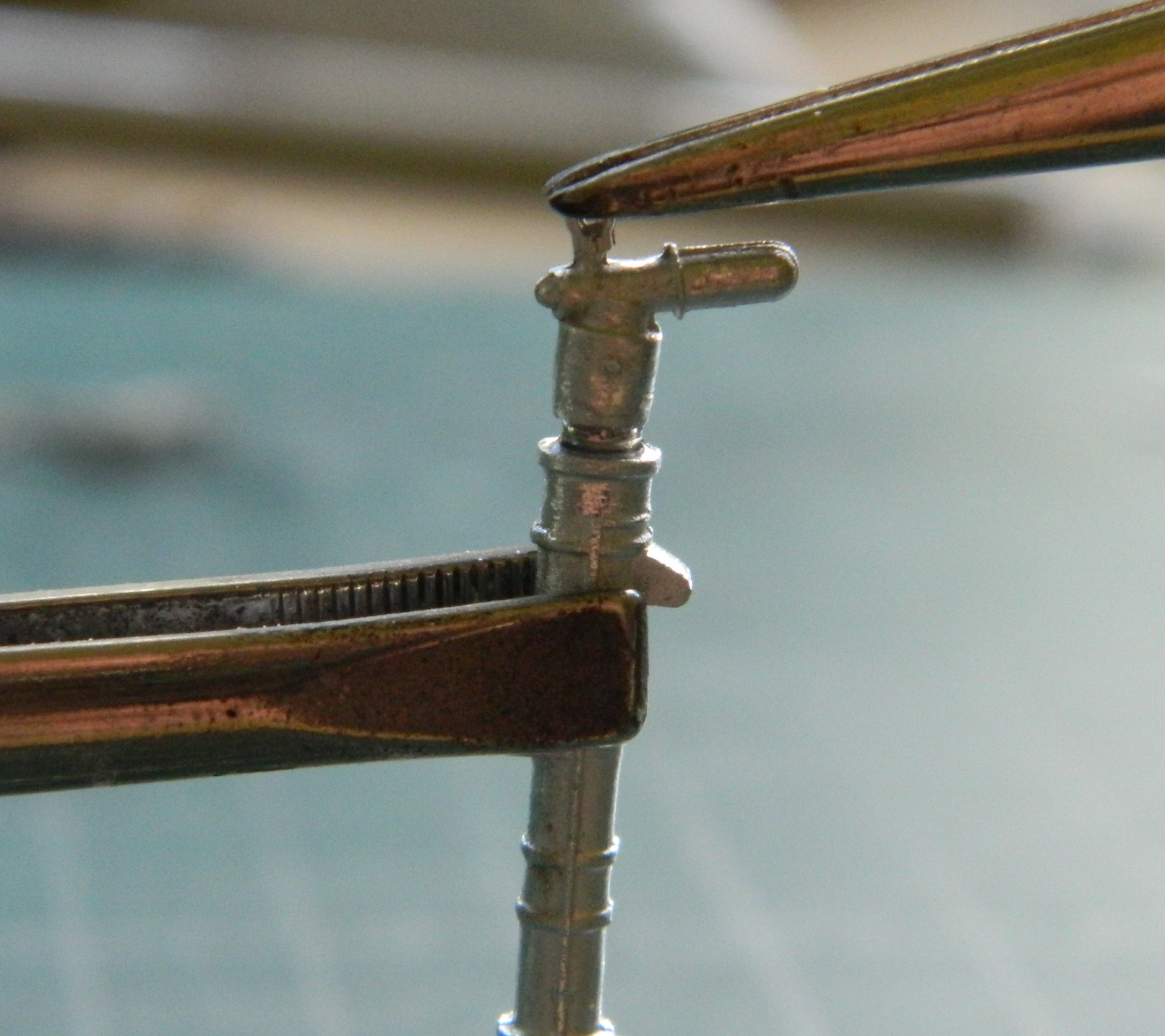

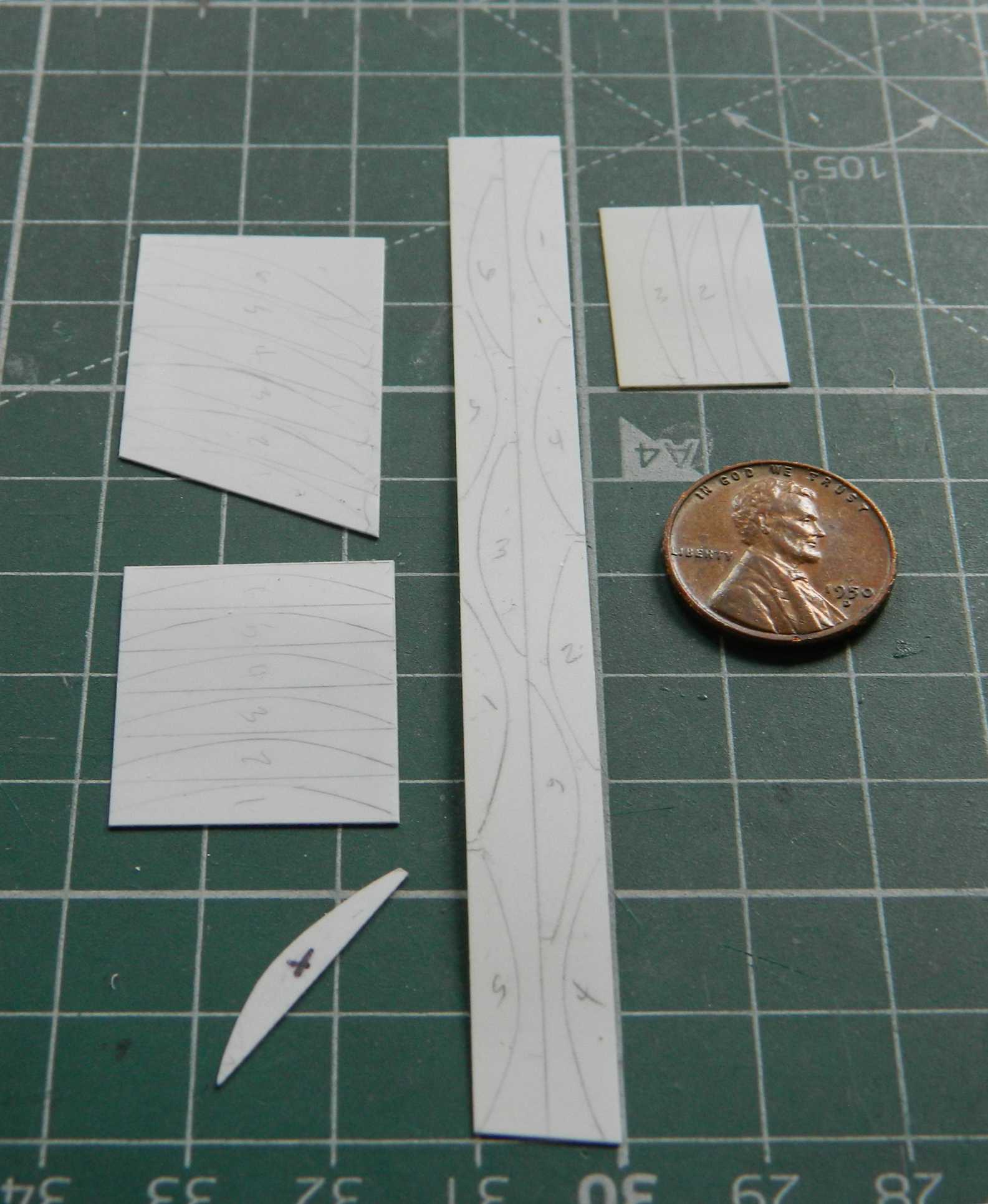

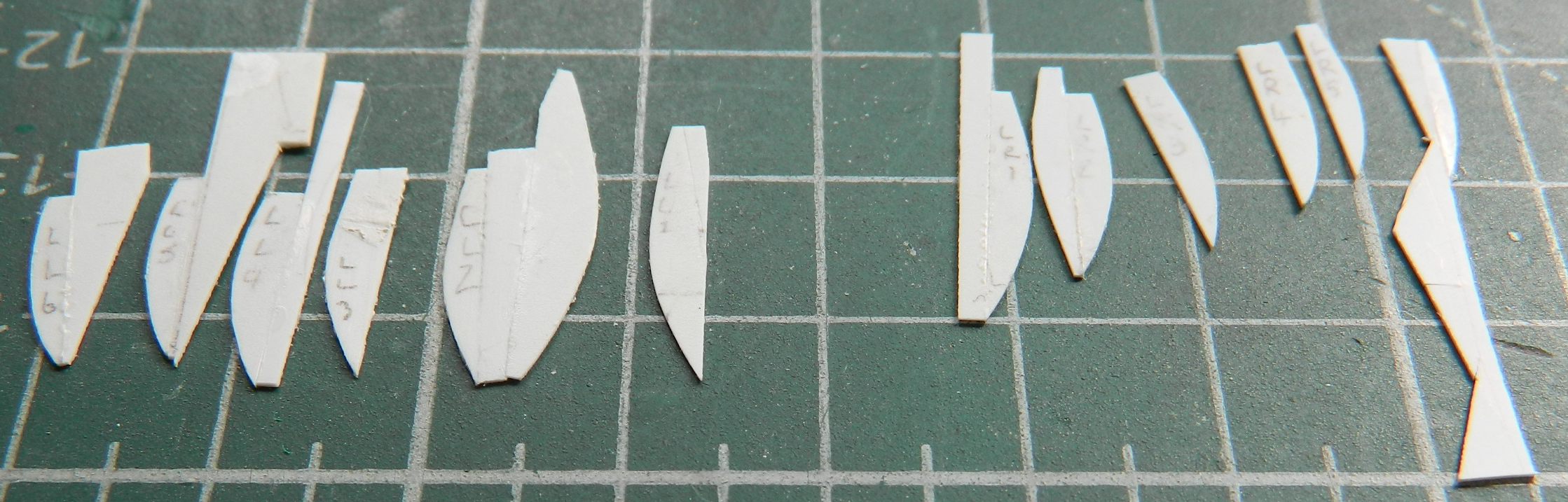

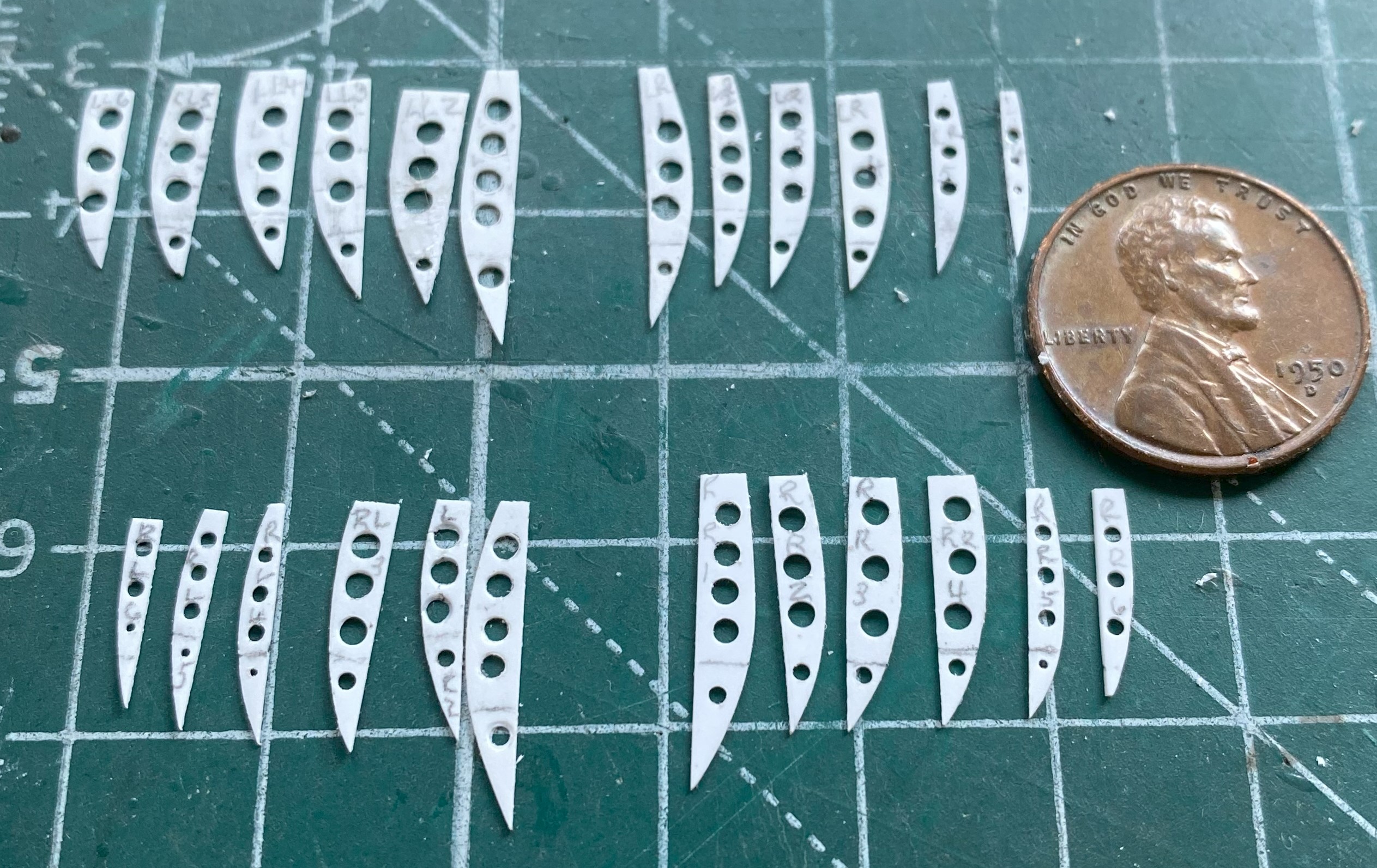

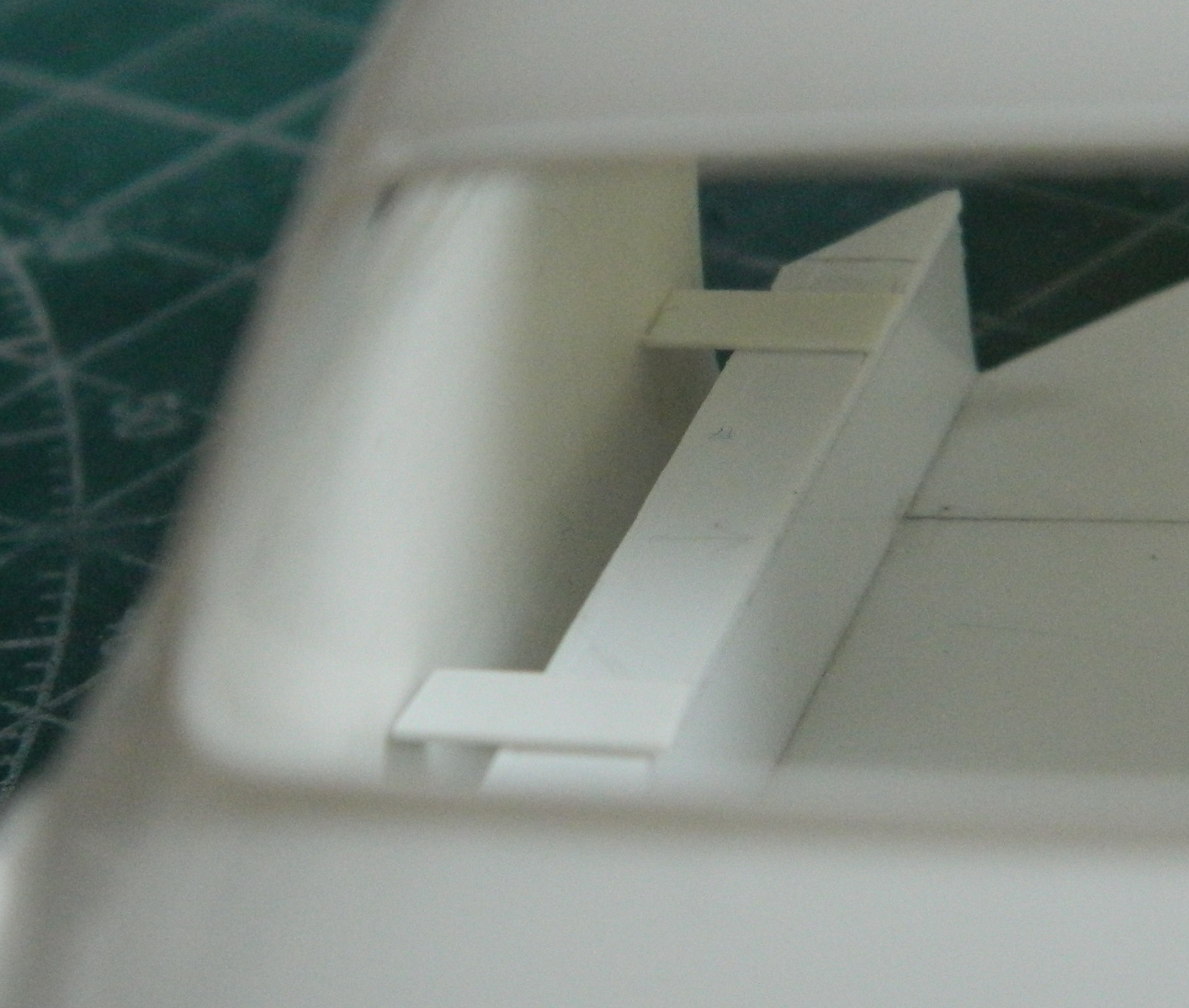

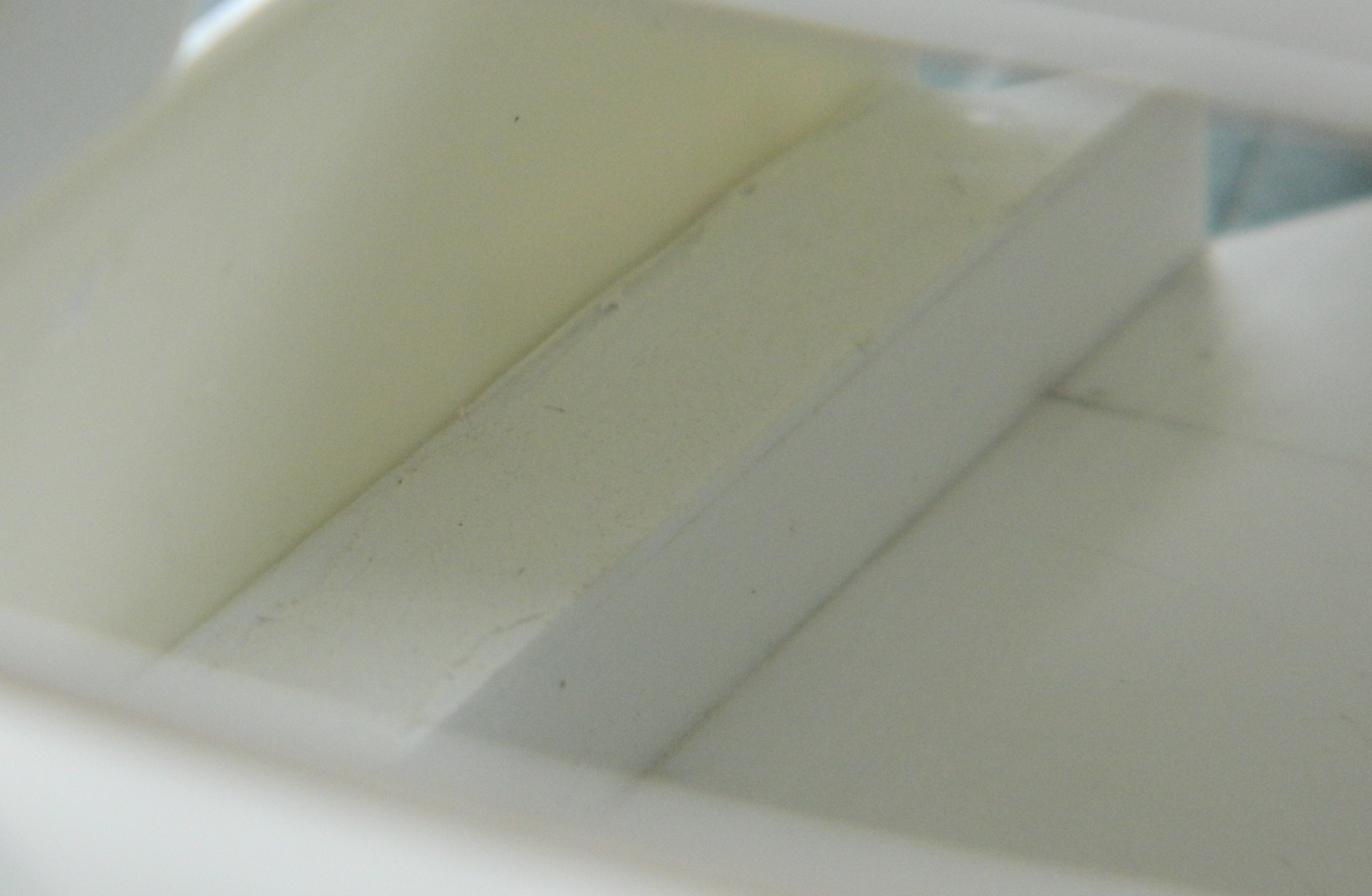

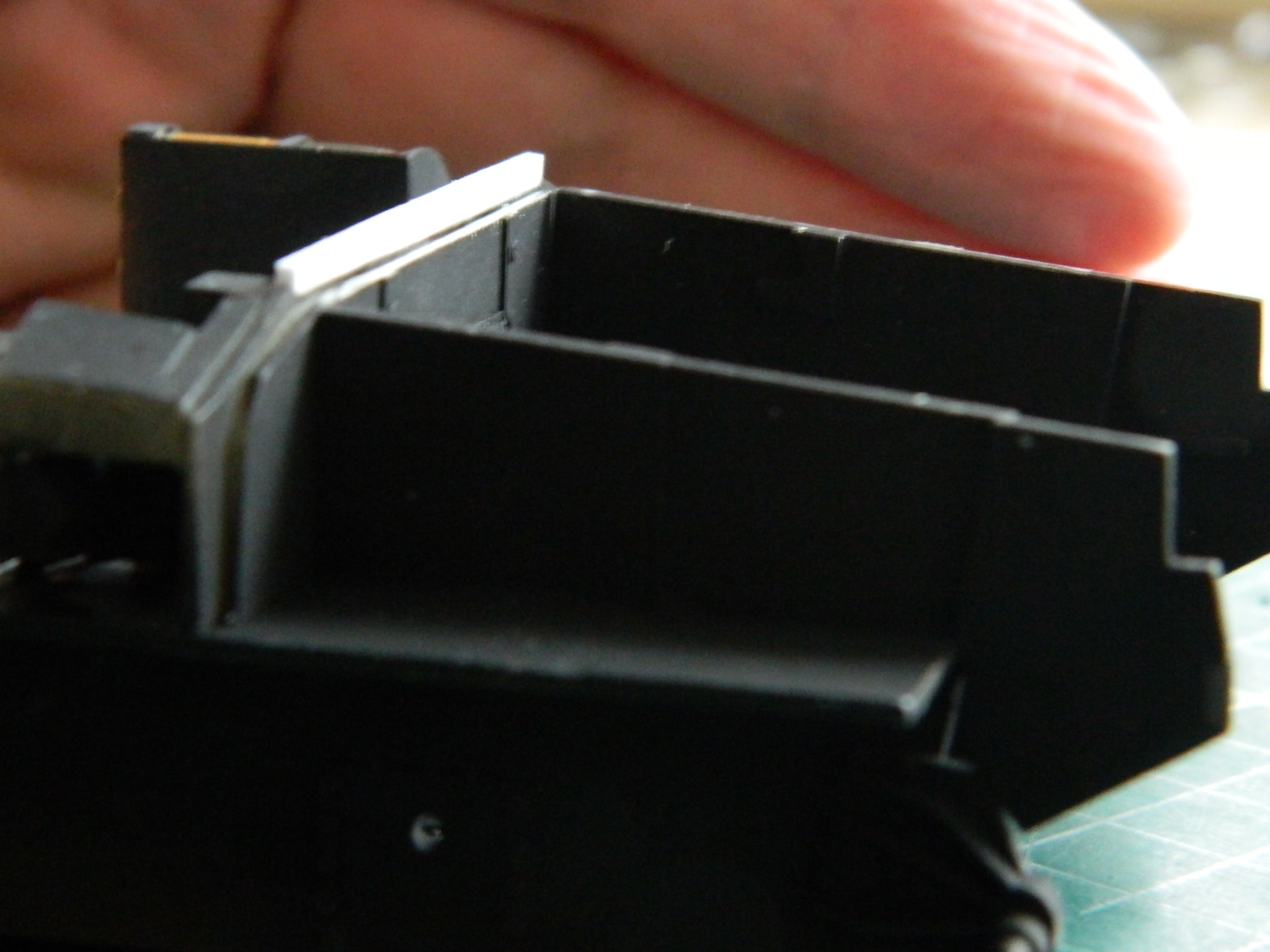

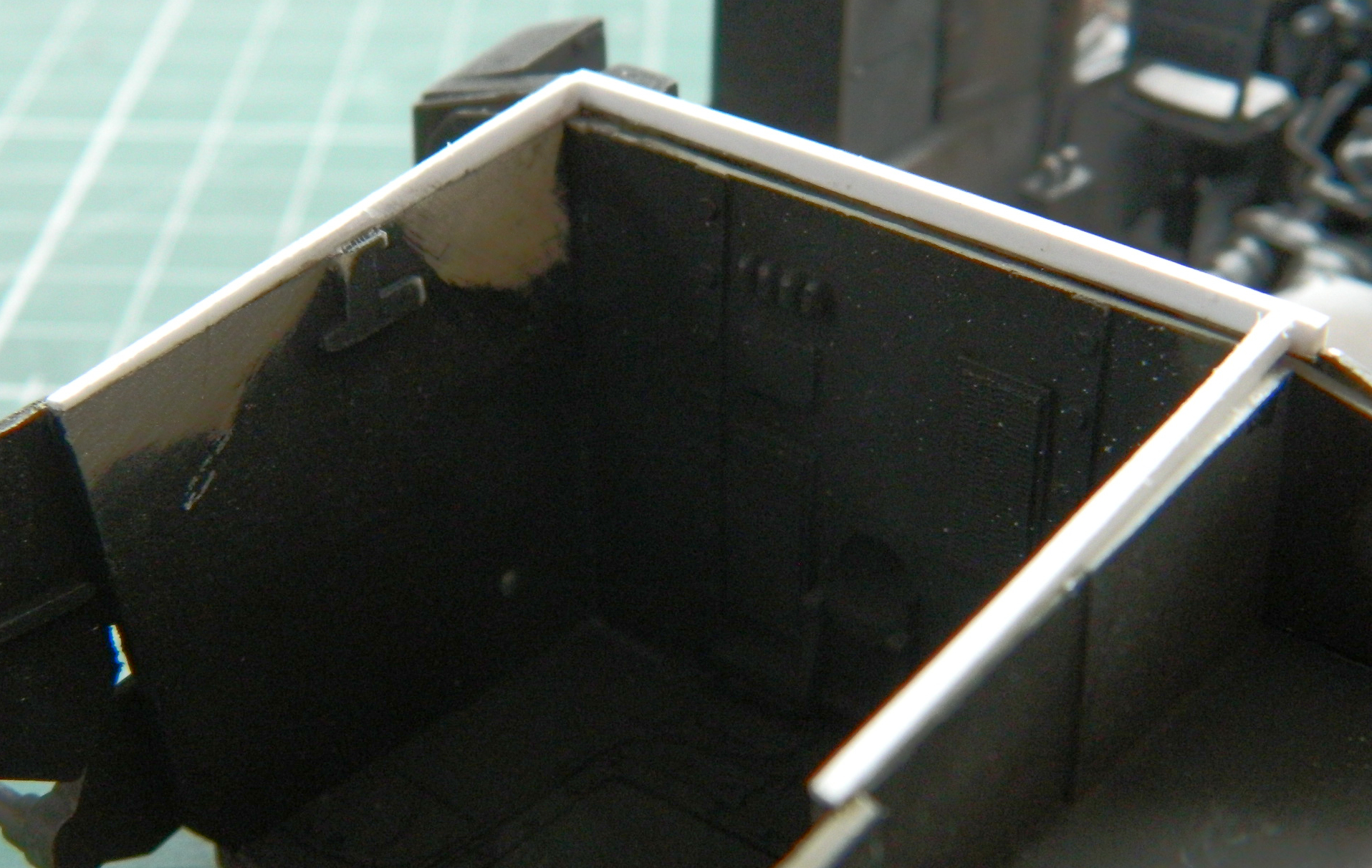

There isn’t a lot of photos in this update because of things like this, which is adding the lip that the stringers had (all 24 of them). Small details take time. I used 0.010″ (.254mm) for both the stringers and the lips. Once I had the approximate dimensions, essentially the length and width, the lips got added before the absoLUTE joy of fitting all these things in:

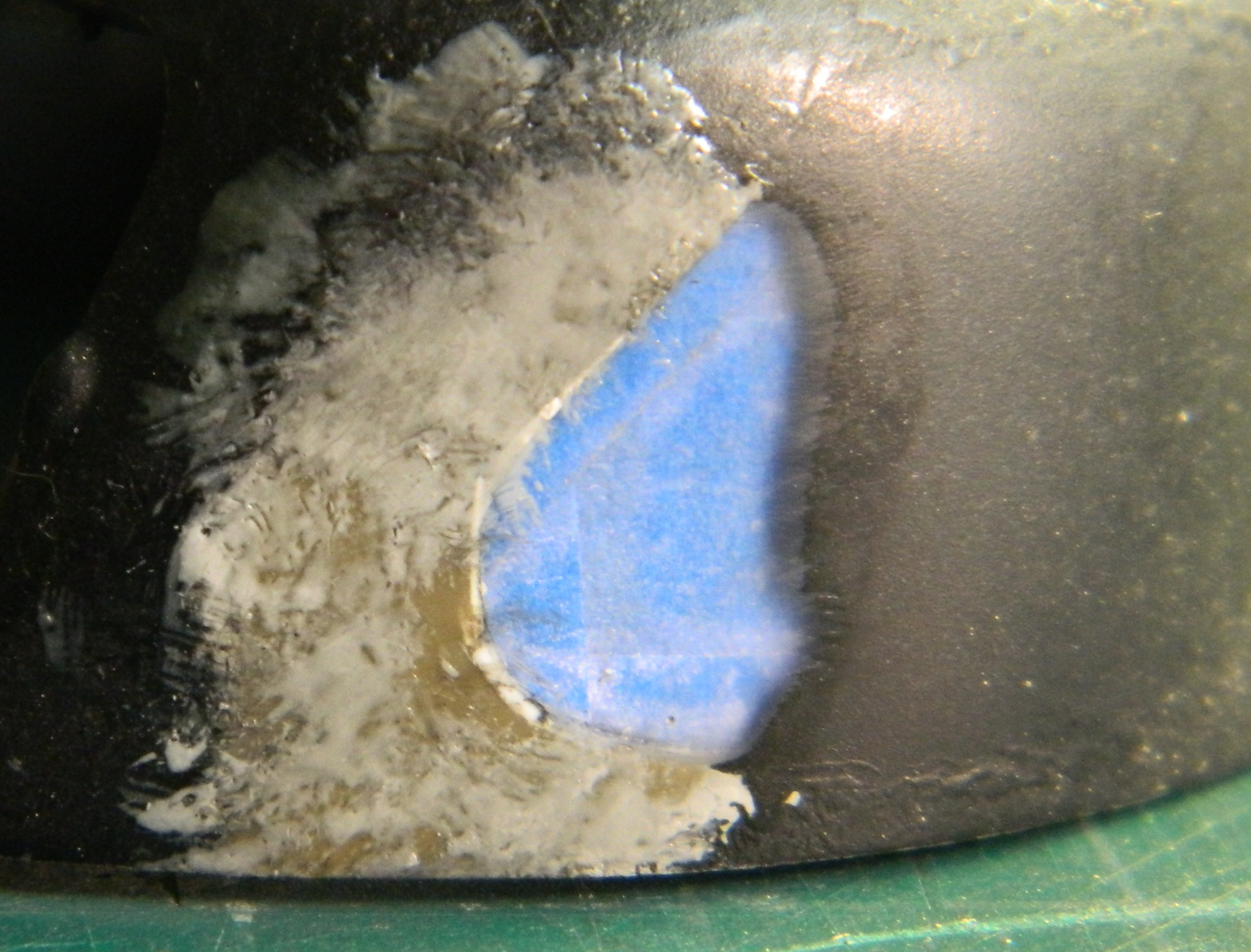

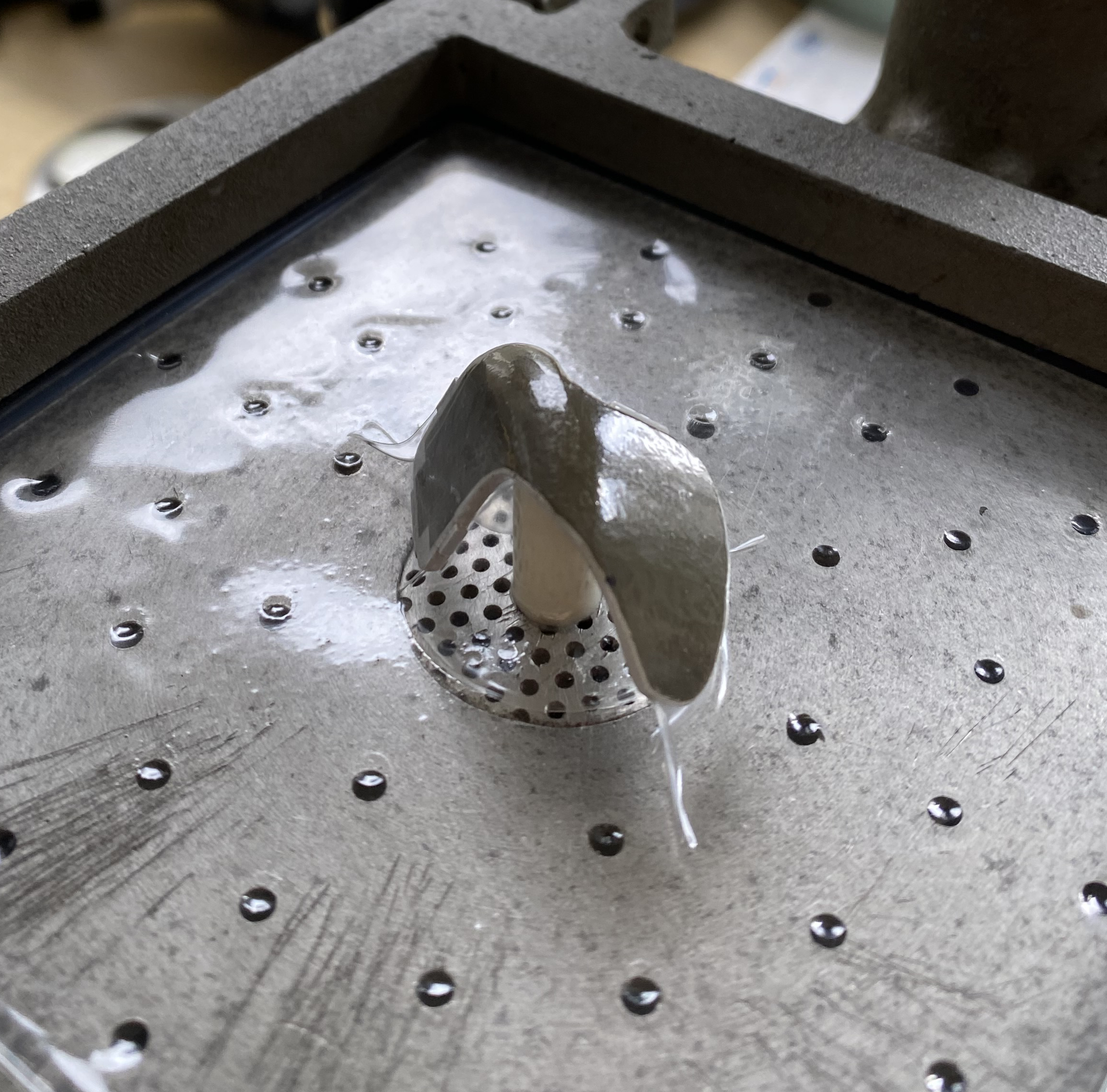

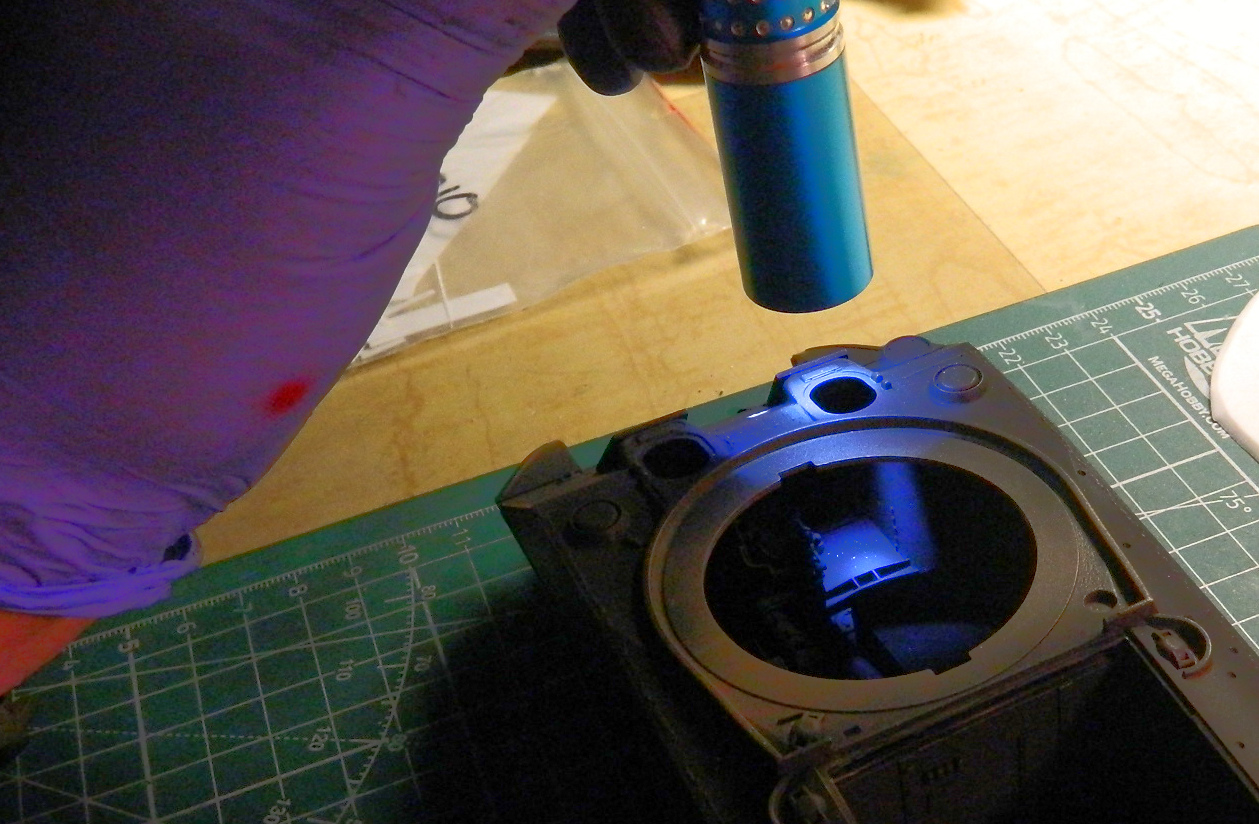

Now that I have a new tool to play with, specifically UV-setting resin, I used it more and more during this phase of the build and my conclusion is that this stuff is DEFINITELY useful. When dealing with a new item, I always read the directions. The directions of this stuff tells me that I can’t rely on natural sunlight to cure it. Well… I used the provided UV light to cure the resin and that works well, sort of like superglue with plenty of time to get the parts correctly positioned. And like how I use superglue, I put a small drop of the resin on my worktable and added it to the model using needles and dental tools. What I did notice, however, is that the resin will end up being cured somewhat by just sunlight. This is what happened after about five minutes of exposure to direct sunlight:

I’m pretty sure I’ve mentioned in other places in this site that I’m parsimonious. And I’m also a cheap bastid. Wasting product, any product, is right near the top of my must-avoid list. So since sunlight will cause partial curing, which is wasteful of product, I took a piece of cardboard scrap and fashioned a sun-shield with it:

Though the drop of resin will still cure on the table, that rate of curing is substantially slowed. Best I can do so that’s good enough.

So I made a lot more stringers and lips:

I discovered quickly that I can forget which side of which nacelle any given part is intended for. To counteract that, as I made a stringer, I trimmed, fitted, and glued it in place using the UV-setting resin:

I just kept plugging away at it until I got both nacelles done:

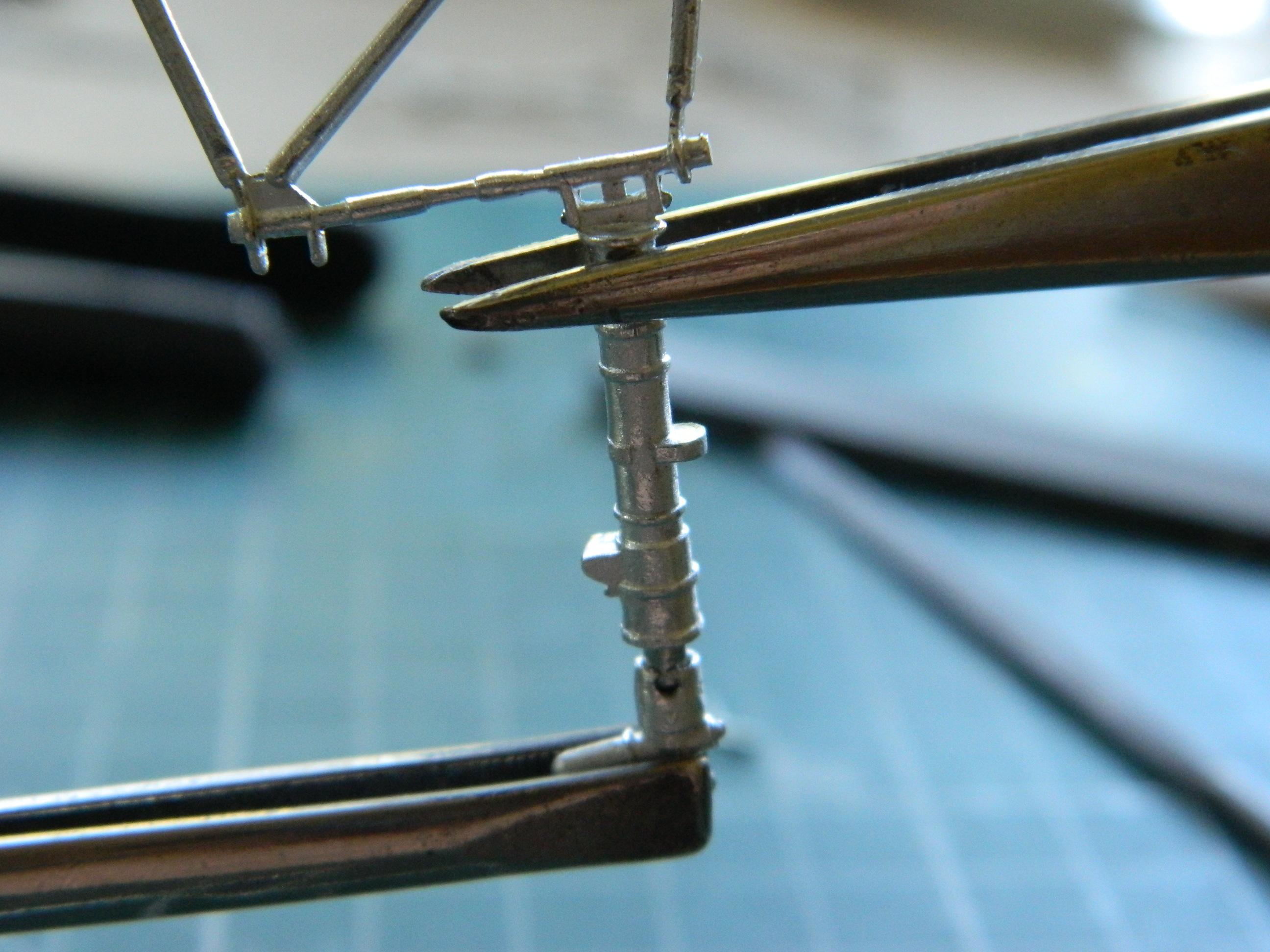

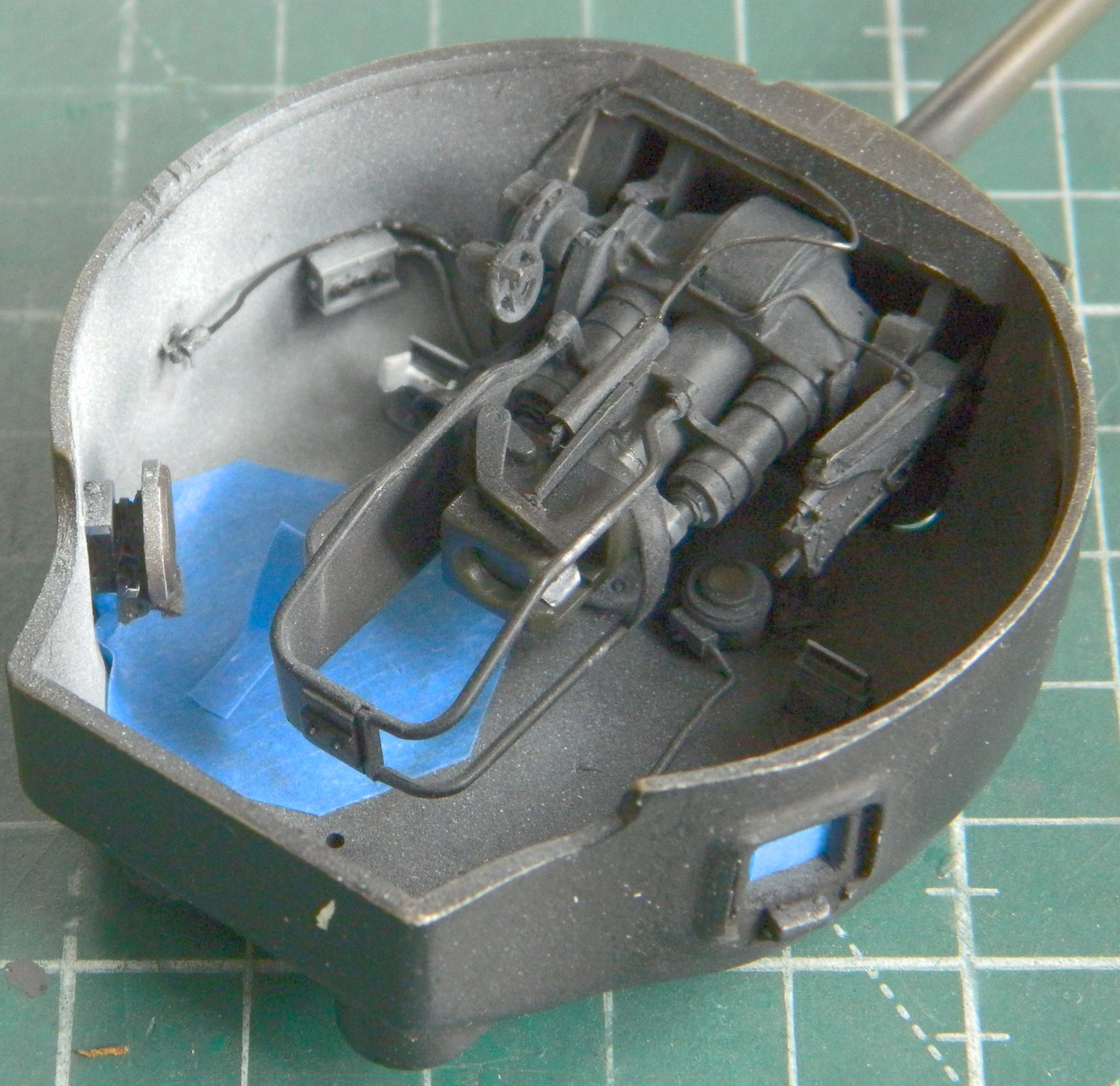

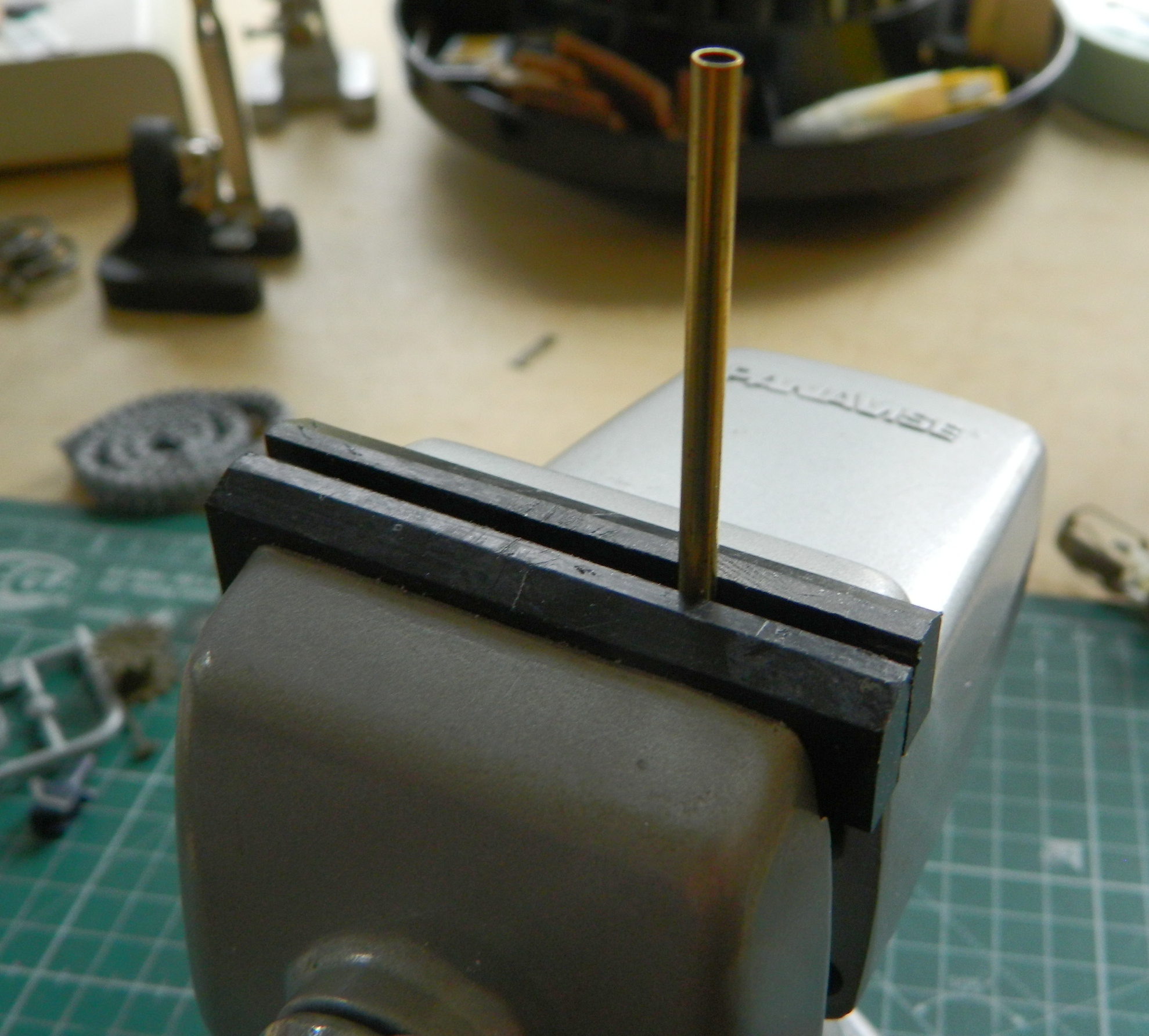

With the ribs and stringers done as much as I’m going to do them, it’s time to fit the landing gear leg assemblies into place…and that took a bit of doing to accomplish. I used the kit’s plastic struts as my gauge because the SAC metal legs are direct copies of the kit parts. I learned a couple of things during this process. The first being that to save myself major hassle, I’m going to break from my usual process of waiting to add the landing gear until late in the build (less chance of breaking them, obviously). When I tried feeding the struts into place through the opening at the bottom of the nacelle I quickly understood what a pain in the ass this would be if I added them after the nacelles were glued to the wings. This time I’ll be adding the struts before the nacelle is glued (and puttied, because dry-fitting showed me that it’s needed) because fitting them into their proper places is SO MUCH easier when going at that task from the much wider top of the nacelles. The second thing I learned is that the ribs in front of the openings are too wide. The brace arms of the strut are in sufficient enough contact with the front ribs to bend those struts (the struts that are being bent are the ones in contact with the ribs on either side of them):

This photo shows how far away the struts are from where they’re supposed to be mounted:

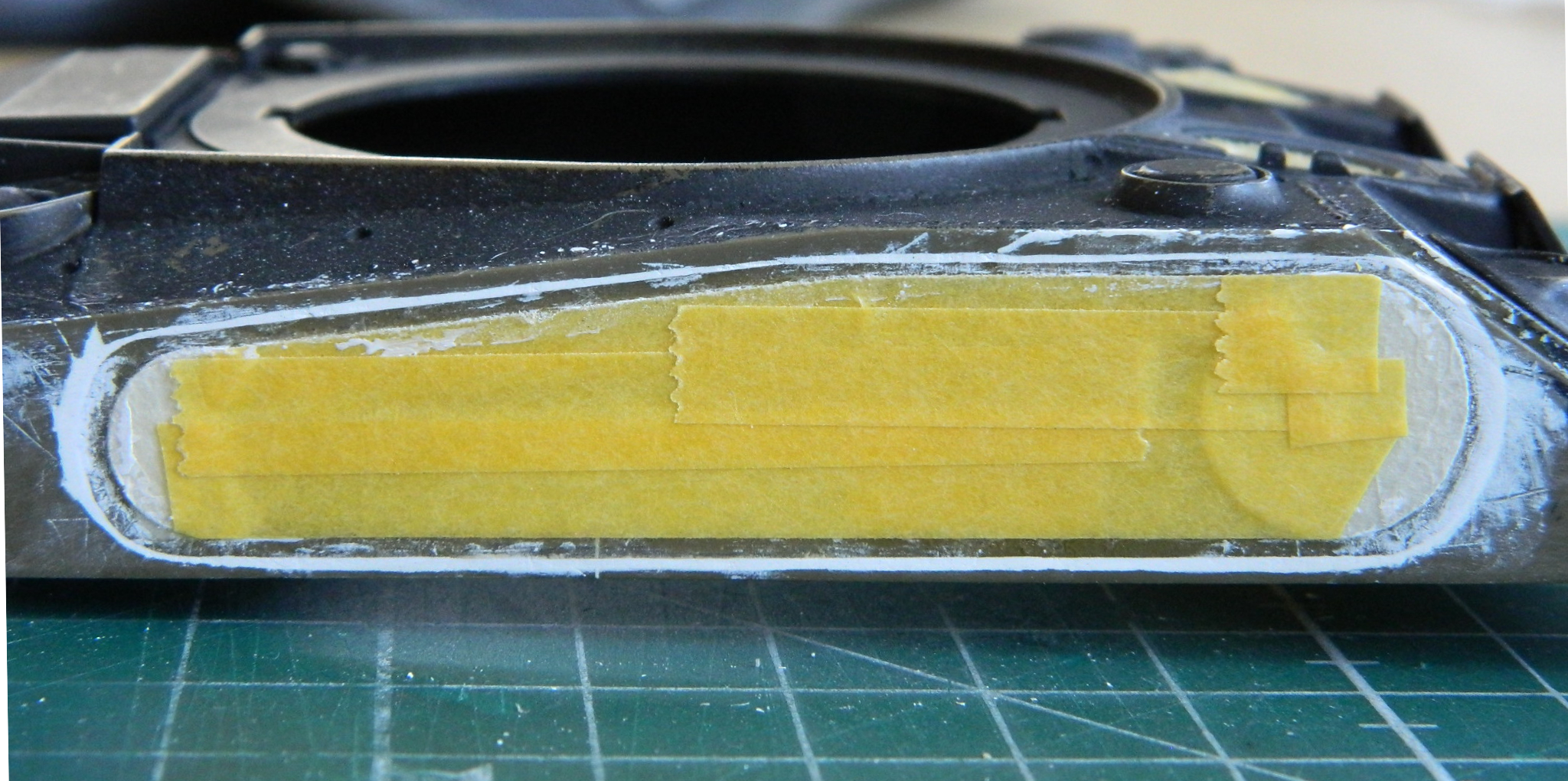

I like emery boards for jobs like this. Good abrasive, stiff, and can easily be shaped to fit the task at hand. Here I’d split the emery board lengthwise and then snipped the rounded ends off (using wire cutters), something I could also do as the abrasives wore away:

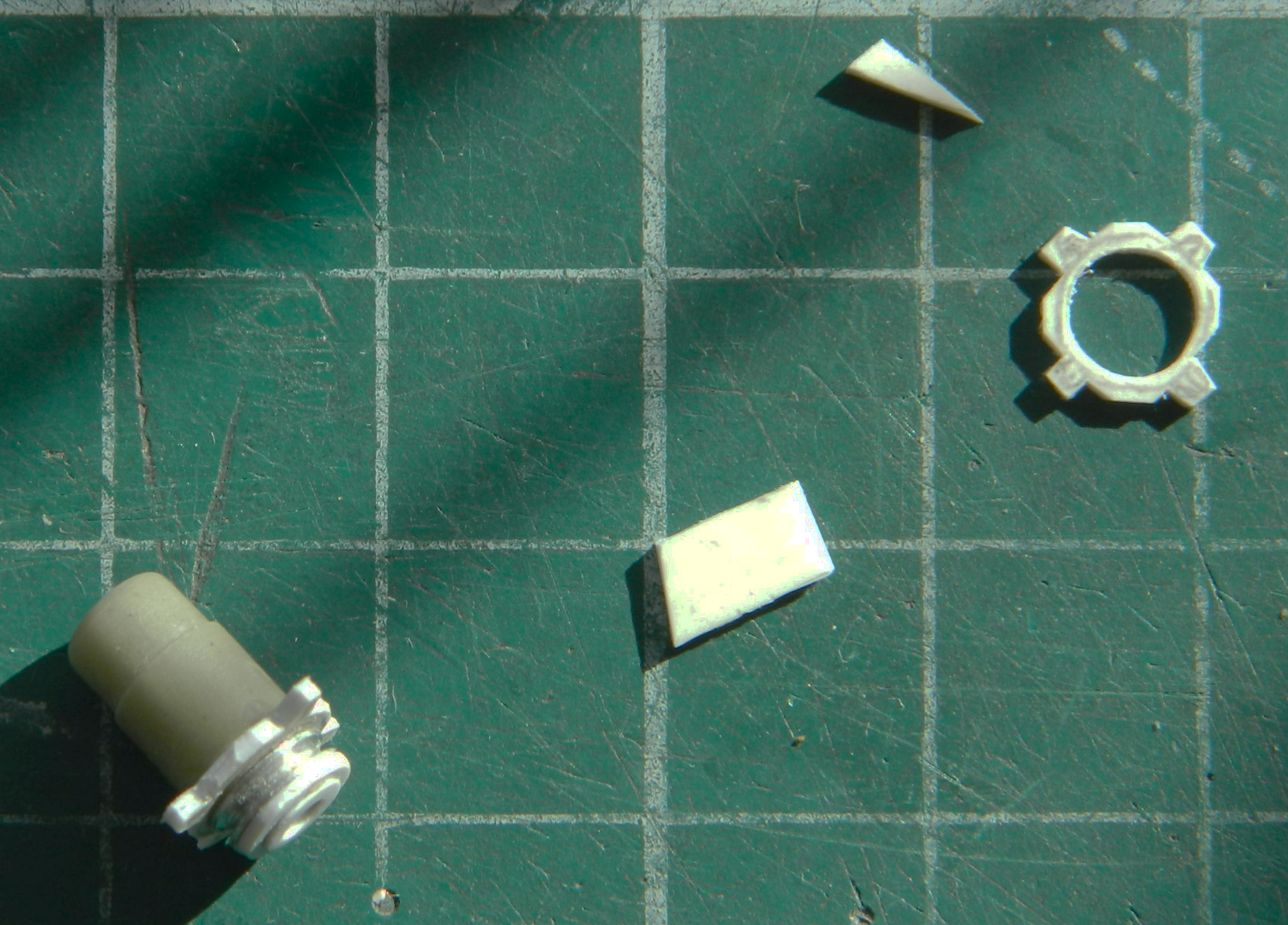

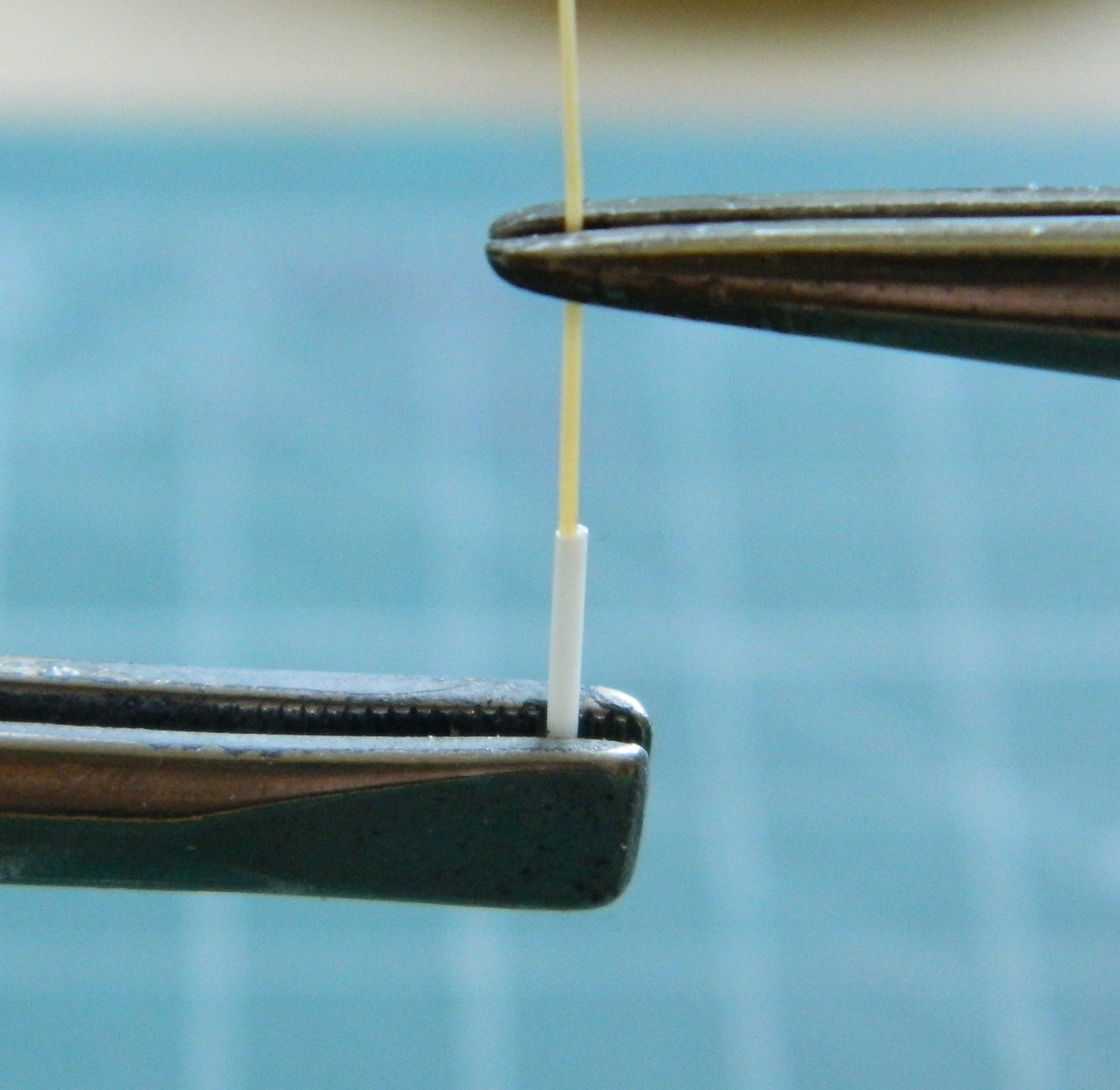

I marked the section of the ribs that needed to be trimmed back and dry-fitted frequently. It became evident that I had to remove enough of the ribs which would cause the lightening holes I drilled into the ribs to be sanded through the edge of. That means I either have to pop those ribs and stringers out and redo them (No. No way.) Or fix them in situ. I opted for that and I used a piece of 0.062″ (1.57mm) Evergreen styrene rod to fill the holes that had to be filled. The rod was a little bit larger in diameter than the holes I needed to plug, so I cut a short section, chucked that section into a variable-speed drill, then spun it slowly while tapering the end of the rod with a file:

Then I started filling the holes. Using styrene cement means that I have to let the glued part sit for a few hours (preferably overnight) so that the plastic, already very thin, would be as solid as styrene can be when I started working it. After a few days of glacially slow progress this way, I finally realized that I should be using the UV-setting resin for this, so I switched to that and the progress of filling holes went much faster:

Once I finished down the plugs, I went back at the ribs with the modified emery board until clearance was achieved:

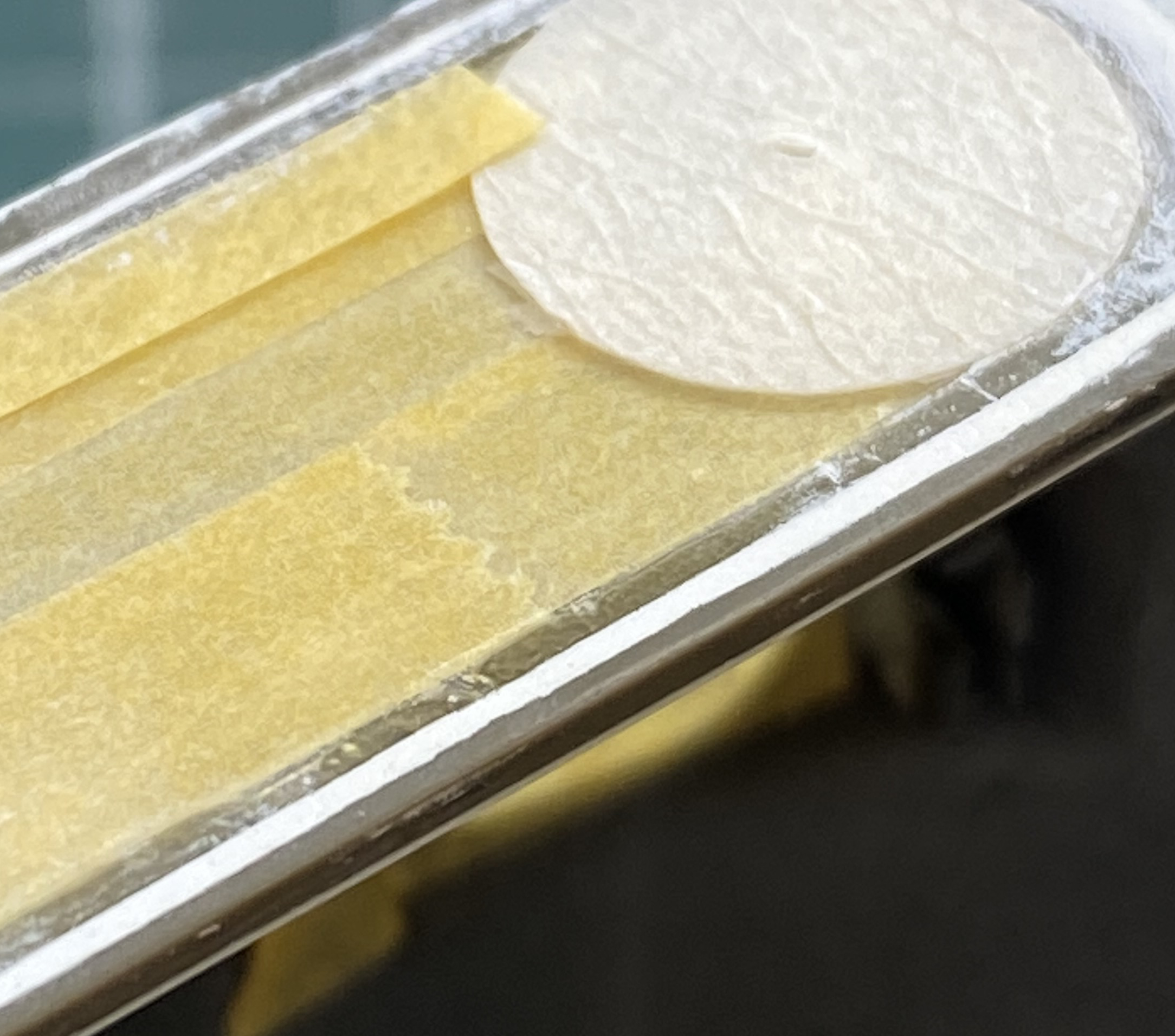

I have also been filling every available space in front of the pivot point (defined by where the main landing gear contacts the surface it’s sitting on) with weighty bits. Most of the added weight is lead. In addition to the flattened lead balls inside the nacelle, I stuffed what space was around them with lead wool on the right side and sliced .093″ (2.36mm) lead solder on the left side (you can see the lead in previous photos). Once glued, I lined the forward bottom with tungsten tape (this is used to adjust the weight/balance of a pickleball paddle, if you want any of it) and put another piece across the back of the lead balls. This shows how much added weight there is:

The next step is to paint the inside of both nacelles flat black. Since I’m going to be loading the airbrush, I also want to paint the engines while the airbrush is loaded with the flat black.

But that’s it for this month…

F7F-3 (AMT/Italeri) 1/48 Scale Build #2 –Continuing to Populate the Engine Nacelles

I debated whether or not to do an update this month because I haven’t spent much time at the workbench. (You can probably figure out what I decided.) Continuing my departure from normal aircraft models, I’m still working on the landing gears and nacelles instead of starting with the cockpit.

I was curious as to how much the nacelles and engines weighed after stuffing things with lead and tungsten (answer, each set was about 19.6g, and we’ll see if that helps…it certainly won’t make things lighter, which is the point):

I successfully squared the front and rear of the landing gear openings that I’d started last month:

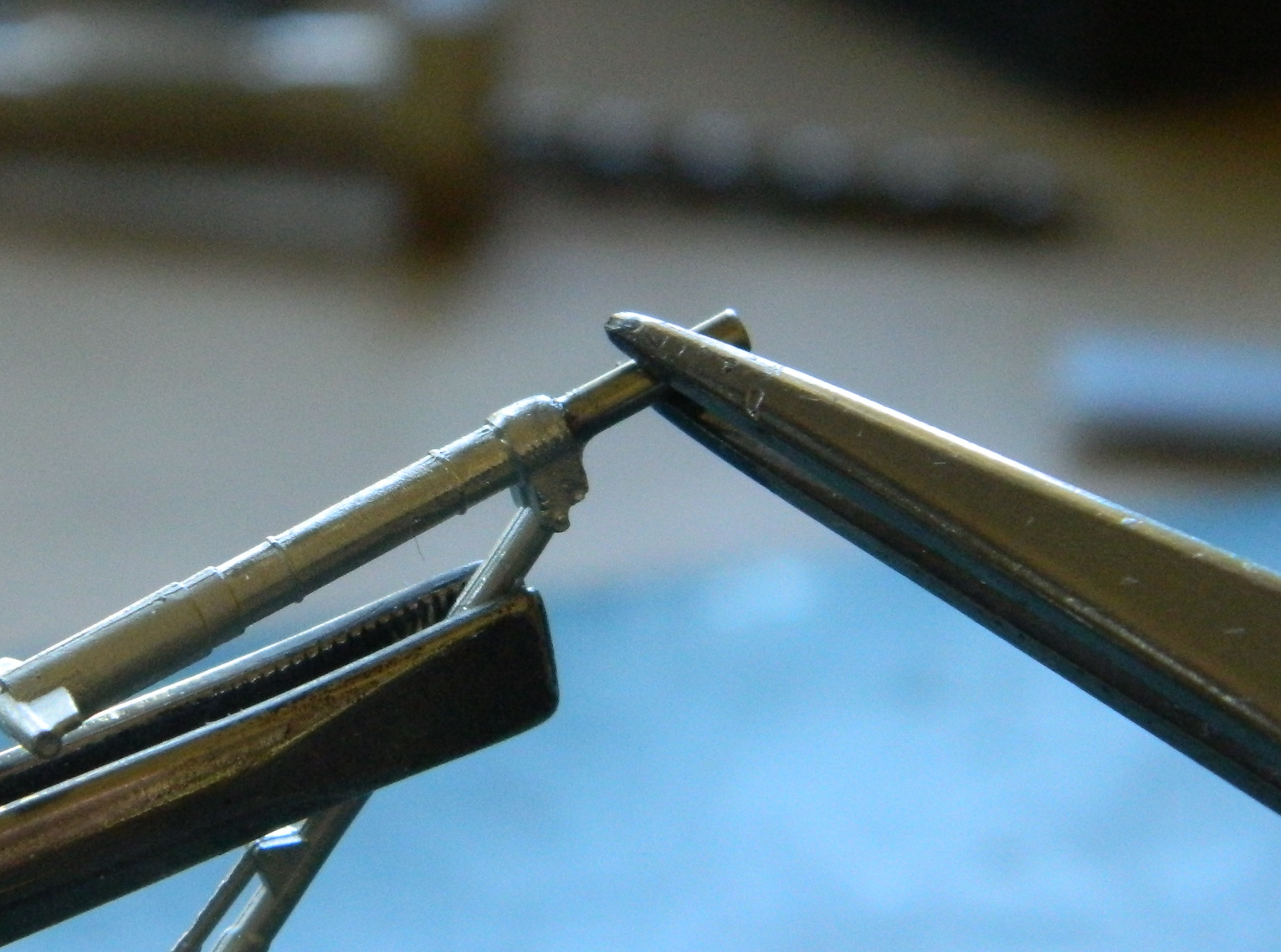

The SAC landing gear parts needed cleaning up. During that process, I discovered that some cleanup had been “done,” which I put in quotes because what was done was less than acceptable. A rod is supposed to have an outer surface of the oleos that is parallel all the way around and none of the SAC parts had been done that way. They were lumpy, so they had to go. I started by cutting the nose gear strut apart (and if you look closely at the stub of the oleo on the left, it’s evident how out-of-round the outside of it was):

Then I drilled the socket that the paperclip stub would be glued into (apologies for the lack of focus but that’s the best the fornicating camera would do):

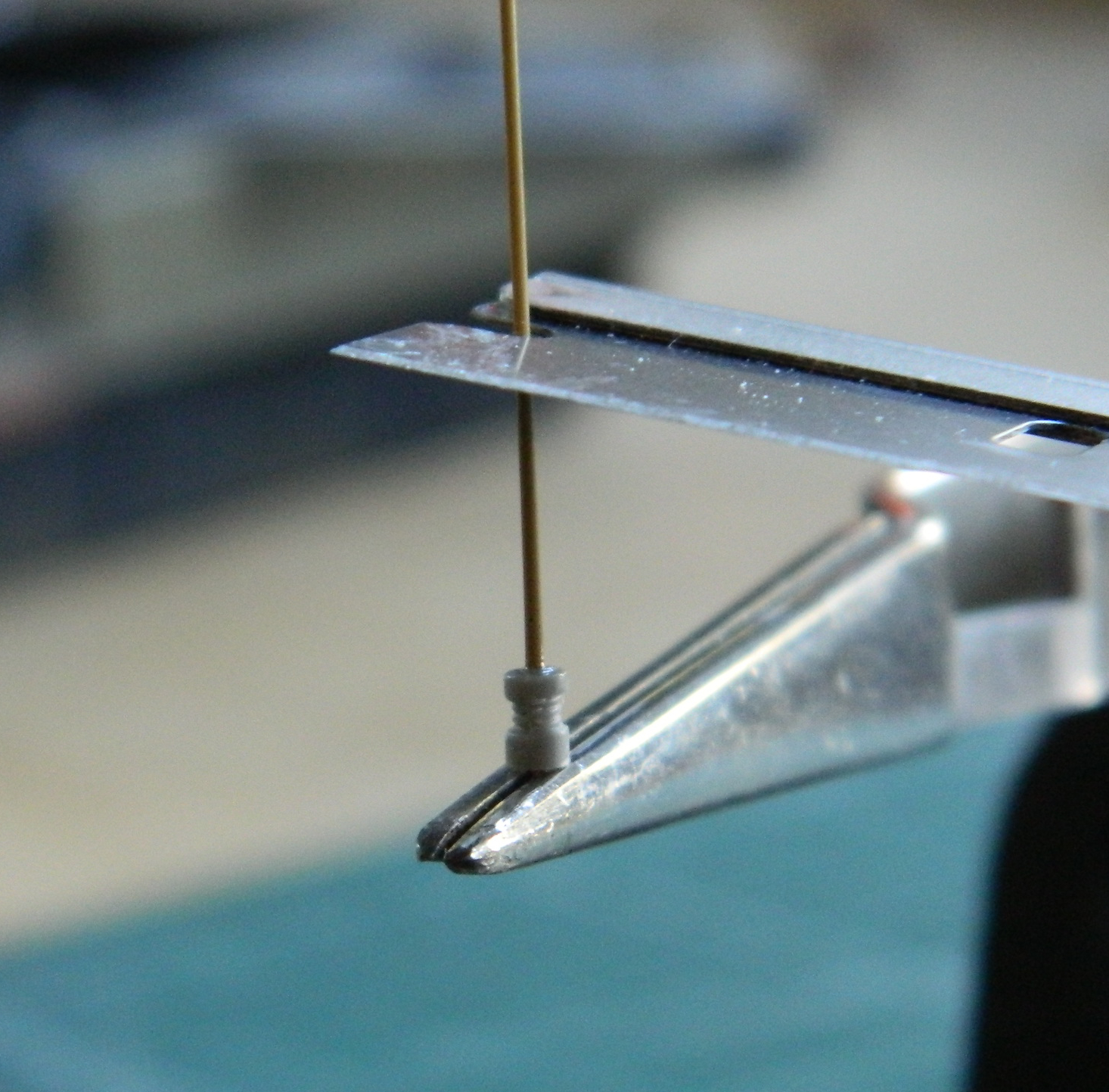

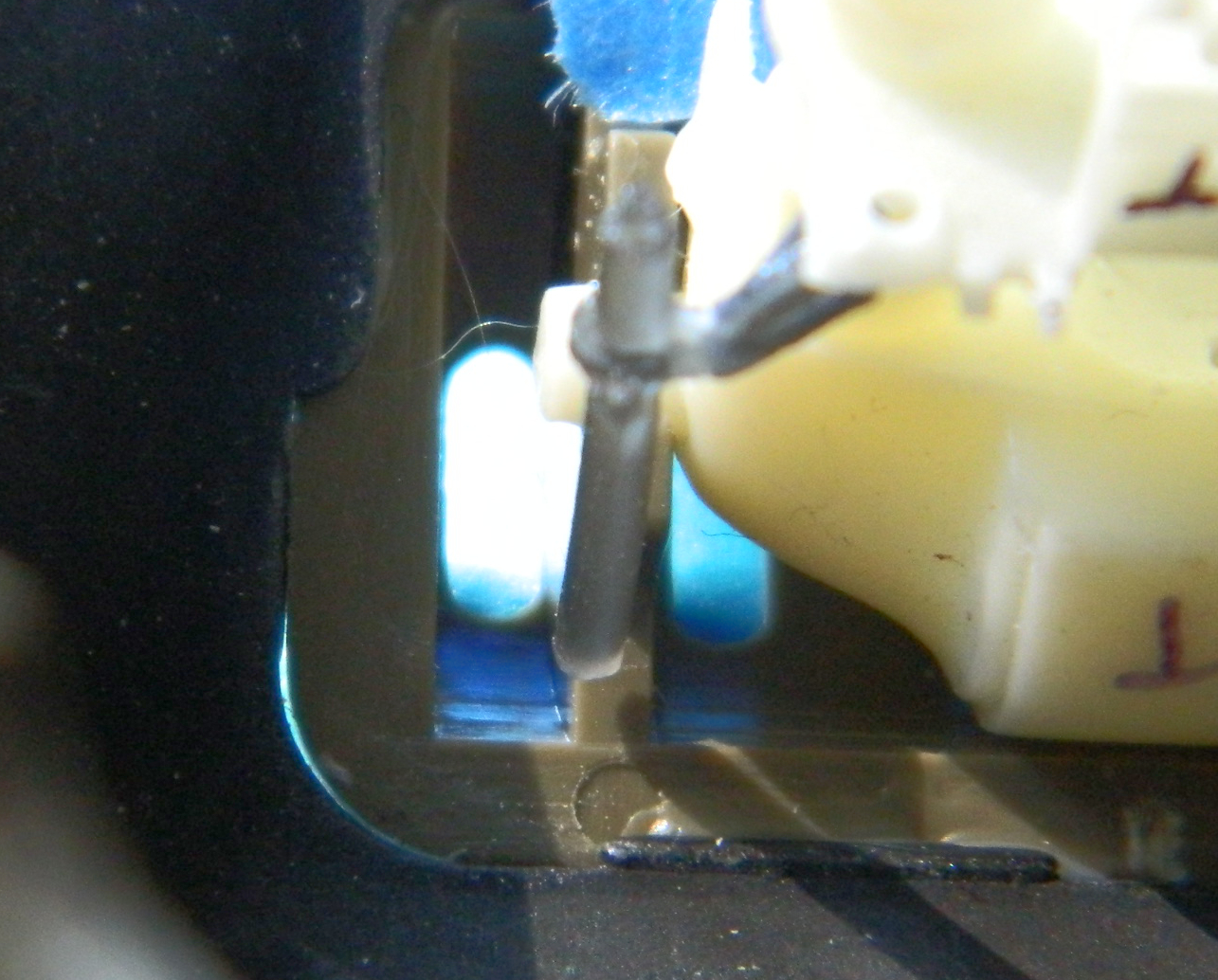

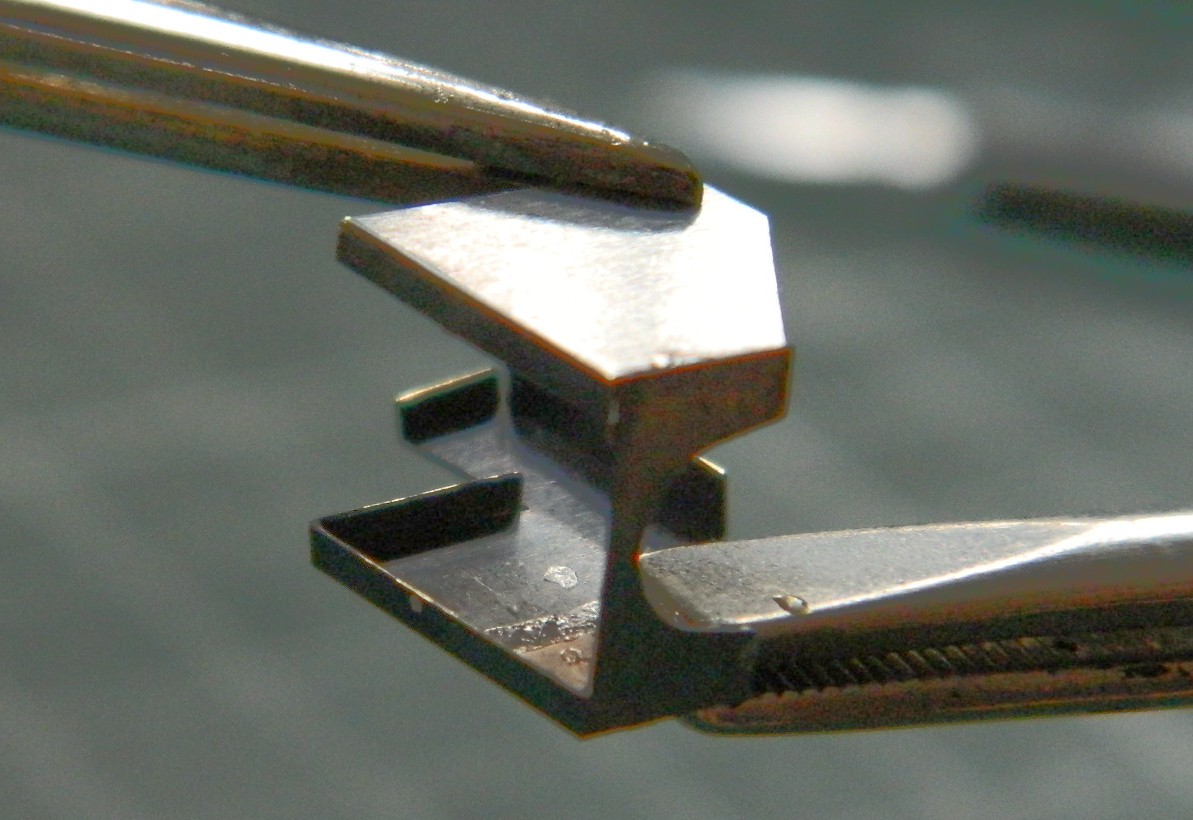

I cut the remaining stub off the nose gear leg, drilled another socket, and then cut and filed the welding rod. Once fitted, the jeweler’s tweezers held it in alignment and superglue should keep it there:

And once that had cured, the bottom of the landing gear was glued on:

That was easy, the main landing gears were not and fought me, requiring a couple of removals when I realized that the lower part wasn’t quite aligned (and somehow I managed to cut one too short so that had to be redone) with the paperclip stubs:

I’m not going into the massive annoyance(s) of keeping the soft, lead-like alloy, straight and properly aligned with the places they have to fit inside the nacelles. It happened and I got it all straight…I think.

That was the easy part of the past month. The rest of the tedious and annoying month (more because that my mind isn’t really very interested in tedium at present) was populating the inside of the nacelles with the internal support structure. The easy part of that was fitting the PE parts (there’s another set at the front of the opening which you will see in other photos because I forgot to take a dedicated photo of them):

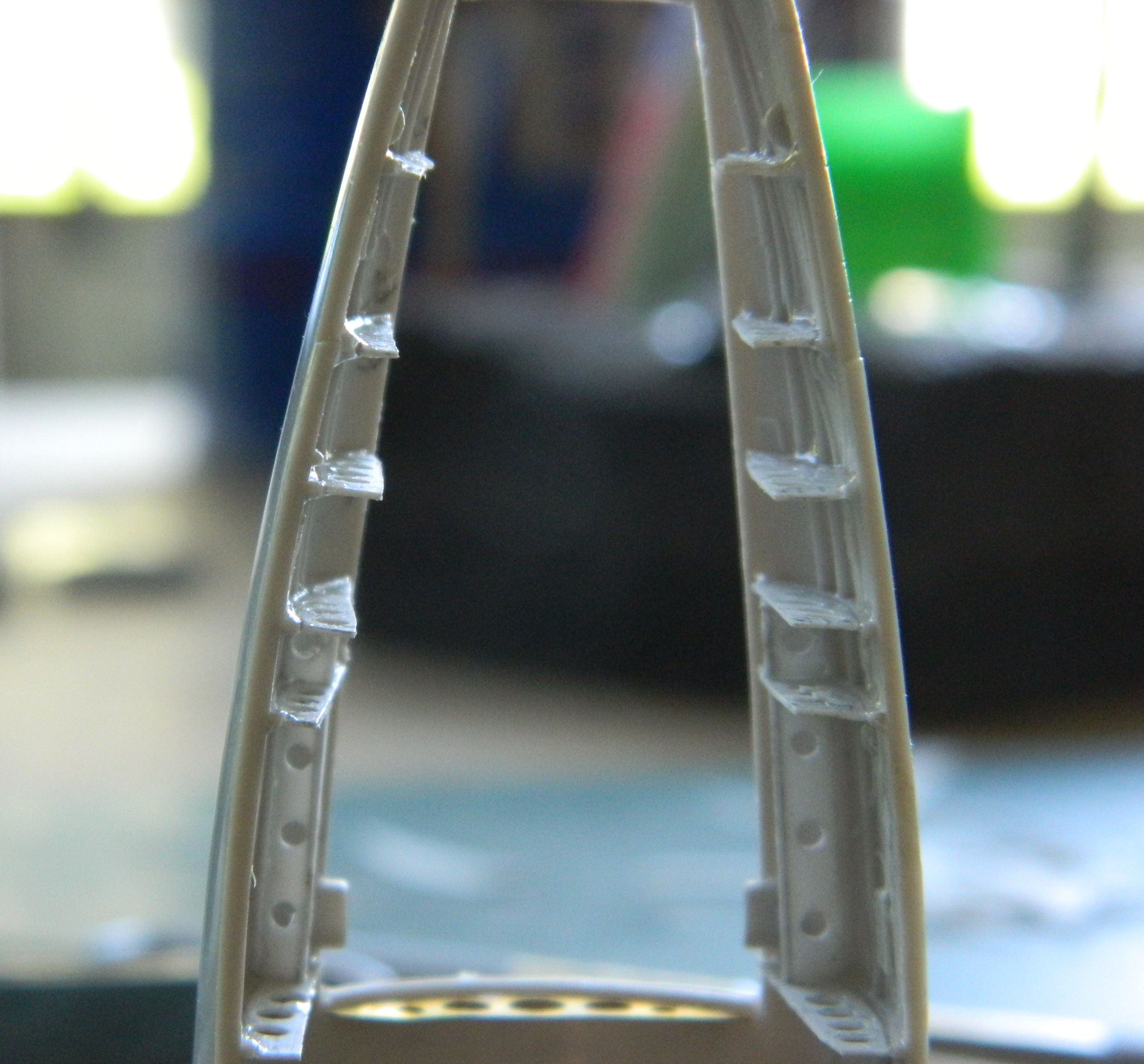

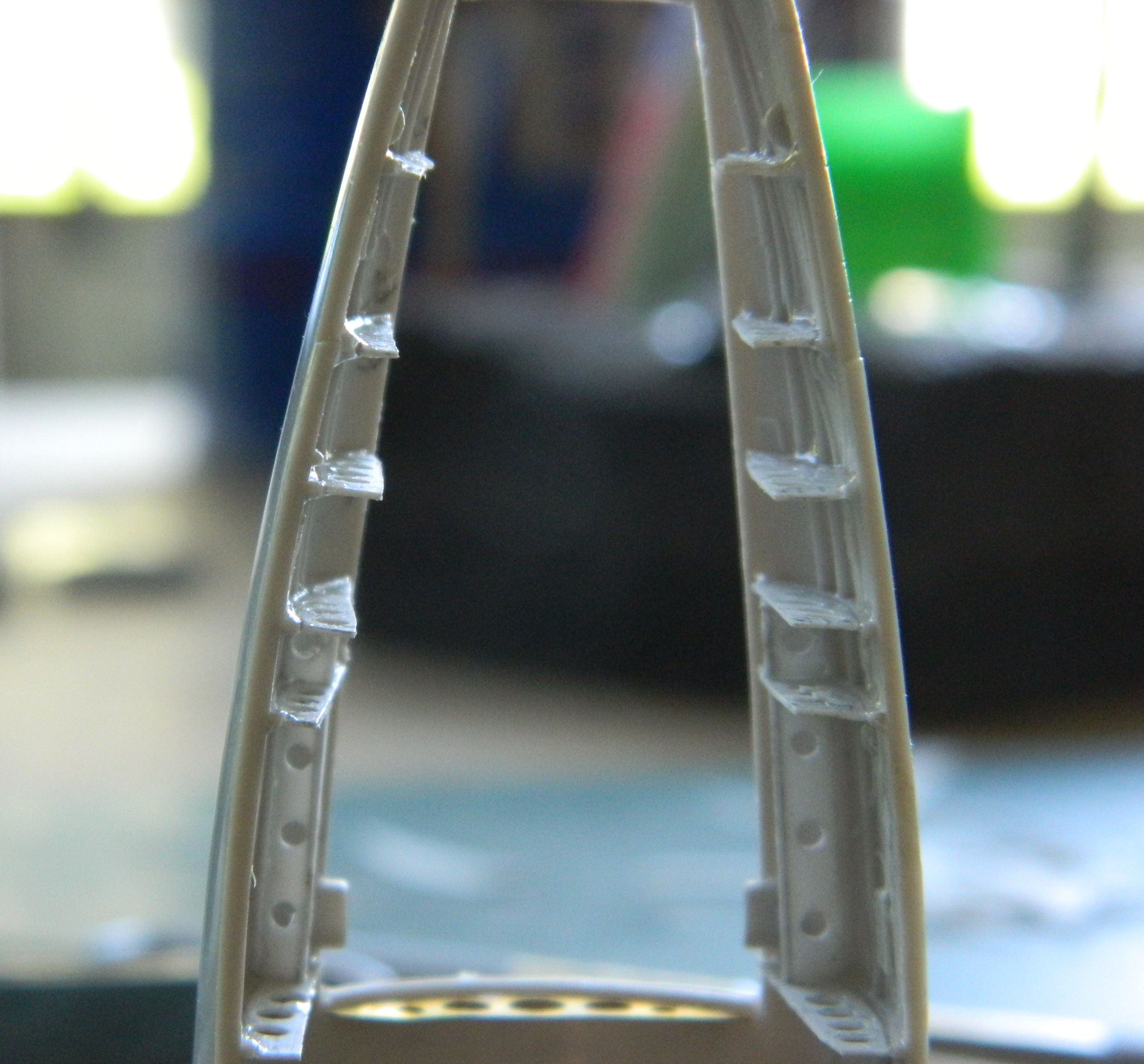

Each of the curved ribs is supposed to be much deeper, but this is where the parts I have to make will be glued. There are 12 for each side for a total of 24 delightful ribs I have to make because I just love matching inside curves (NOT):

If I needed any physical manifestation of how my mind is off center, this job certainly did that. First I had to cut the stiffeners and match the curves, for which I used 0.010″ (.254mm) styrene scraps:

Then dry-fitting showed me that I’d cut some of them a bit too narrowly, so I had to reattach scrap bits to rectify that (those?) mistake(s?):

Lightening holes were punched into the stiffeners of the actual aircraft. To replicate that I started with the punch/die set but wasn’t very pleased with the result and switched to drilling the holes:

I attached one and then stopped:

I stopped because when working with something so thin, there isn’t a lot of gluing surface to hold things together well enough to withstand the (albeit gentle) handling while constructing. I decided to (finally) give UV setting “glue” a go. Glue is in quotes because this stuff, though sold as an adhesive, isn’t an adhesive at all. It’s a UV setting resin, much like the material that dentists are now using to fill cavities instead of the old amalgam. It acts like an adhesive because it will hold things to each other once cured. To see which I liked better, I did the first nacelle with the UV resin and the other nacelle with my traditional Tamiya Extra Thin. Each has their benefits and liabilities and I ended up using the procedure of tacking one end of the stiffener with styrene cement, gave it a few minutes to goo up, and then used that as a pivot to align the remainder of the stiffener which I then fixed in place with the UV resin:

Between the two methods of affixing something, I achieved what I wanted:

I dry-fit the nacelle to the wing and by doing so realized that I’d trimmed off too much of what I’d added back and had to redo that:

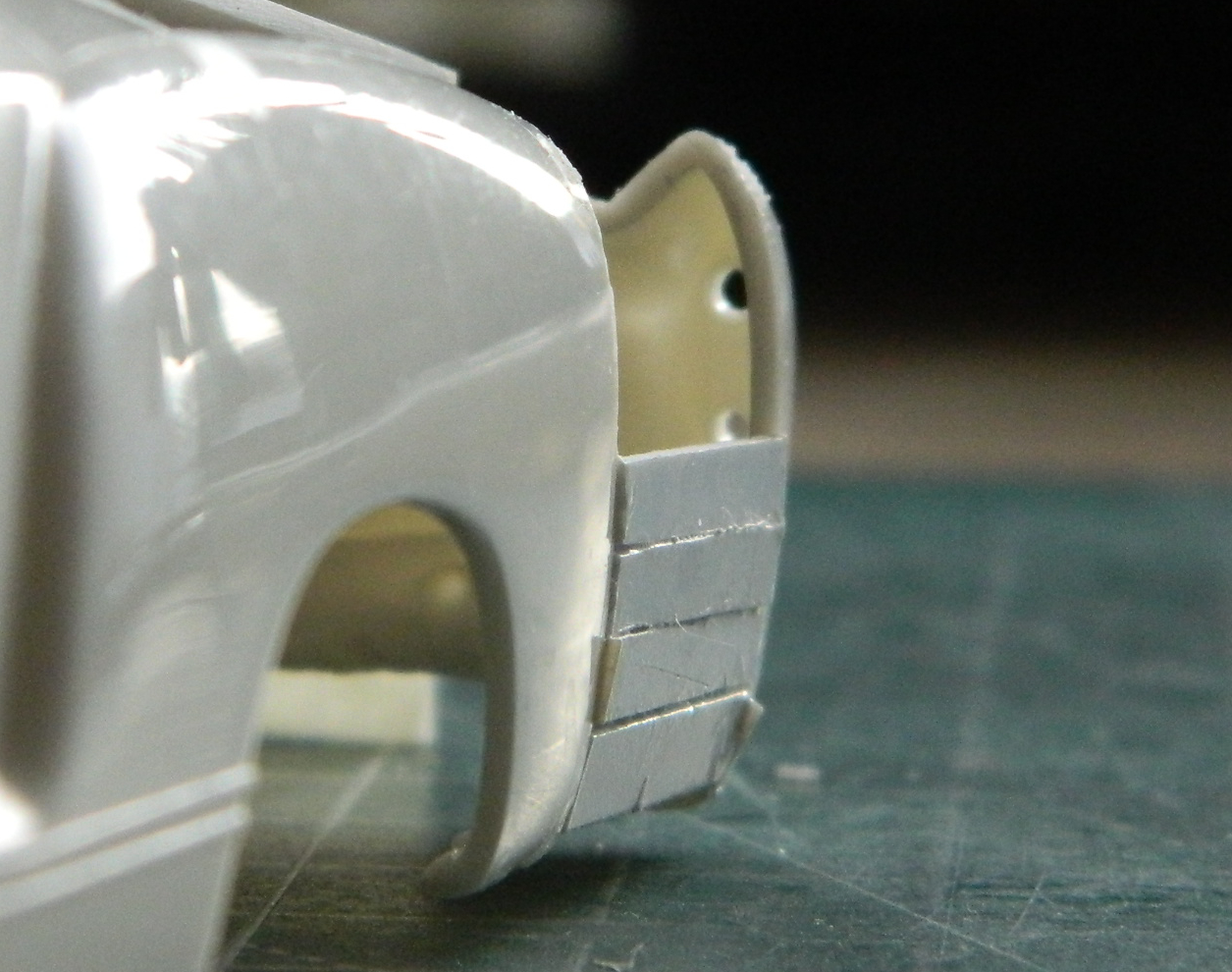

Having fixed that (I hope), it was time to start adding the rest of the structure. This bit replicated (I hope) the five horizontal stiffeners on each side of each nacelle. I got one done:

At this point knowing that I have 19 more to do made the (already borderline hot) circuit breaker in my mind pop. This is as much as I have to show for this month. We’ll see if I have more inner endurance next month for tedium.

F7F-3 (AMT/Italeri) 1/48 Scale Build #1 – The Parts and a LOT of Things to Add Weight

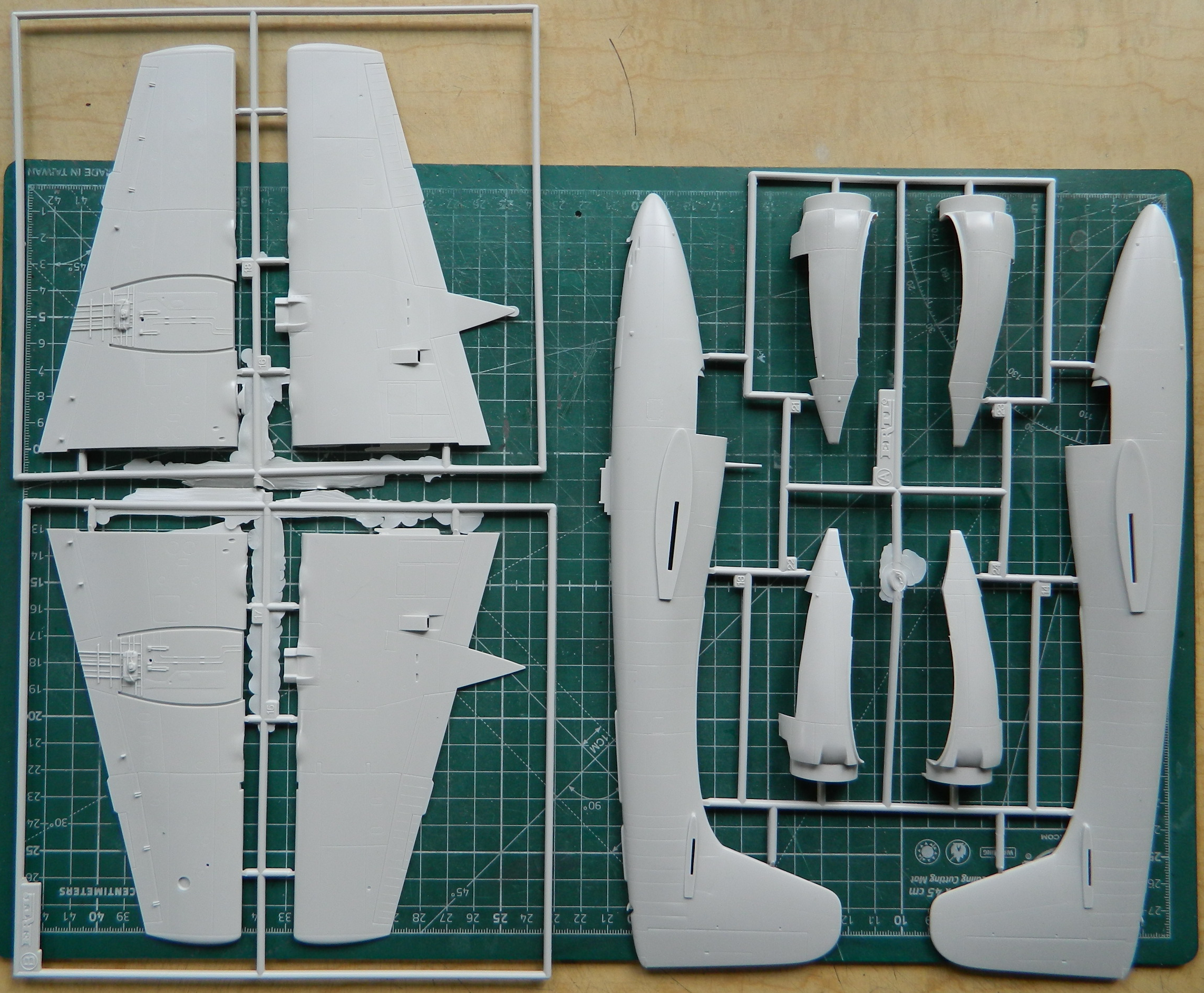

Next on the bench is this:

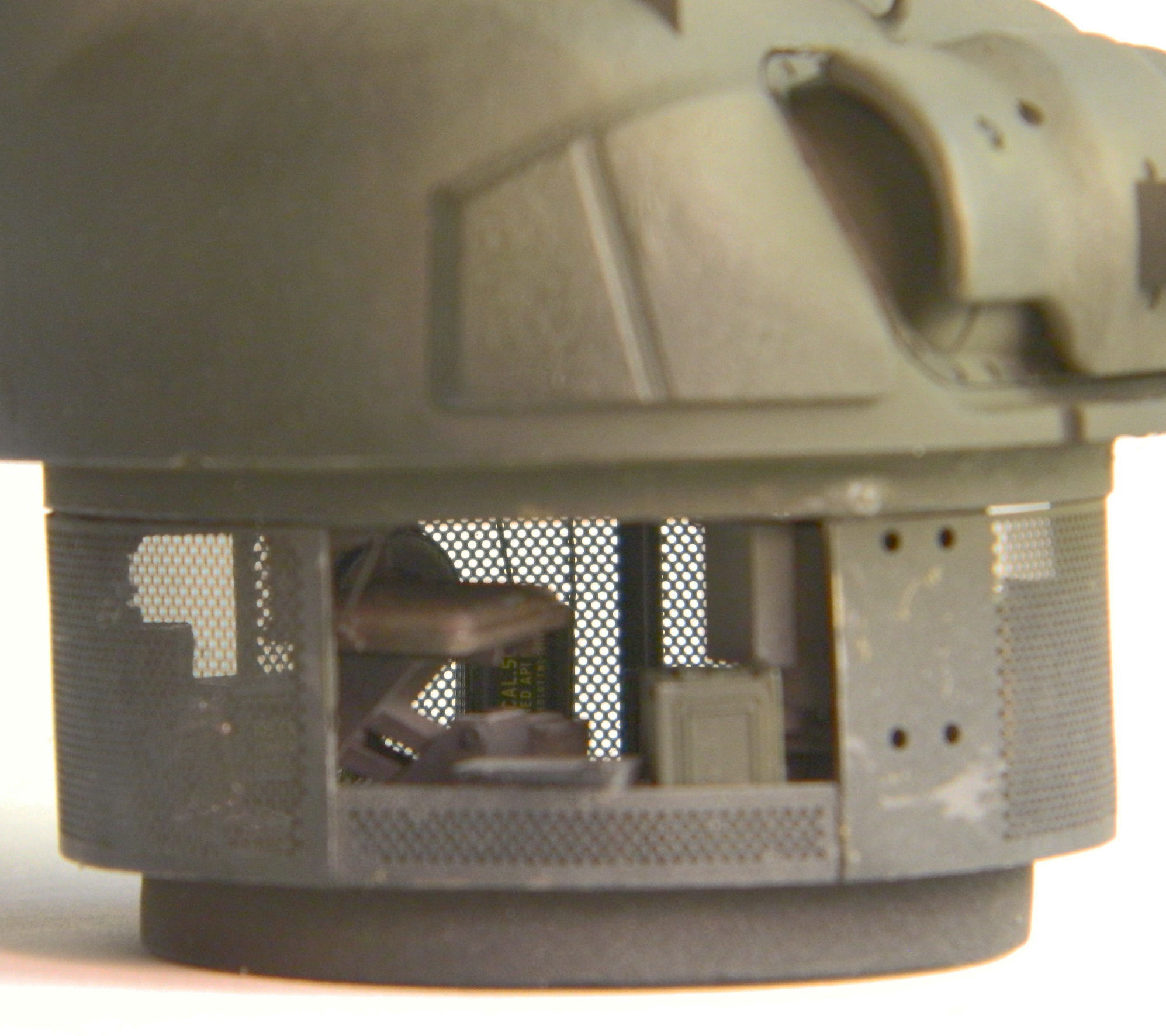

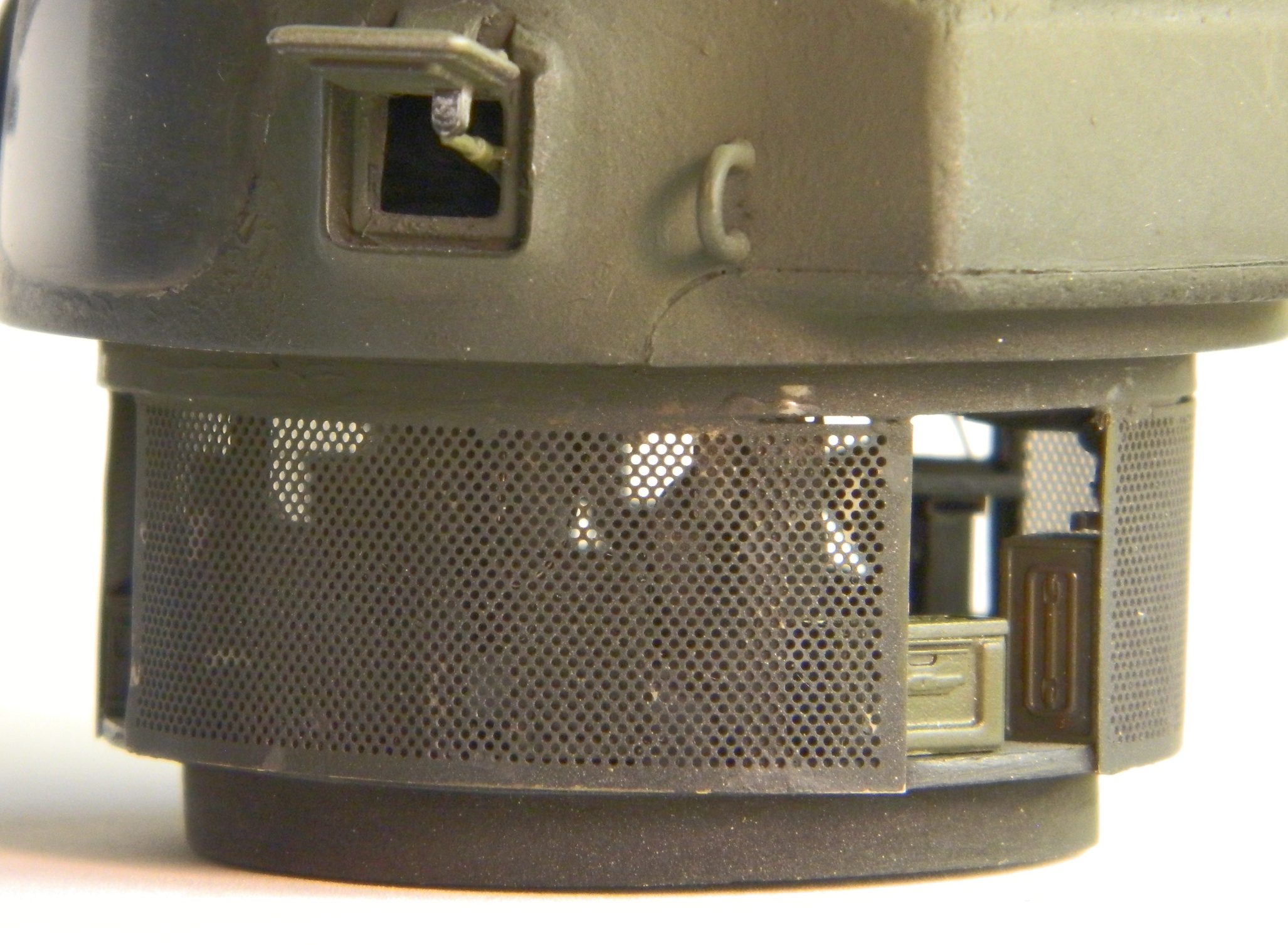

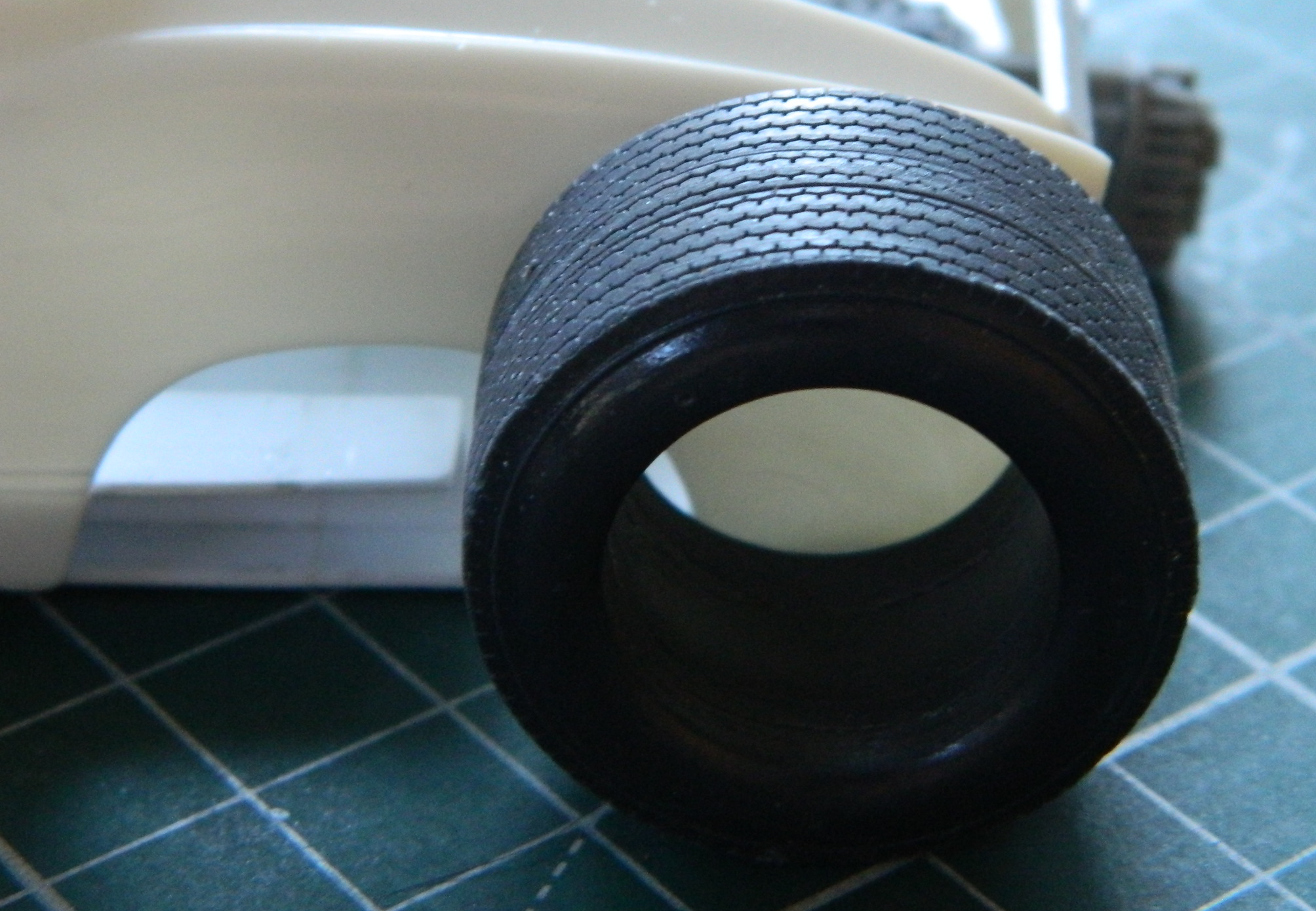

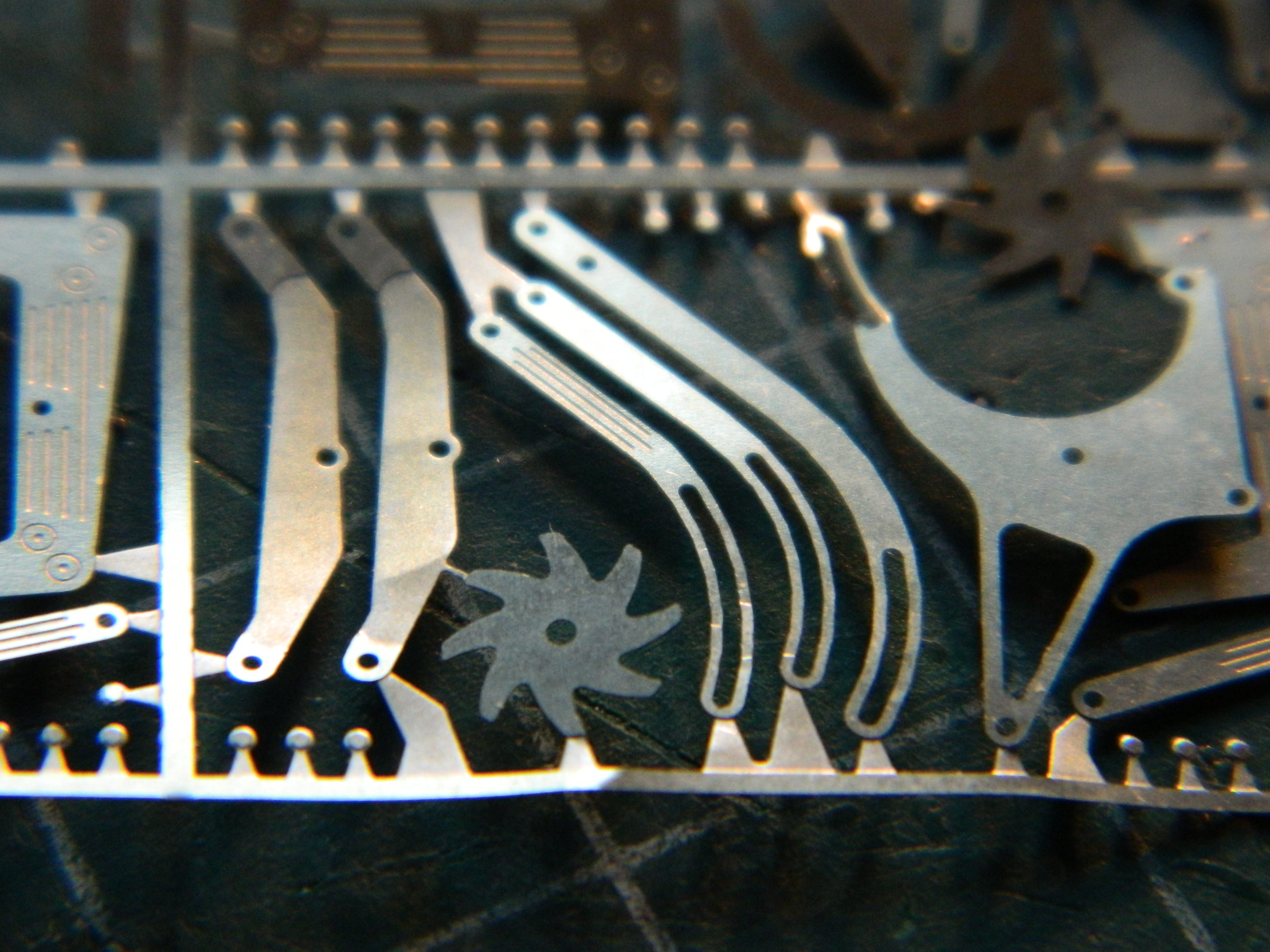

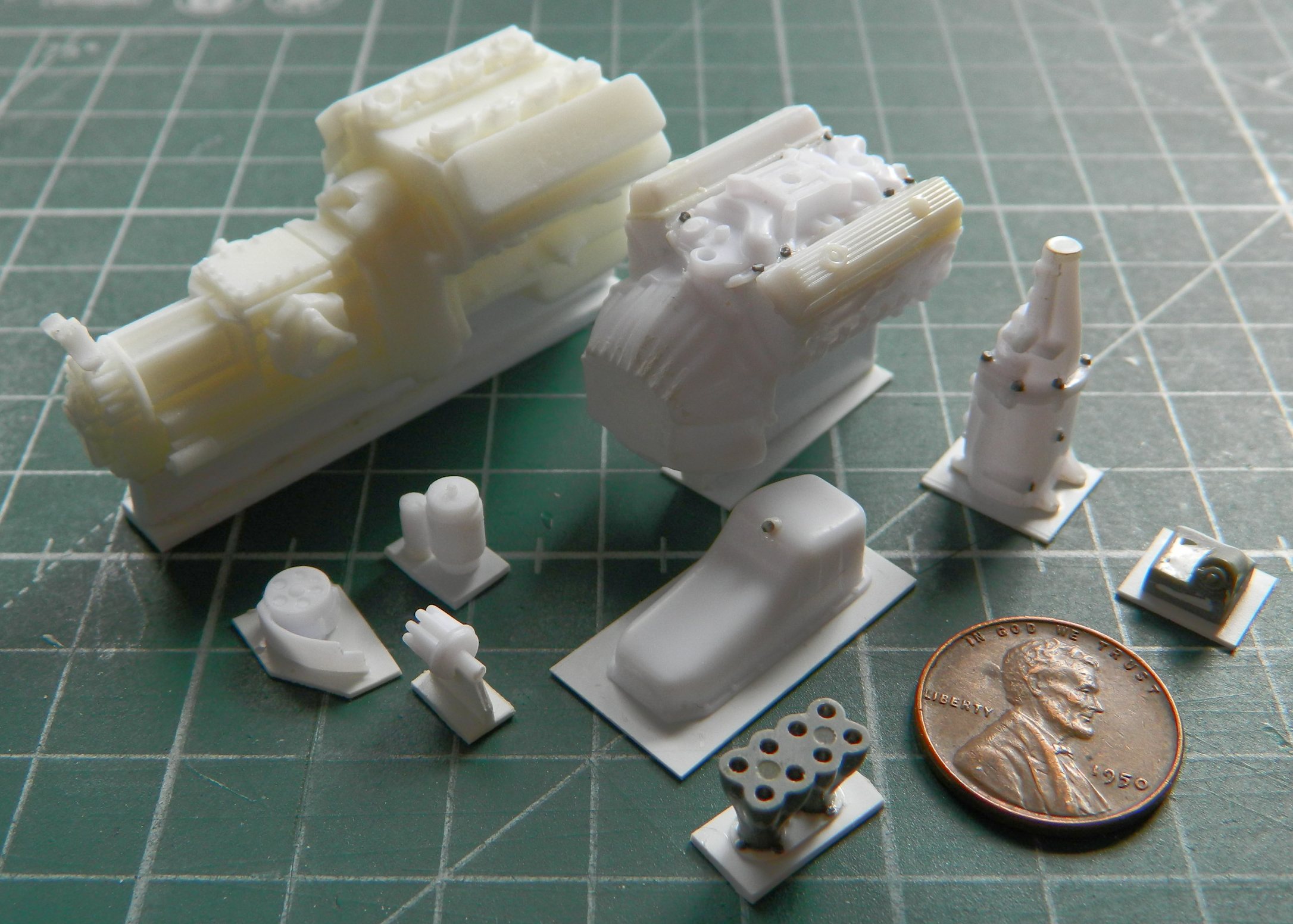

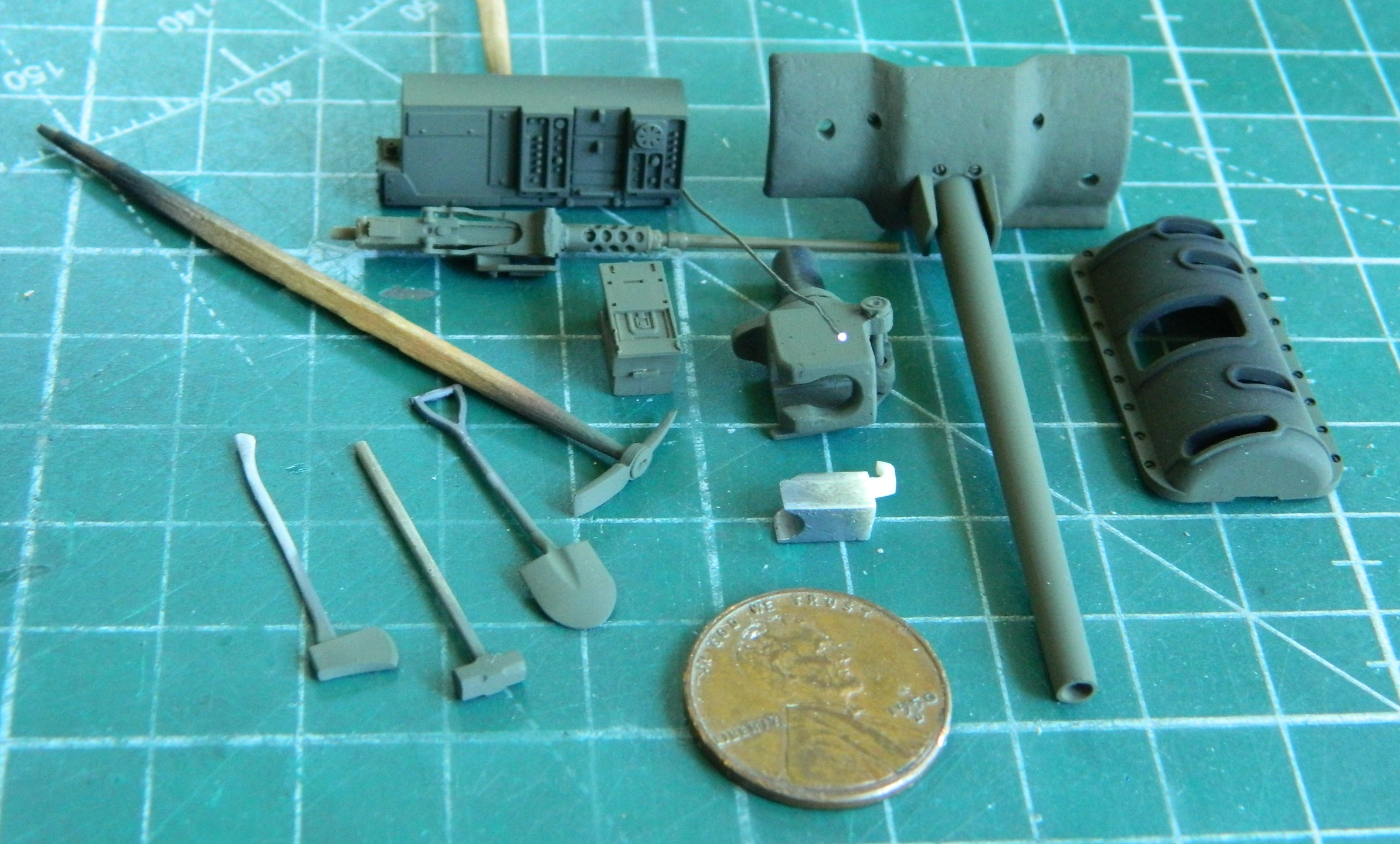

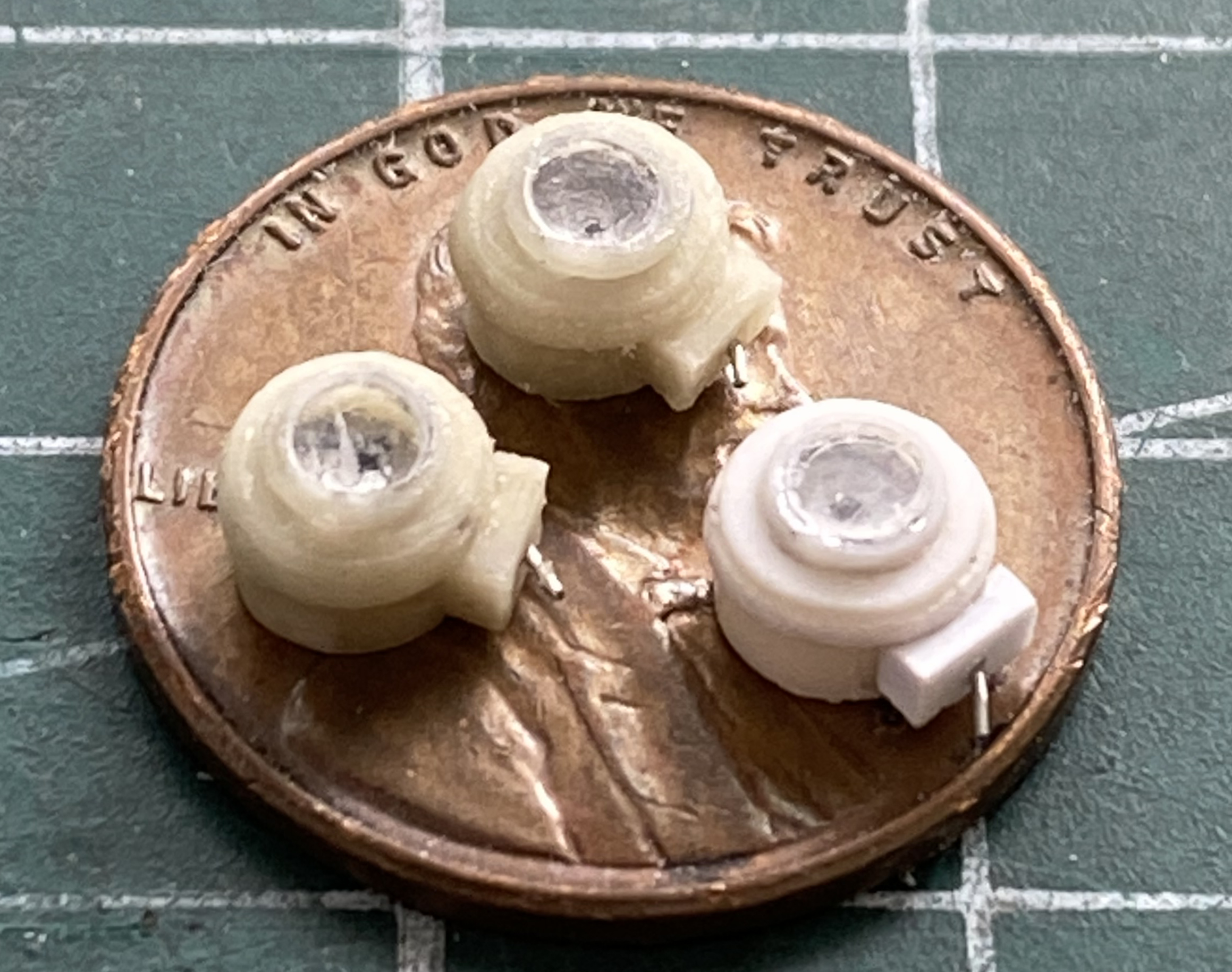

Not a lot of parts (for a change), though I’ve no doubt that I can increase the parts count (not at all a change). There isn’t a lot of AM bits available for this kit. I did get lucky, however. The kit comes with “rubber” tires (::retching noises in background::) and I’ll be able to replace them with CAT 4 resin. Eduard also makes a PE set for this kit which I’ve acquired. Quickboost also makes a pair of P&W R2800 engines specifically for this kit and also acquired (the vial of little shiny beads is to supply control knobs that PE “represents” as flat parts):

I’ve read several build reviews of the F7F (in a couple of other variants) and each builder says essentially the same thing: “I wish I’d put more weight in it!” My initial eyeballing of the kit shows why…there aren’t that many place to put weight. I went into my bits inventory and pulled out all the lead anything I have:

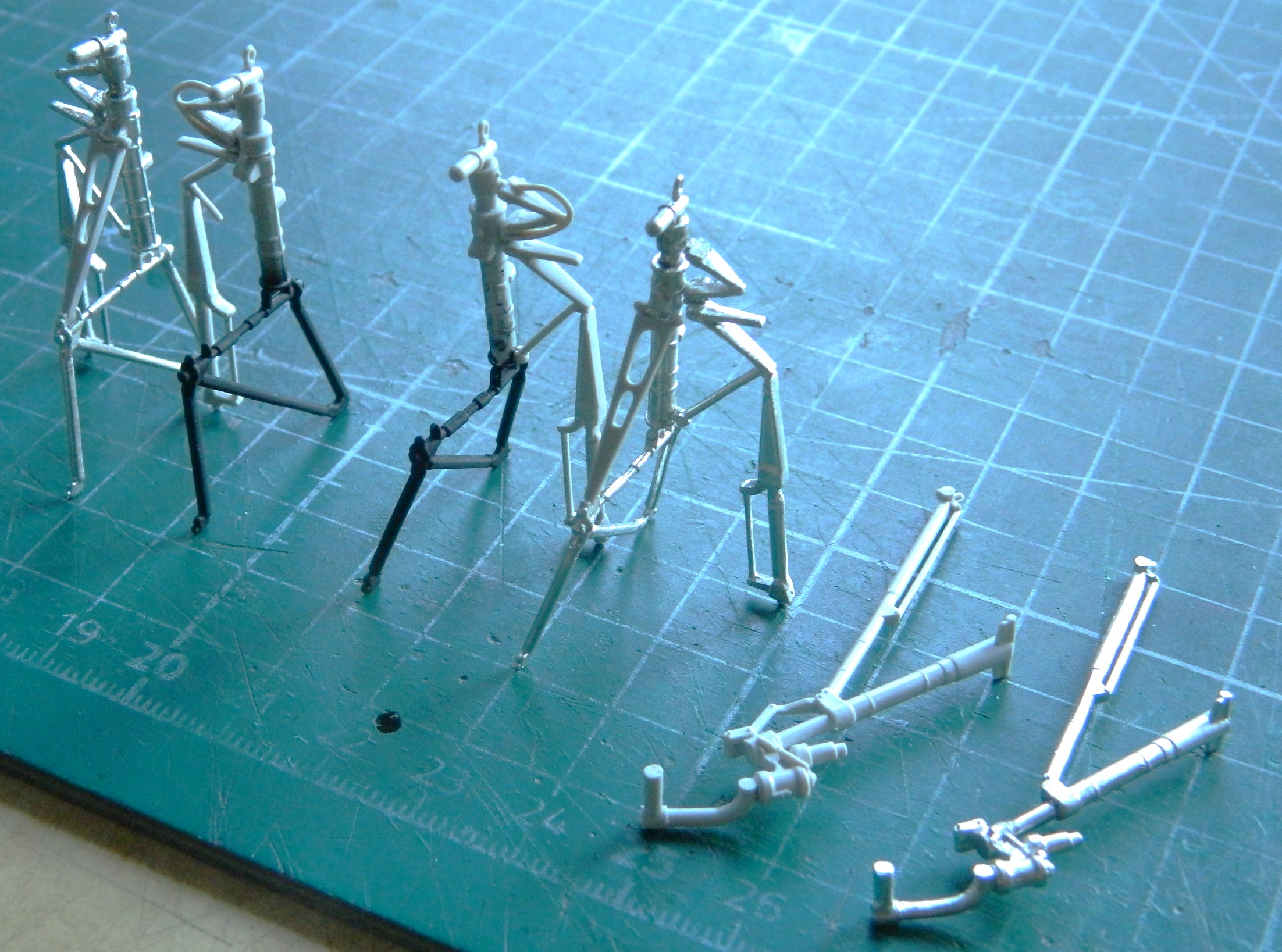

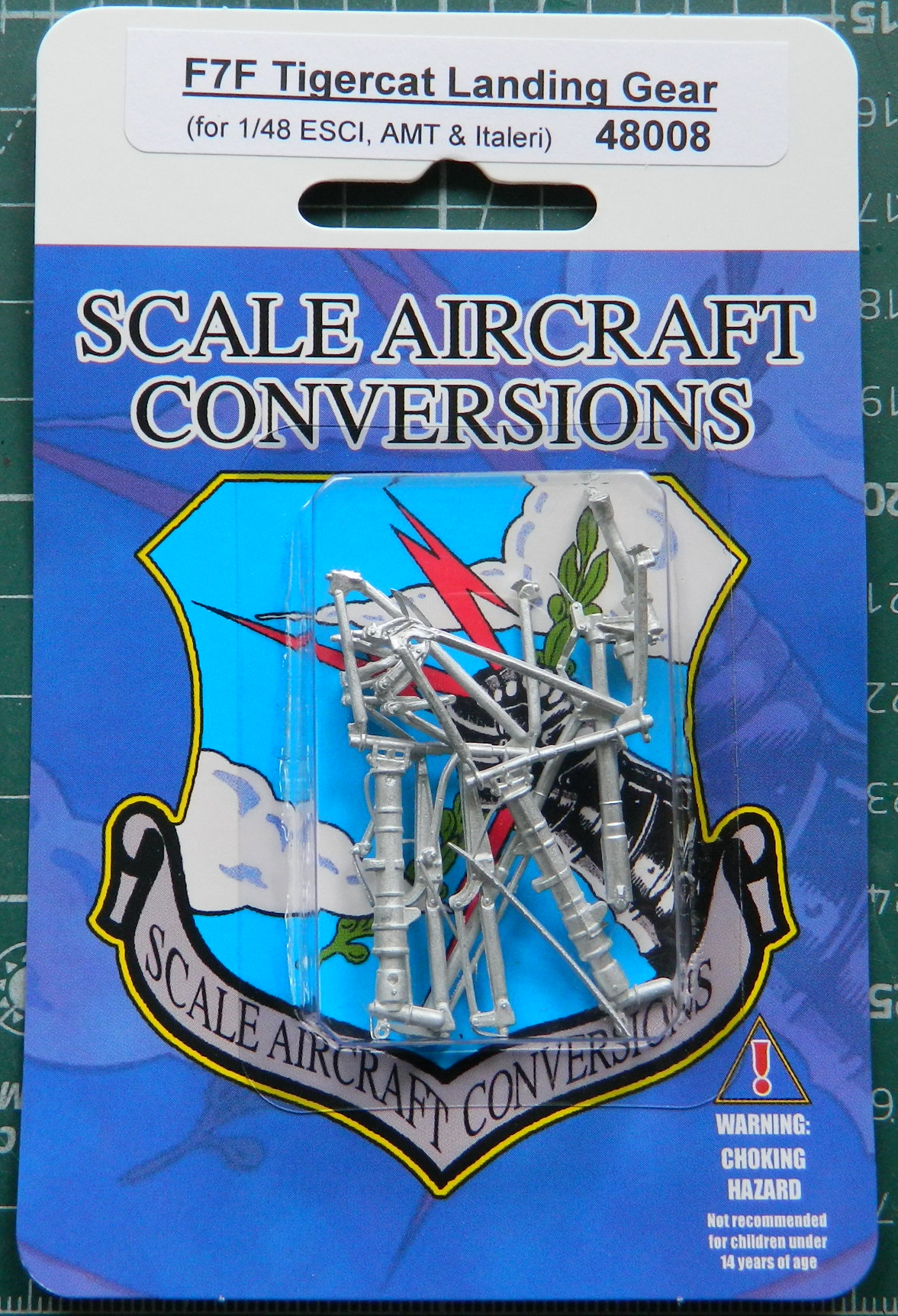

See that tungsten tape? It’s over $20! I was going to get lead tape instead because it was about a quarter of the cost and then I thought. Once I recovered from the novelty of that, I decided to go with the tungsten tape because tungsten is heavier, and that decision was encouraged by the thought that I spend substantially more than $20 for a tank of gas that I intend to burn. Since I’m going to be adding a lot of weight, I decided to try metal landing gear as a replacement for the plastic equivalent:

SAC produces these parts by taking a copy of the kits’ parts and then casting them in metal. The problem with that is that they don’t clean up the originals to my level of clean up. But since I’m going to have to clean something, I prefer to clean up landing gear that will support the added weight I intend to add. I don’t want this thing to look like a giraffe getting a drink in a few years. How likely would that be to happen if I used the styrene landing gear? Don’t know and don’t want to find out.

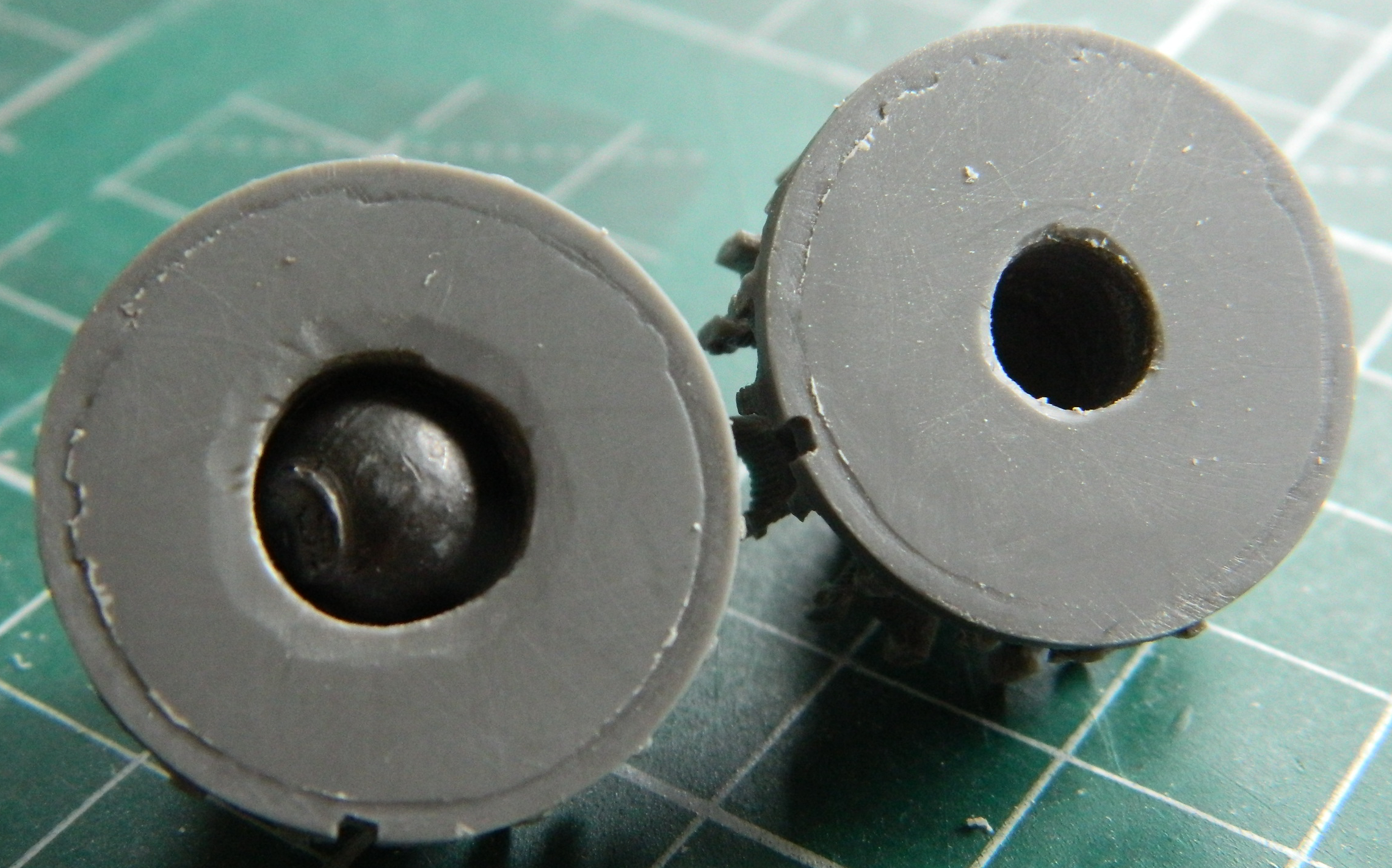

Typically when I’m doing something with wings, I start with the task(s) that enable me to close up the fuselage, so that usually means I start with the cockpit. Not this time. Not having this be a tail-sitter is weighing on (what’s left of) my mind (yes…puns are still intentional). Since I’m planning to stuff Weighty Bits anyplace I can fit them, I decided to start with the engines and I even have a reason. ANY place in front of where the main landing gear touches the surface will be stuffed with whatever Weighty Bit will fit. I intended on drilling out the backs of them to accept lead balls. The .44 caliber are too large but the .36 calibers are (almost) just right… that all starts by assembling the engines:

I found out that the .36 caliber balls are just a wee bit too large when the drill bit started biting away the engine cases. I certainly stopped that as soon as I saw what I was doing! I’d hoped to fit two balls (don’t go there) (which of course you have) into each engine but there isn’t quite enough room for both:

I can’t get the ball out so I spoodged it thoroughly with superglue and the other one I stuffed with lead wool. The glued ball holds the engine together well enough to obviate my Olympic-grade whining.

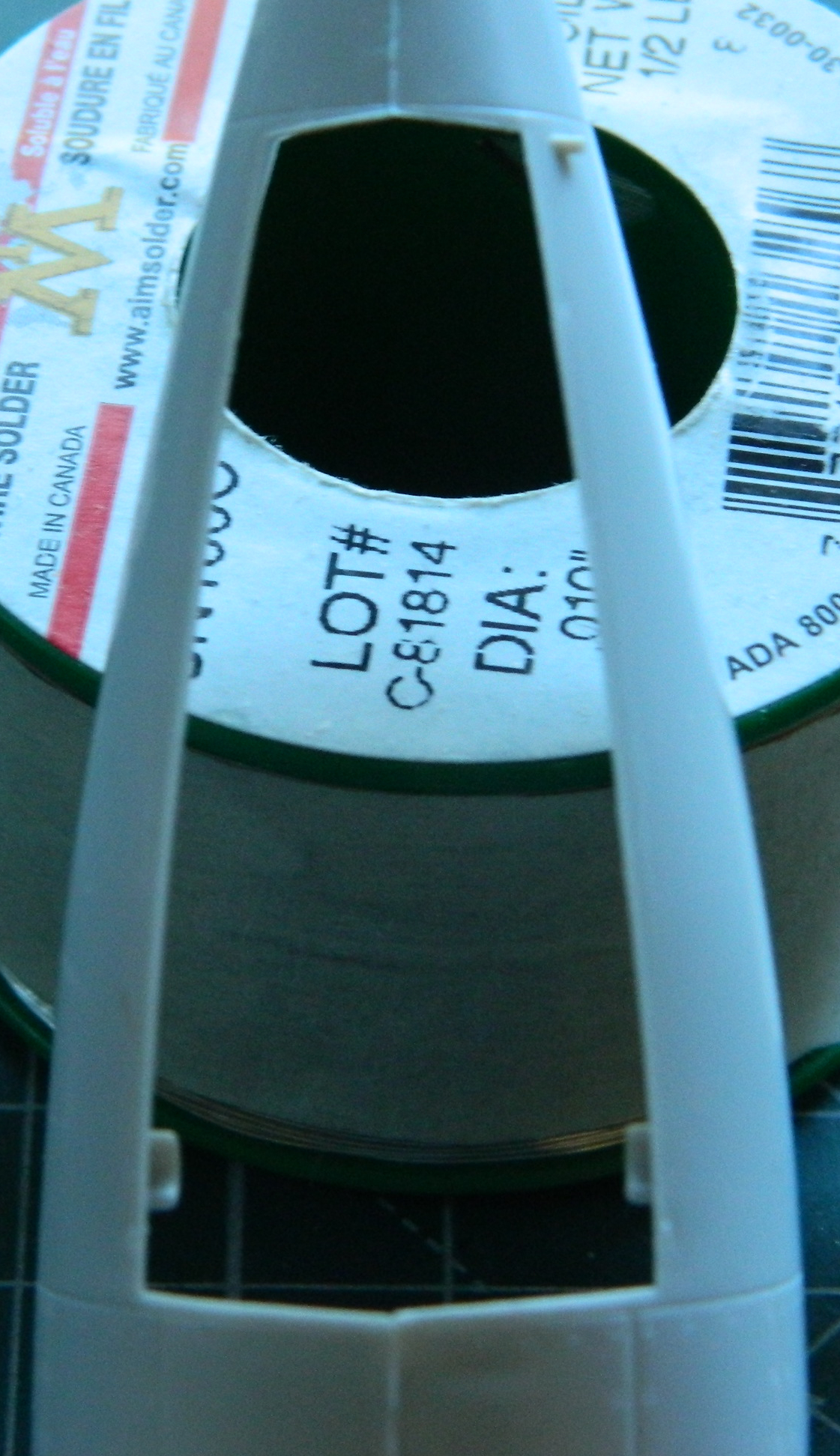

While I was in a lead-stuffing state of mind, I noticed that the cowlings have a little space at the inner front that I can stuff with solder:

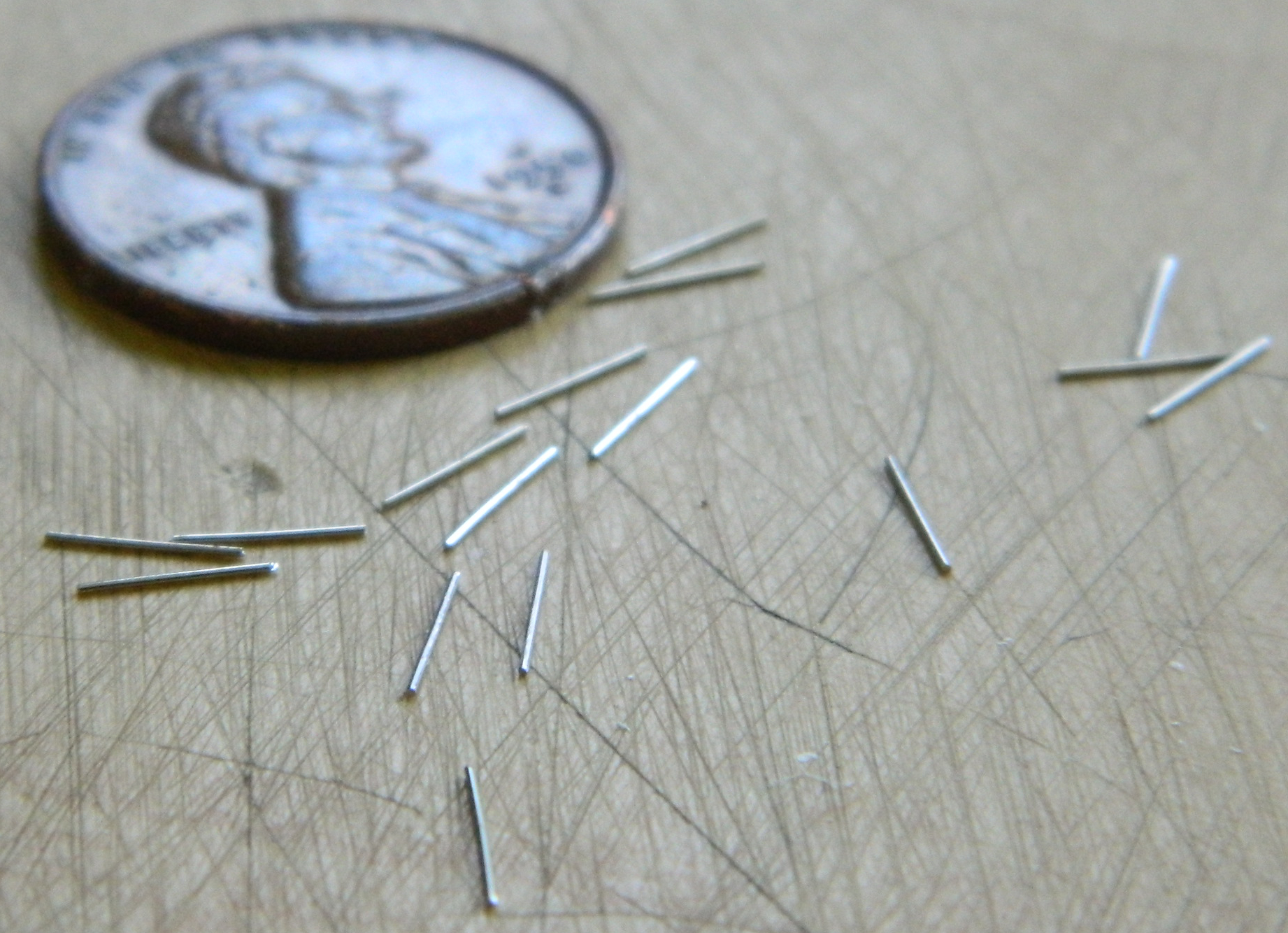

While letting the BitB work on this aircraft’s weight balance problem, I decided that since each of the 18 cylinders of each of the two engines need pushrod covers, I figured out the length I needed and started snipping wires for them:

And once I had the 36 wires cut, might as well glue them into place before I lose most of them:

Once I’d added all the pushrods to the first engine, I added the last bits to the front engine cover because I wanted to see just how much room I have inside the cowlings with the engine where it will be, approximately:

Enough room for the tungsten tape!

And once I had one done, there was the other:

Looks much better than the supplied engines for a LOT less effort:

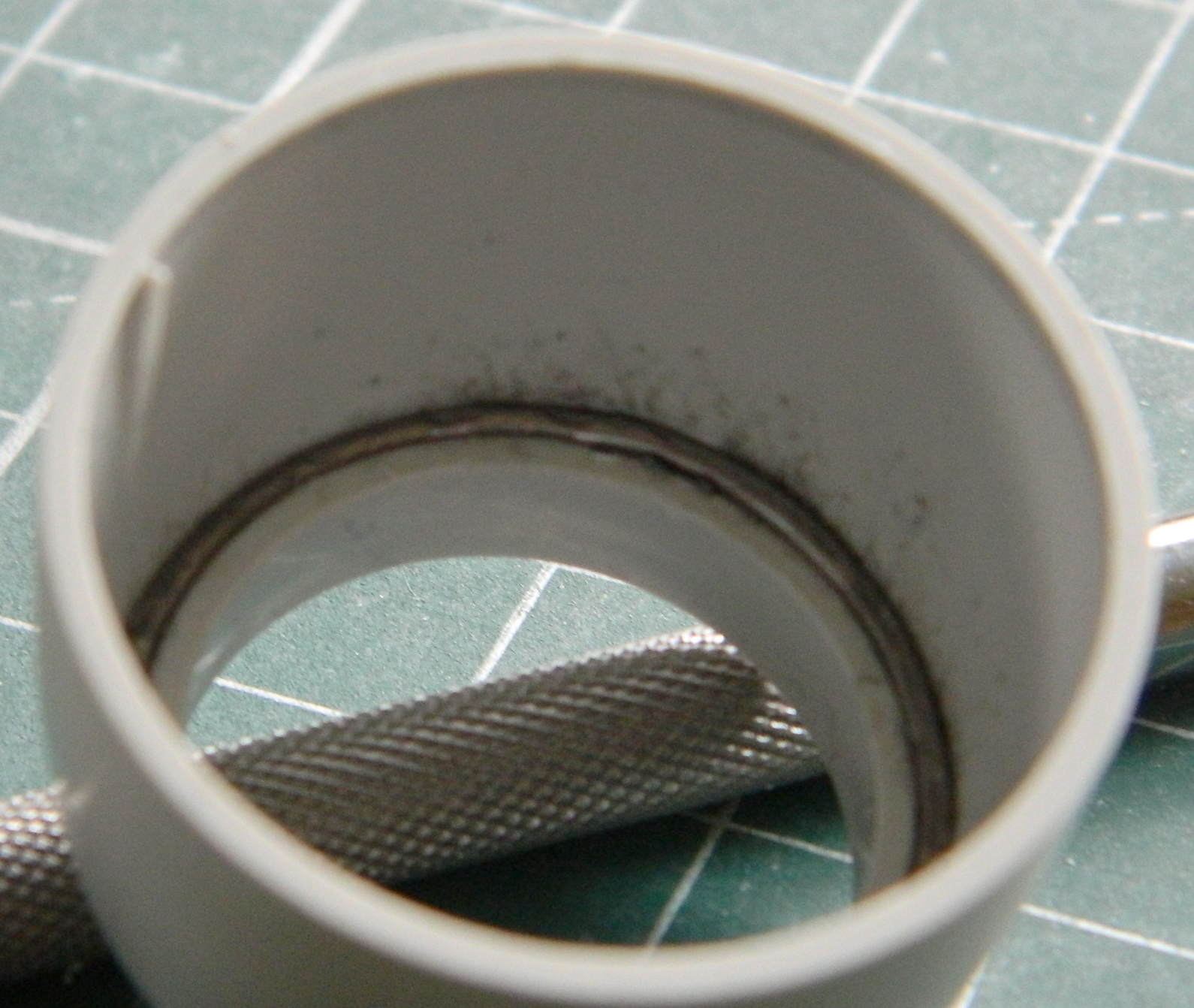

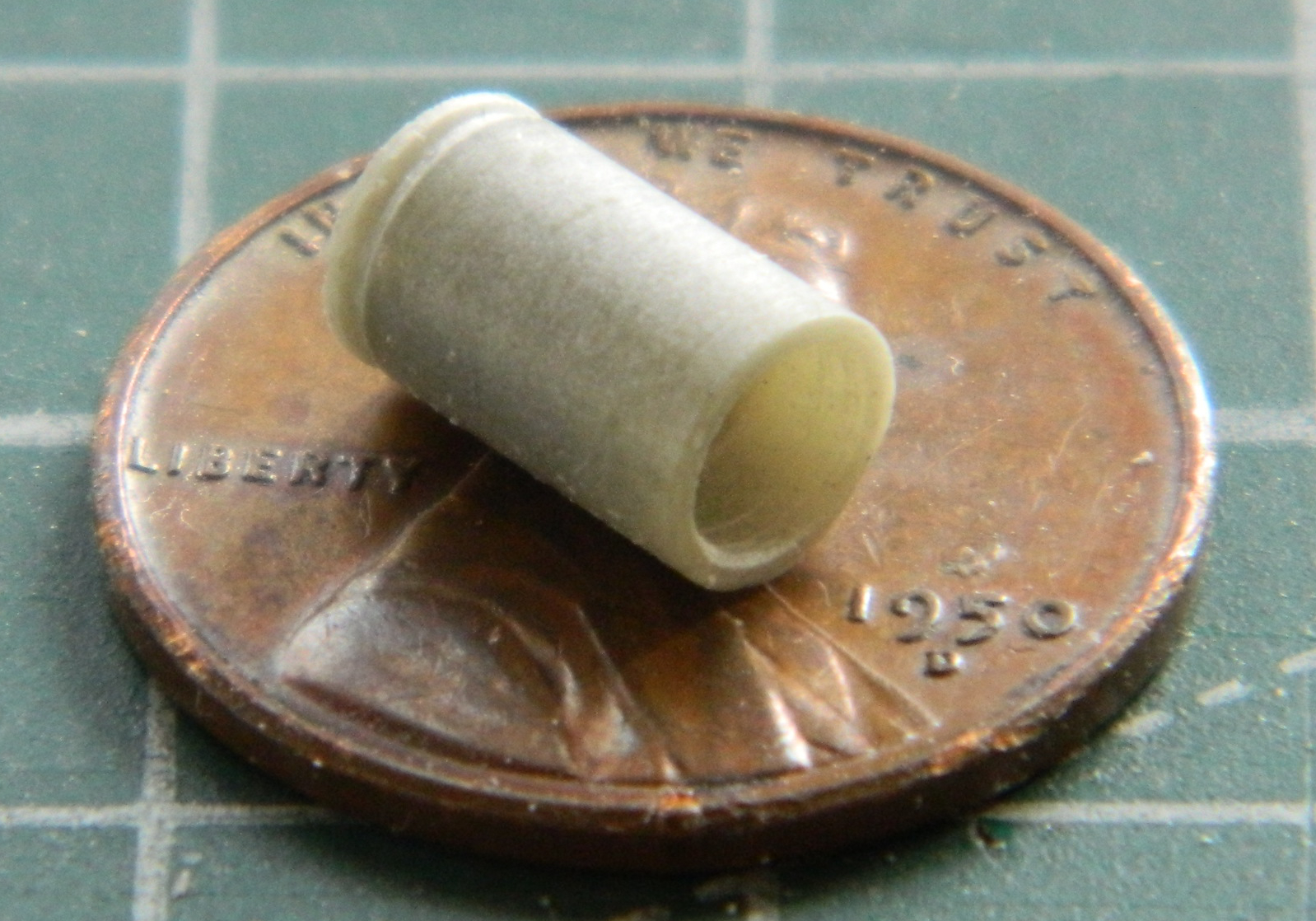

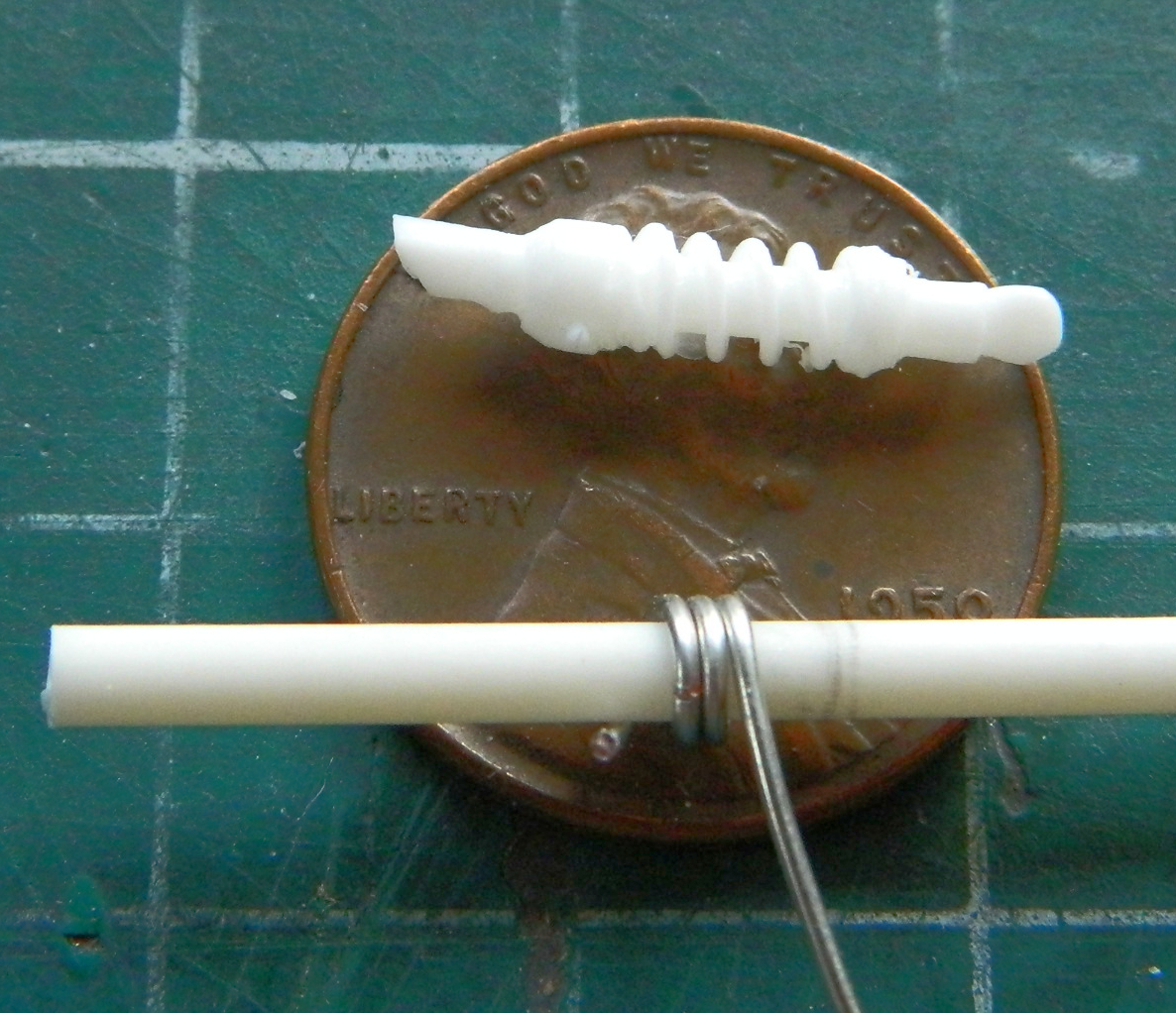

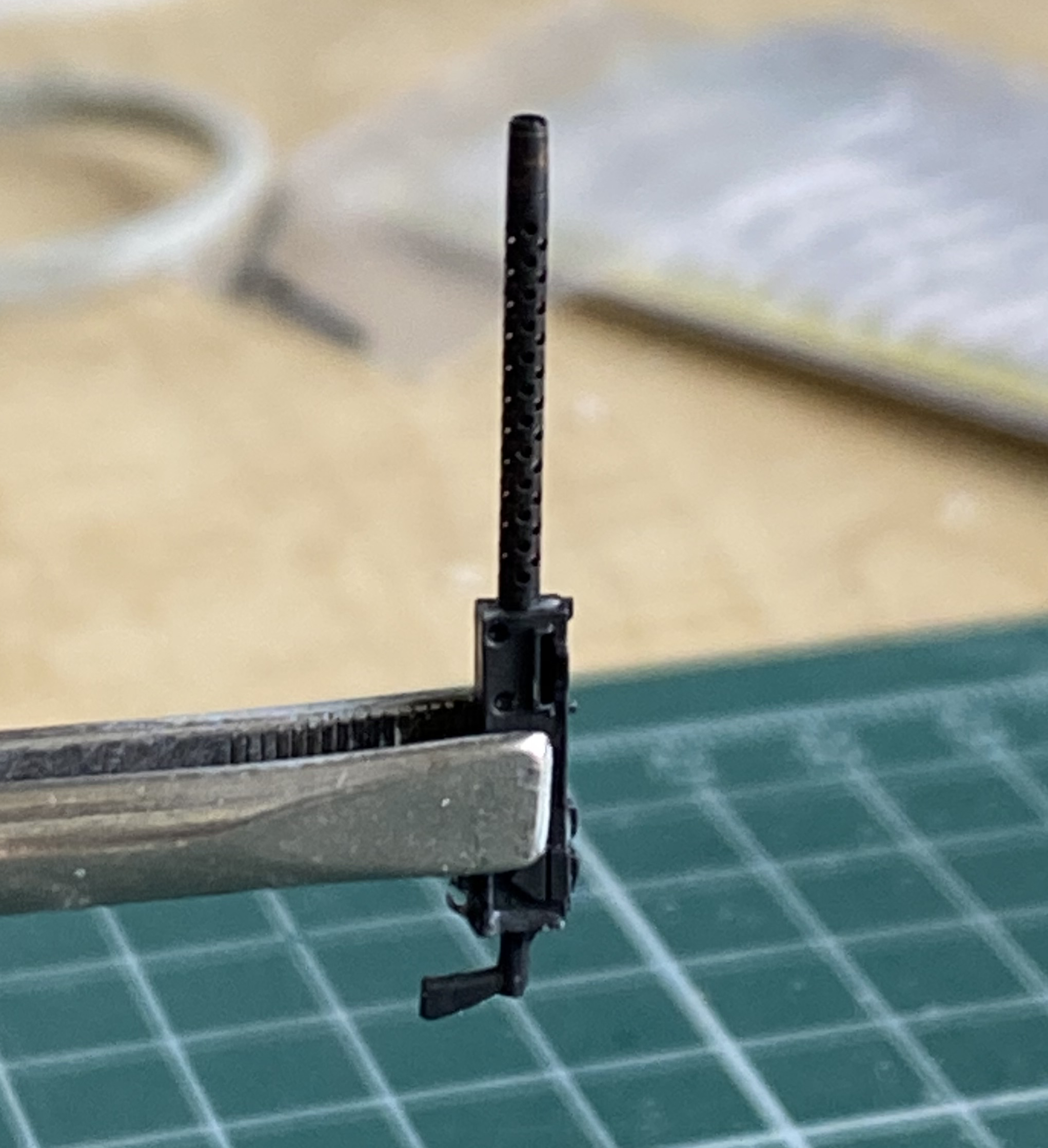

And just for a change, I thought I’d work on something really fiddly and annoying…getting the ignition wires conduits drilled out (to accept 0.010″ [.245mm] solder spark plug wires). Two of them, one for each engine:

You can see in the above photo where the bit broke through the side on a few (one is down near the bottom and there were a few others). Though annoying, it’s not a deal-ender. The breakouts will be filled with superglue and are really tiny. Once I’d done both conduits, they were glued to the engines and then I started adding the plug wires:

And in a curiously funny reveal, it wasn’t until I’d edited the photos a couple of hours ago that I noticed that I’d missed one wire…on each engine! Those were just taken care of. ::facepalm:: This is how I can see such TINY things with such OLD eyes:

While dry-fitting things, the exhaust stacks jumped up into my attention and since it was an easy fix, the fact that they’re way too thick, I just drilled them out to a less inappropriate wall thickness. Check the difference of the bottom six. The three on the right have been drilled out:

This:

Isn’t as good as this:

Having dry-fitted the engine nacelle together, I saw that in the area right behind the engine yet inside the nacelle, would be a good place to fit lead! It’s in front of where the main gear touches the surface and in a space where, once painted flat black, would probably never be seen. I have my big anvil downstairs in the basement so I took one nacelle and the bag of .36 caliber balls (because I more of them than the .44 caliber balls) downstairs.

Pro modeling tip: If it has a pulse, do NOT wail on it with a hammer:

And of course I did that on the last of eight:

Since I’m still in stuffing mode, I started lining the cowlings with tungsten tape:

The above photo shows three layers of tape but since I had the room, I added one more. Then I weighed the engine and cowling together and came up with a total weight of 19.6g. Double that and I’ve added 39.2g. I wish that it was further forward for the mechanical advantage of leverage, but more is still more.

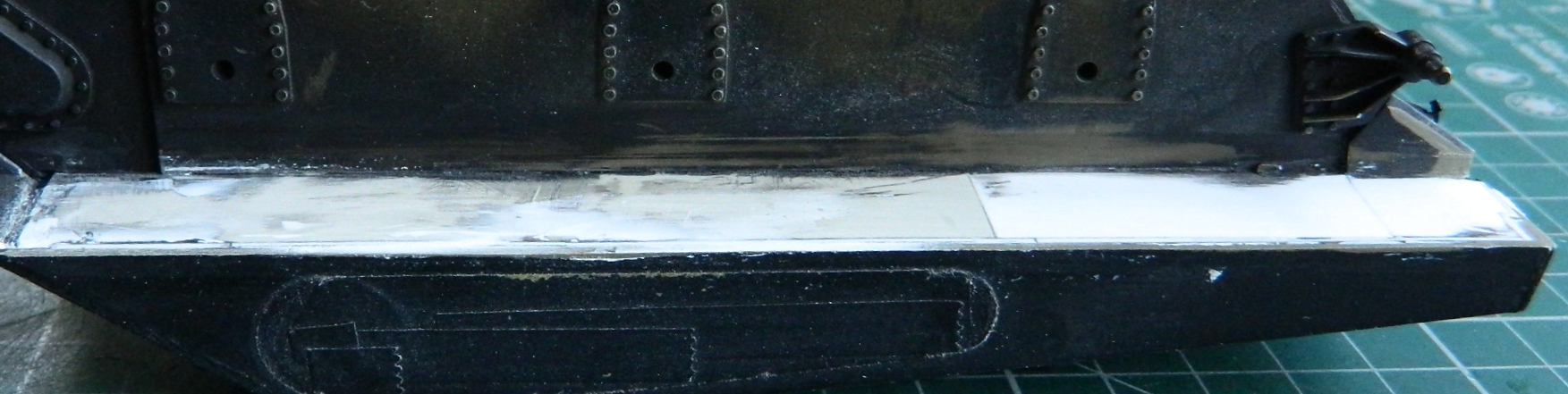

While manipulating the nacelles, I noticed that the landing gear openings aren’t exactly square at either the front or rear:

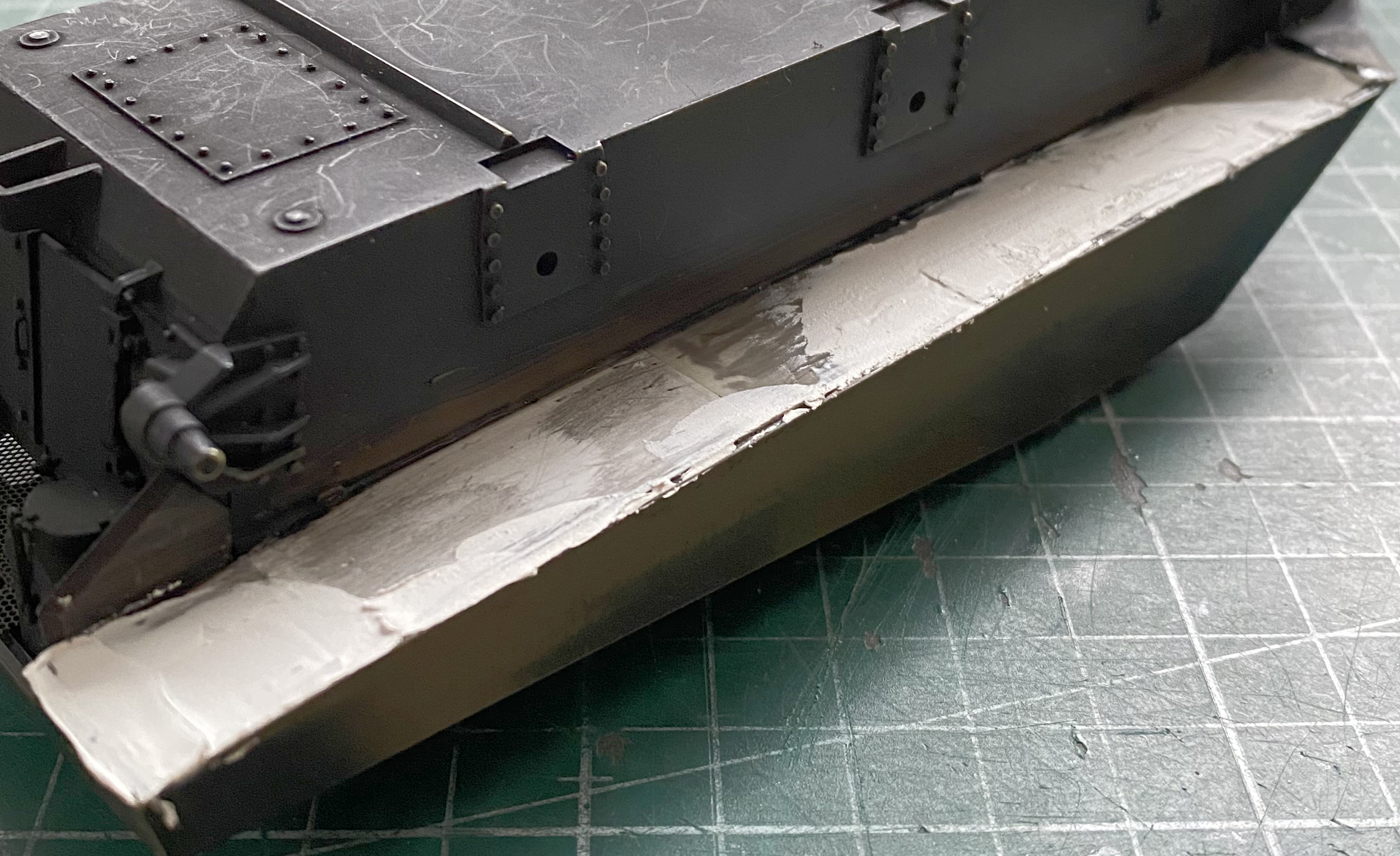

I fixed that by adding a bit of .020″ (.508mm) styrene scrap to the faces of the openings and let it sit overnight for the styrene cement to cure totally…twice, because the other side had the same problem:

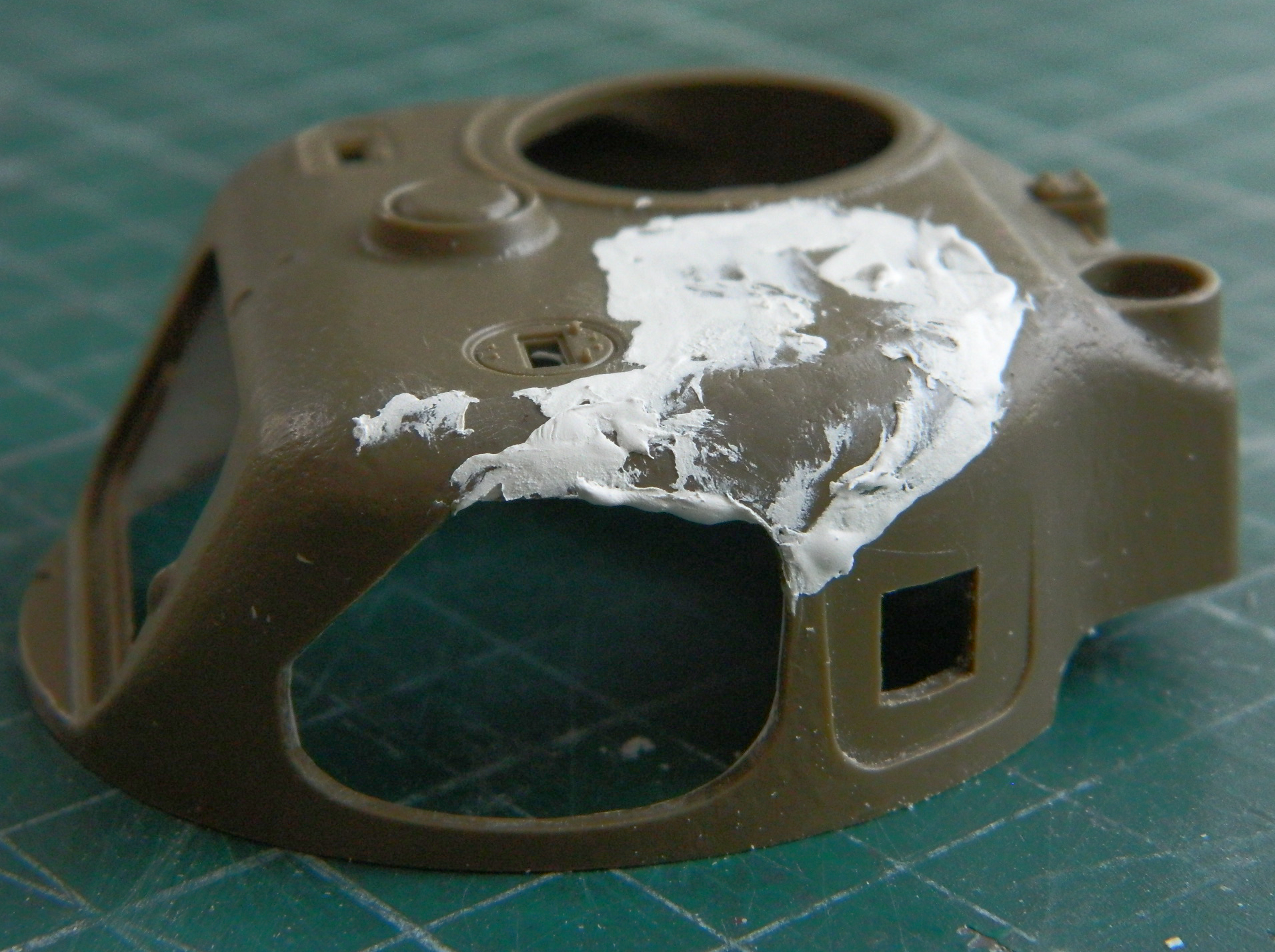

You’ll also note that the nacelle on the right in the above photo has had putty applied. It’s been applied to an area that’s supposed to be flat, not angled.

While they were sitting for the putty to harden, I turned my efforts to cleaning up the SAC metal landing gear struts. ::sighs:: I’m no stranger to working metal. I worked as a metal finisher in a couple of art-casting foundrys. Though working on aluminum, bronze, steel, and stainless steel requires different tools because of their respective hardnesses, working pot-metal (likely tin and antimony, but don’t quote me) is magnitudes worse.

I have a hypothesis (he humorously states as if he’s got just one) that all solutions create new problems. Often the strength of anything is also its liability. Pot-metal does not contradict this hypothesis. Its ability is that it’s soft and bends easily. Its liability is that IT’S SOFT AND BENDS EASILY. And since it’s also a metal, bending it too much introduces stress cracks and that leads to the sodding thing breaking off. So…after I broke the end of one of the main struts off, I got to deal with drilling out the metal, adding a pin (wire), and gluing it back together. Seamless.

Unfortunately I can’t say that about the parts themselves. It’s clear that the molds were taken from the kit parts. Asset: they’ll fit the kit about as well as any other kit part fits. Liability: minimal clean up was done before the molds were taken and the little that was done was poorly done. As you aircraft modelers are well aware of, there’s a portion of the landing gear that moves up and down (it’s called the oleo strut) and since it slides within a seal, that part of the landing gear is very shiny. The “poorly done” verdict was levied because the little clean up that was done was done on the shiny part. Badly. Badly enough that I’m going to cut the struts apart, all three of them, and replace the oleo with steel. For the nosewheel I’ll be using stainless steel welding rod, and for the mains I’ll be using part of a paperclip:

Zoom in on the oleo sections…you’ll see what I mean.

But those parts needed to be cleaned up so that’s what I’ve done (and as further support of my thesis, check out how thin the metal oleo is down near the bottom, and how thick the kit’s oleo is):

Yeah…drilling all that out. We’ll see how that worked (or didn’t) next month.

F7F-3 (AMT/Italeri) A Brief Overview

The F7F-3 Tigercat was the Navy’s first twin-engine fighter as well as being its first tricycle landing gear aircraft. Design and development time (the prototype didn’t fly until November 3, 1943) kept it from seeing duty during WWII and most of the -3’s 364 airframes that were built at the end of production in 1946 were given to the Marines. Most of the -3s were converted to either a photo-recon variant, the -3P, or a night fighter, the -3N with the remainder of the -3s being used for training purposes.

Initial problems were pretty much designed in. The first problem was that the Tigercat was too big and heavy for any carrier class smaller than the Midway class. (Its undercarriage, airframe, and tailhook needed to beefed up.) That restricted where and when it could be deployed. It seems its major flaw was that it didn’t spin well. Ah…yeah…maybe it spun TOO well, because it was discovered that after four spins there was no recovery possible. VJ day also meant that the Tigercat was a tool for a job that didn’t need it anymore. It was still big, really fast (70mph faster than the F6F Hellcat), had a range of 1300 miles, and being armed with four fifty caliber machine guns and four twenty millimeter cannons, as well as carrying two 1000lb bombs underwing or a Mk13 aerial torpedo under the fuselage meant that it would smite with a big hammer…but smite what?

Then there was the lousy timing (from the Tigercat’s position) of its introduction. About this time, air arms and aircraft designers were invested in a new bit of kit that is also called “jet engines.” (Things like the Grumman F9F Panther.)

That all meant that once the final peace treaty of WWII was signed, there wasn’t much will expended on (and probably less money) spent on the F7F.

When the Korean War kicked off, we had a lot of propeller driven aircraft that had made their bones in WWII on hand. P-51 Mustangs, F4FU Corsairs , AD-1 Skyraiders, all of which were pressed into immediate service in the Korean skies. No need for F7Fs…

However.

The F7F-3N night-fighter variant carried the SCR-720 radar with a protruding fairing under the nose and this time the second crewman had a job! He operated the radar and his location was in a second cockpit behind the pilot.

The -3N was ferried arrived aboard the carrier Cape Esperance to Japan and VMF (M)-542 Marine night fighters which brought them to Inchon. During the opening weeks of that war, the North Korean pilots flew harassment missions at night in biplanes, the PO2. Tigercats of Marine Night-Fighter Squadrons VMF(N)-542 and -513 were credited with two kills. The F7F’s combat role was brief as the turbojet F3D Skynight soon replaced it in the land-based night-fighter role, though through 1952, F7F-3P and -3N were used in support of B-29s (which were flying night missions because of the high loss rate of daytime bombing operations).

The F7F-3P was the photo-recon variant and carried five cameras. It also had a second cockpit for the camera “operator.” But since the pilot aimed and triggered the cameras, the camera operator was unneeded and his position saw the canopy over it removed and fared over with sheet metal.

Any pilot accounts I’ve read are favorable. Pilots liked that it was comfortable, robust, smooth, and powerful.

Crankenstein – 1/25 Scale Kitbash Build Paused

For personal reasons I’m suspending this build for now and going to do something else for a while.

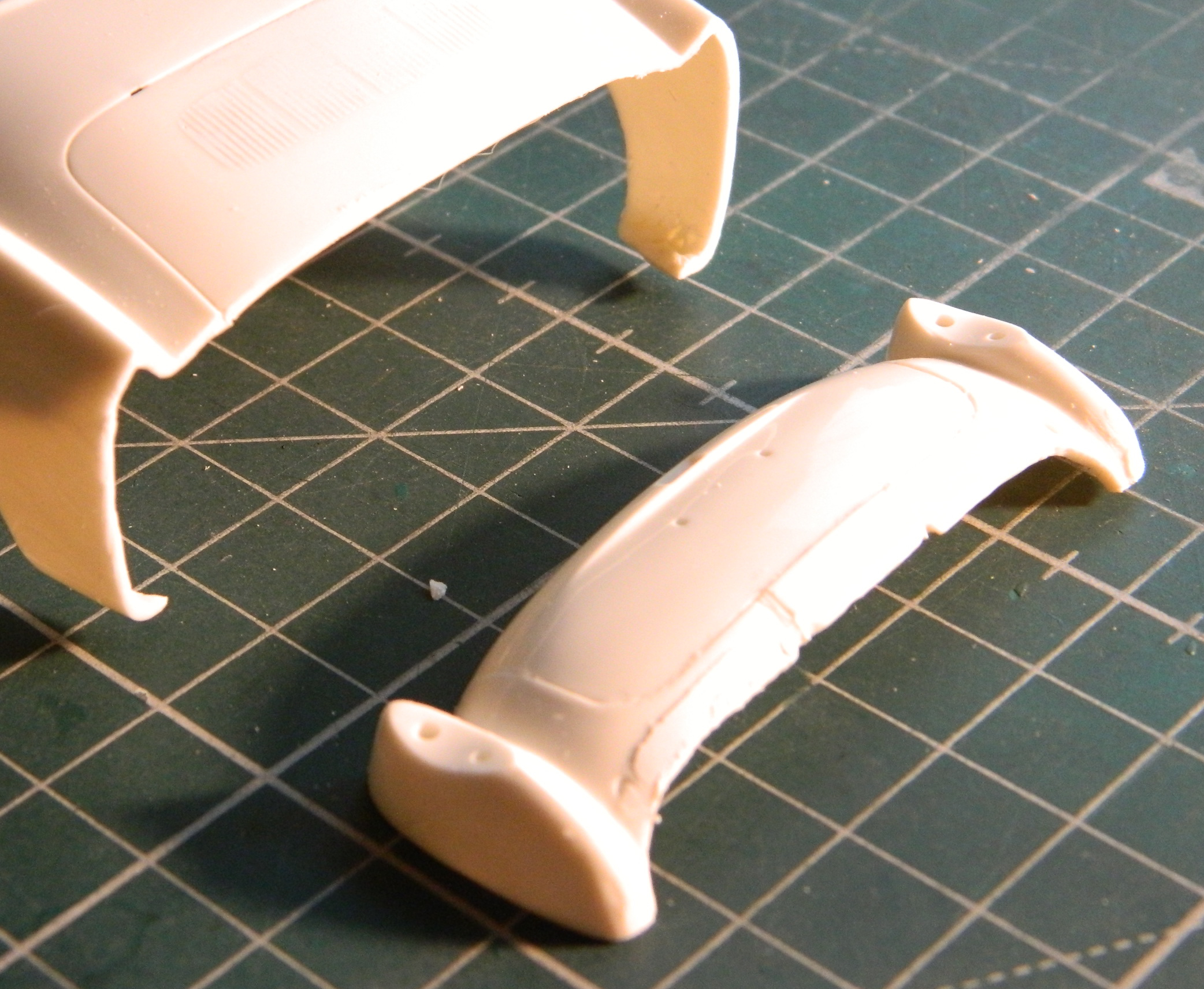

Crankenstein – 1/25 Scale Kitbash Build #3 Extending the Body and Coming to a New Understanding of the Scope of This

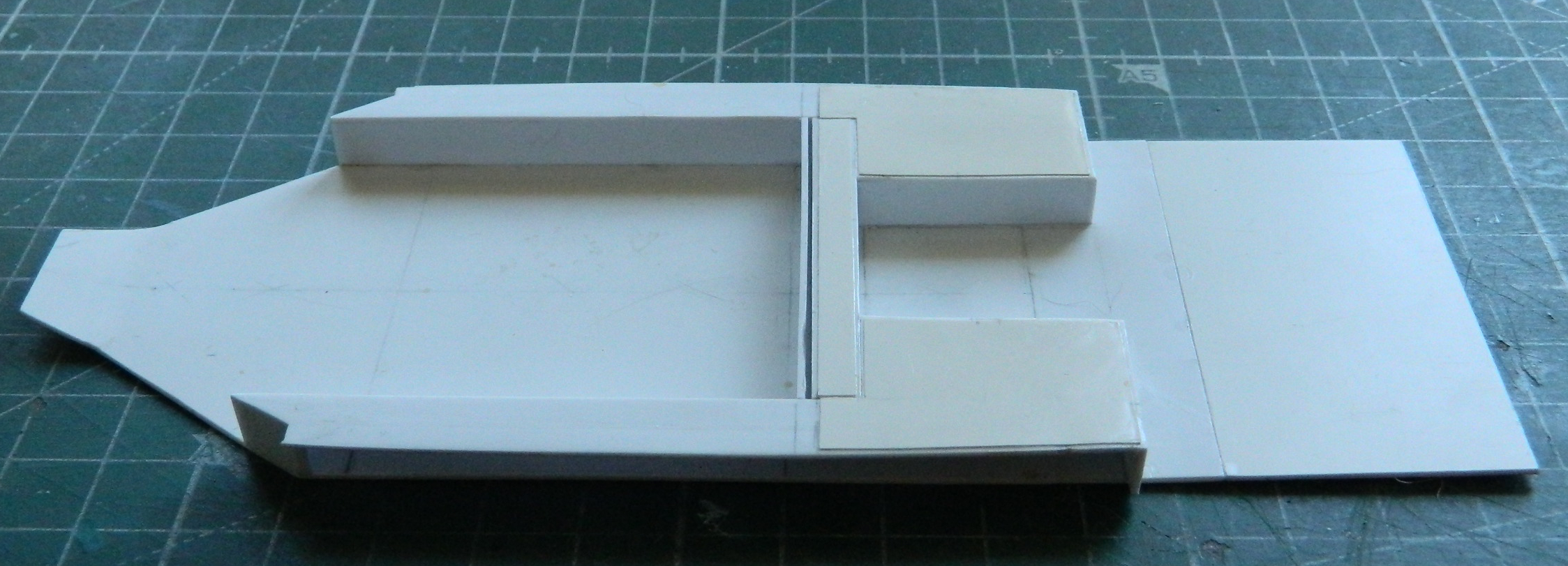

This month’s work was mostly bodywork, specifically coming to the realization that I really am going to have to extend the rear coachwork. This awareness was finalized as a plan once I had enough constructed to lessen the degree of guesswork about where the power-train goes, which determines where the axles go, leading to the understanding of where the wheels and tires will be and thus the rear fender flares. Initially I’d thought that I could just do a speed-hump (no…not at my age I can’t) and cover the rear of the transaxle where it protrudes beyond the body. I added a bit of .040″ (1.016mm) bracing so that the bodywork would be dimensionally stable:

But once I estimated the location of the rear wheels, and subsequently the fender flares, I realized that the rear of the flares extended well past the rear of the body and would end up removing the sense of “Karman-Ghia” that I’m trying not to obliterate:

The brace was removed and the section of body that I’d removed was glued back into place.

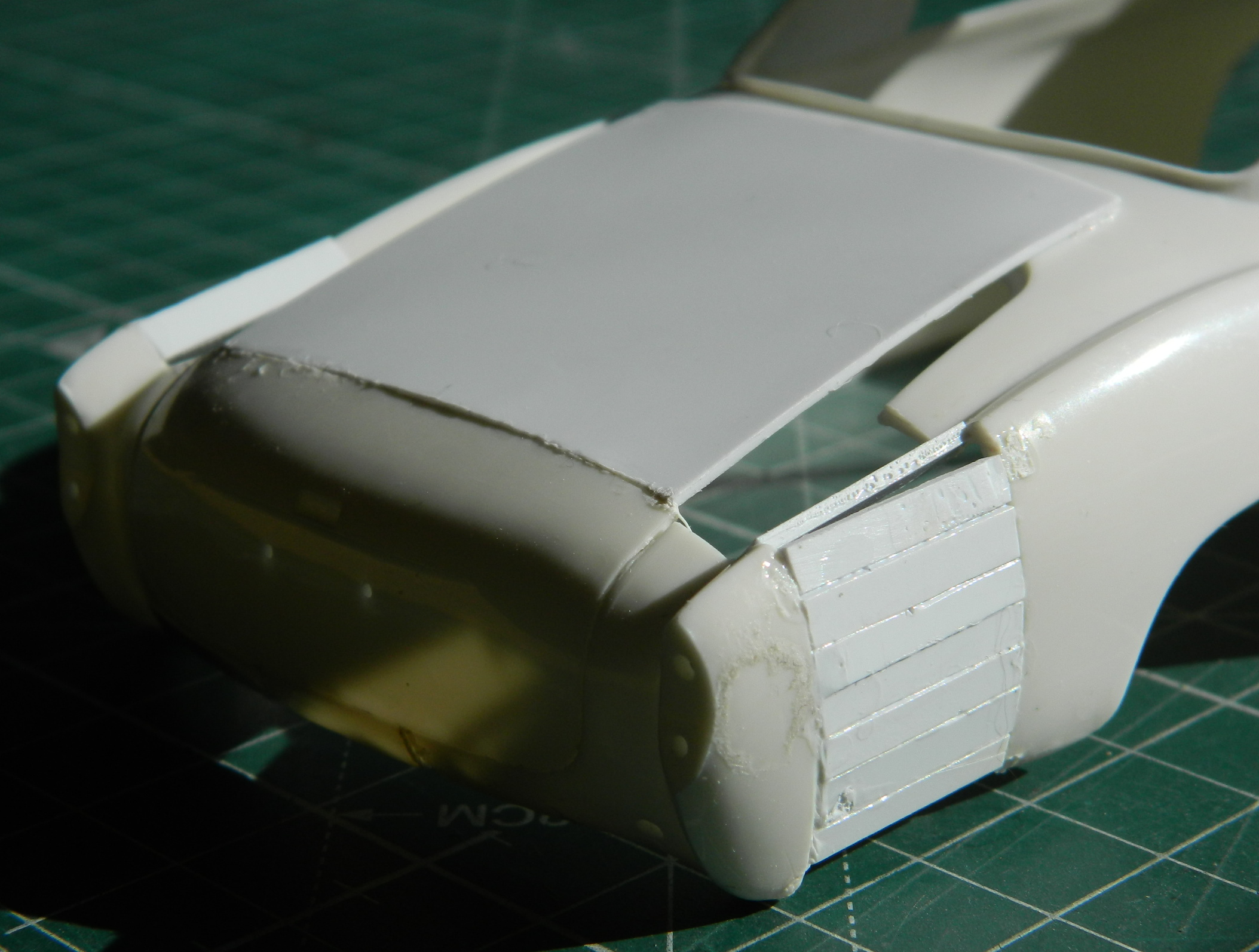

I had initially considered making the cut much further forward, and I’d also considered making a couple (or more) cuts to blend the compound curves. I decided that I was, once again, overcomplicating things. Since I just need the back of the bodywork to extend past the end of the transaxle, I decided I’d just cut the end of the body off. I glued the stock engine cover in place for structural stability, only gluing the part that would be removed with the body (because as this point I still have the notion of having the former engine cover hinged separately from the rest of the hinged rear body to have a small load-carrying space that could be accessed without having to open the whole back of the car to get to it). I laid out the line and made the cut:

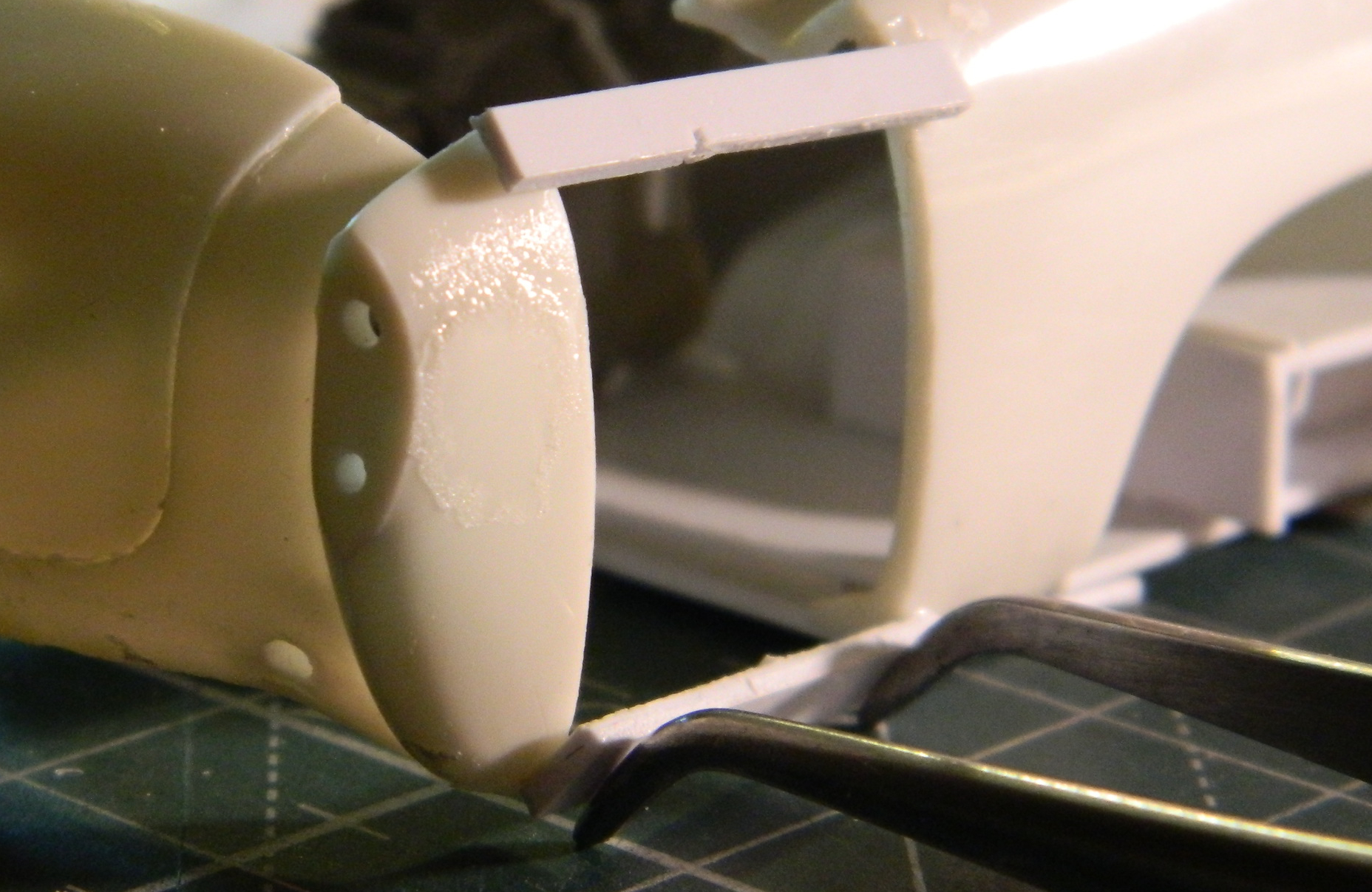

Not only did I move the section that was cut off back 5/8″ (15.88mm), I also moved it down in order to maintain the arc of the upper curves of the rear fenders. Once I figured out where I wanted it, I added .040″ (1.016mm) braces to hold it there (and managed to superglue my thumb to the rear of the fender, as you can see in the photos):

Having positioned the rear of the body, I checked to see if I could just add a piece of flat styrene sheet for the upper body. Looks like I can:

That obviously left large areas that need to be filled. Rather than drive myself crazy(er) by trying to make a single-piece fill section, I opted to use more .040″ (1.016mm) strips as structural filler as well as gluing a flat piece of the same thickness styrene on top. For the ridge at the top of the fenders, I filled the odd shaped gap with .080″ (2.032mm) scrap:

l used more .040″ (1.016mm) to fill the gaps on either side of the top addition and then roughly sanded the additions to shape as well as filling the stock wheel openings using .020″ (.508mm):

Much putty was needed to smooth the surfaces. Rather than lay down several layers of putty putty, I opted instead to use Aves Apoxie Sculpt (great stuff if you ever need a structural filler!) and waited overnight for it to harden. The join of the top of the rear deck and the side sections started to show gaps after minimal sanding so I added the Apoxie Sculpt there as well:

Since the rear of the body will be hinged, I needed to add Apoxie Sculpt inside as well:

After letting the putty cure overnight, I used my Dremel to roughly shape the putty (and created a metric TON of dust):

The first shaping was done with a file:

Then it was all sanded. I started with 220 grit and went through the grades up to 2000 grit:

My goal of creating a gradual curve on top of the fenders worked well:

I knew as I was doing all of this that a large area would be cut away on both sides to accommodate the wheels/tires. I also knew that I was going to have to fit the fender flares to the body so I wanted the surfaces to be properly shaped before I started that.

Though it looked odd at first, I rather like the extended body:

To know where the openings need to be cut out, I needed to know where the wheels/tires would be more accurately. Since it’s the engine/transaxle that determine where the rear wheels/tires will be, I needed something better than tape or white glue to determine where the engine will sit. The next task was to build the engine mounts so that I could dry-fit the engine/transaxle to where it will be attached. I knew that not only were these parts need to be sturdy enough to handle being moved around a lot, using .020″ (.508mm) styrene wouldn’t provide much gluing surface, so I reinforced the joins with Evergreen’s L-shaped extrusions:

These parts did what I want them to, locate the engine, but they’re too clunky. I’ll make another set of them later:

I also needed to fit the rear engine and suspension mount so that I have the angles for the driveshafts at the correct height. While that part is still free and the surface of it easily accessed, there was something I needed to fix first. For whatever reason, the resin copy has these two depressions that shouldn’t be there :

Once I added the putty (deciding to finish the surface later), I was able to put the engine where it will end up being (the plastic underneath the transaxle is just there as a spacer to maintain the correct height):

I wanted to determine the ride height of the car. Seeing as it’s a street car, it couldn’t be as low as a custom or race car. The streets are much rougher on a car than a track (or trailer), having things like potholes, speed-bumps, driveways with steep approaches, and all the other wonderful things that street cars have to cope with. I wanted to shim the car and monocoque at a ride height I thought to be realistic. For that I used quarters and now I call this my “seventy-five cent clearance” because three quarters gave me just what I wanted, or about 6″ (152.4mm) scale inches:

With ride height figured out, I dry-fit the engine, aligned things, and traced around the tire to determine the size, shape, and placement of the rear wheel openings. I did this while both the body and the monocoque were sitting flat on the bench instead of at ride height to allow for suspension compression:

Once the putty had cured, I sanded down the putty inside the bodywork:

At this point there has been a lot of sanding of plastic that wasn’t too thick to start with. I wanted to check how thick or thin it was, especially where the seams are. I held the body up to a bright light (the sun) to see where it was getting too thin:

Answer…where the plastic lets the most light through. I knew that I was going to have to thicken this entire area a bit and decided that there was no point to waiting. I laid down strips of .020″ (.508mm) scrap styrene and then another coat of putty:

While that was curing, I did a little work on the monocoque which gave me more room for fuel tanks. I haven’t done the numbers yet but I estimate that I’m probably at the 25 gallon (94.6L) target, perhaps more, and now that I have a better idea of how long the chassis needs to be, I added an extension to the rear and made a less-clunky set of engine mounts:

Having ascertained where things go, it’s time to put some things there. The rear fender flares. If I could design a body for an inveterate modeler, I’d design someone with variable-magnification eyes and four arms so that I could have four hands. I think the second pair of hands would be really small for handling really small parts. Since my body doesn’t have those features (or many other ones lost over the decades), I figure out how to make do with what’s left after the Sands of Time have scoured thoroughly.

I need to hold the Bug fenders in place while holding the body in place while outlining where I (possibly) need to cut the Bug fenders. Lacking the genetic and physical modifications that I so ardently desire (hmm…buying shirts could pose another challenge), I used a lump of Plasticine to hold the fender in place so that I could mark it:

Once marked (sorta), the cutting, filing, sanding, and fitting began (double-sided tape stuck the flare to the body to allow me to step back and look at how it went):

Well, it didn’t go as I’d hoped (but expected) and some plastic had to be added back and I used various thicknesses of scrap to do that:

This was followed by more sanding, scraping, and filing. Eventually I got things close enough so that I was confident that the Apoxie Sculpt could bring it home:

The I got to do it again on the other side, hopefully (more on that shortly) matching what I had just done. This process was repeated on the other side and all of the putty was filed and sanded:

And…no. I didn’t get both sides identical. I also didn’t notice the difference immediately (the second flare was a bit wider than the first). I worked (snapped, more accurately) the forward half of the second flare loose, figured out how much I had to remove, and started cutting:

I thought it would be easier if I took a little bit more off than I needed because in this manner I could adjust the width easier (and this time I was correct…I’m not getting accustomed to that and neither should you):

That almost did it. Once the front of the flare was narrowed, it showed that the rear of it was also too wide (go figure) and I took care of that in the same manner. Finally satisfied that the flares were as close to identical as I could make them, more epoxy putty was applied. Then the putty was ground, filed, and sanded:

My original intent was to be able to use what had been the headlight sockets as brake lights and the original brake light locations used as backup lights instead. Since lengthening the body meant that the rears of the fender flares wouldn’t match up with the rear of the car’s body, that notion got tossed. Instead I’ll be using what’s left of the headlight sockets as vents to allow air that gets pulled into the engine bay to have an easy exit.

I’m stopping (briefly, I hope) at this point because though I know what I have to do, I’ve less than no idea as to what the build sequence should (and will) be. I think what I’ll do instead is to add the front fender flares while the BitB work on it and hopefully come up with a workable plan because right now I am utterly bereft of having one.

Crankenstein – 1/25 Scale Kitbash Build #2 Starting to Figure Out Where Things Go…and Wondering How to Get There From Here

Since I need the engine/transaxle to define where the interior can fit and where the body needs to be modified, I started this month’s work by removing the bellhousing from the engine. I’d started to use a saw but on that particular morning my hands weren’t as steady as the job required. I took out the Dremel and made a dusty mess of things:

I used a flat file to true up the end of the block. I figured that I’d probably need an adapter plate to mate engine and transaxle. For that I used .040″ (1.016mm) styrene. I countersunk holes to match the bolt locations at the back of the block and stuffed tiny bolts into them and then glued the transaxle to it. I trimmed excess plastic away (and added some where I needed more):

Since the location of the power train determines so much of what happens with this build, I was eager to see if I was going to have enough room for it:

And it doesn’t look like it. Well, not unless I modify the body to fit it, and since there’s going to be a lot of body modifications anyway, I see this as another bucket of sand on the beach in terms of effort/work.

At the front of the engine and there a gap between the timing belt cover and front of the oil pan. I slid a bit of styrene scrap in and filled the odd gaps with superglue:

The rear of the body will be detached so that it can be opened. The B pillar is quite narrow. With the plug on the left side replacing the window, I know I’ll have enough to work with on that side. On the right side I had to add something large enough to split. I used .020″ (.508mm) for that, using flat-jawed alligator (toothless alligator?) clips to keep things aligned:

While the glue was curing, I added a disc to the front of the timing cover to provide the harmonic balancer that hadn’t been molded on:

The bellhousing that’s attached to the ZF transaxle doesn’t have the provision to mount a Chevy starter motor. I built one from Aves Apoxie Sculpt…:

…and attached it to the bellhousing:

When I realized that I hadn’t quite added enough where I need it, I mixed up more and fixed that. (This material is very versatile and adding new material to already-cured material is no problem and it bonds well enough to be indistinguishable from the already-cured material…and yes…I plugged the bubble on the end of the solenoid.):

Continuing with the theme of a street-legal car used on the streets, I live in New York State. Summers can get quite roasting what with 90F-100F (32C-37.75C) days and relative humidity within the same range. Hot and sticky. At this point of the build, though I intend for the windows to be operable, I’m not entirely sure they will be. In order for this not to be a mobile over-powered bread oven, air-conditioning stops being optional. Because there is more than enough work to do yet, I went online to find an a/c compressor and the only one I found was unacceptable. That means I have to make one.

I have a few sets of AM pulleys and used one for the compressor. The only styrene tubing I have is either too little or too large. Once again I used Apoxie Sculpt. I mixed it (it’s a two-part compound mixed 50/50) and rolled out a rope of it. After it cured overnight, I took the straightest section of it, chucked it into my bench-top lathe, and turned it to match the pulley’s diameter and then drilled out on end of it to socket the back of the pulley into it:

I punched a couple of discs from scrap using .020″ (.508mm) for the face detail and .010″ (.254mm) for the clutch face (getting the hole in the thin disc took a couple of tries to get correctly…punching the hole first, centering what will become the disc):

I made the mounts from .030″ (.762mm), making the required holes for the compressor and mounting bolts:

I failed to notice that the front mounts have longer lugs than the rear. Rather than redo the part, I added little scraps that I’d removed in error to it:

The last things I added were the wiring (two twisted strands of 40 gauge wire and sandwiched those between two pieces of .005″ (.127mm) scrap to replicate the connectors, a couple of small plastic bolt heads, and two resin nuts for the Freon line connections (sourced from resin AM bits of 1/35 scale bolts used to hold trunion caps onto suspension bogeys of a Sherman):

With the compressor built, I need a way to attach it to the engine. Generally, the compressor is attached to the upper left corner of the engine. Unsure as to whether or not that location would interfere with the exhaust headers I’ve yet to build, I decided to make a custom mount at the lower left of the engine and for that I need mounting brackets. Detail Master makes a number of nice PE bits:

The problem with these parts is the Detail Master parts are only .003″ (.076mm) thick. Funny. I used the word “thick” because they are not thick at all and turned out to be far too flimsy to use. Instead I decided to trace them onto .005″ (.127mm) copper shim stock. My first try, as is typical for me, went well (I used hemostats as a clamp so that I could use a needle to trace the part):

Also typical for me, the next couple of attempts were horribly unusable. Rather than keep trying the same method, I used Tamiya masking tape to trace onto instead of the copper. That worked better and, after filing/sanding (no pictures of which I’d taken), ended up with something I could use:

I used a really tiny bit to drill holes and then cut away the material between the holes to get a slot:

Well…something slot-ish. Copper is a relatively soft metal. I bent back the shape to expose the serrated edge inside the curve and filed/sanded it smooth. That worked well enough to do the same thing with the outside of the curve:

Yes, it’s a little bit thick but subsequent filing/sanding thinned it out more correctly:

Needing a break from SODDING SMALL PARTS, I turned my efforts back to the body (unlike the decrepit wreck I inhabit). For whatever reason, the 3M Acrylic Putty was flat-spotted after sanding…like all over the place. None of the photos I took really show the problem well, this is the best of the lot:

I used a scriber to scrape all the putty out and redid the unneeded panel lines with stretched sprue:

And in this photo, I filled a poorly scribed line while I was gluing sprue down:

That seems to have worked better (later on a coat of medium gray will reveal if I’d been successful):

And completely by chance (because I wasn’t really checking for it), I discovered that the body is twisted and doesn’t sit flat. Everywhere else on the body is in contact with the cutting mat except this area:

I tried a hairdrier on high setting. I tried boiling water. Nothing worked. Then I decided to use a mode that’s worked for (and too often against) me over the decades. BFMI. Brute Force and Massive Ignorance. I grabbed the body and just TWISTED IT. It took a few attempts but now it sits flat and didn’t break:

With the water pump and pulleys on the engine, now that I know what real estate is needed, I did a closer inspection of engine placement. With the power train at its furthest rearward point, it sits too far forward:

In order for the front of the engine to be back far enough to where I want it to be, a bit of the transaxle sticks out of the back:

So not only will the rear wheel openings need to be moved, I was thinking that the whole body would need to be stretched. I started playing around with that notion, laying out lines that I thought would involve the least amount of work:

Note that I’m not concerned at all about having to move the wheel wells. I’m going to be adding fender flares so those areas are going to be reworked anyway. I just don’t want the rear of the transaxle flapping out in the breeze. I could have added lots more pictures of the various notions I investigated (Mssr. Goldberg would have been awestruck). Each “solution” created more problems, none of which was I remotely interested in dealing with. I pulled the tape off and went to bed.

When I awoke (and properly, necessarily, caffeinated), I found myself wondering if I’d been a German engineer in my previous life. I don’t need to stretch the whole back of the body. And I didn’t want to stretch the whole back of the body. It wasn’t because of the amount of work that would require. If that bothered me, I wouldn’t be doing this. What I wanted was a way for the curves to move smoothly from the rear of the back window to the rear of the car…and I couldn’t see how to do it. What I needed was a way to cover the rear transaxle. Just that.

My first thought (in a German engineer sort of way) was to use the epoxy putty to form a buck and then vacuform a cover (I put aluminum foil over the body to keep the putty from bonding to it):

While that was curing, I started working on the belly pan, which is what would form the floor of a semi-monocoque frame. My first attempt was to just trace the kit’s belly-pan onto a sheet of .030″ (.762mm) styrene. I thought that would fit but it didn’t. I spent far longer than I should have on making it fit (chasing pencil lines across the styrene, erasing, doing it again, erasing it again) until I realized that it just wasn’t working. I checked the fit of the kit’s belly-pan again and it fit. Okay, that means that I’m somehow screwing up the tracing process. I covered the belly-pan with masking tape, trimmed it, and took the tape template from the belly-pan and placed it onto the styrene, cutting around the tape with a scriber:

That was the starting point. It seemed that nothing was really square. But since I had the basic dimensions, I erased, measured, squared, erased some more, until finally I had something that didn’t contradict itself visually:

I dropped the body over the pan and checked the powertrain placement again. To get the engine placement where I want it, I am indeed going to have to deal with the transaxle fitment problem:

I’ll bridge that cross when I get to it…

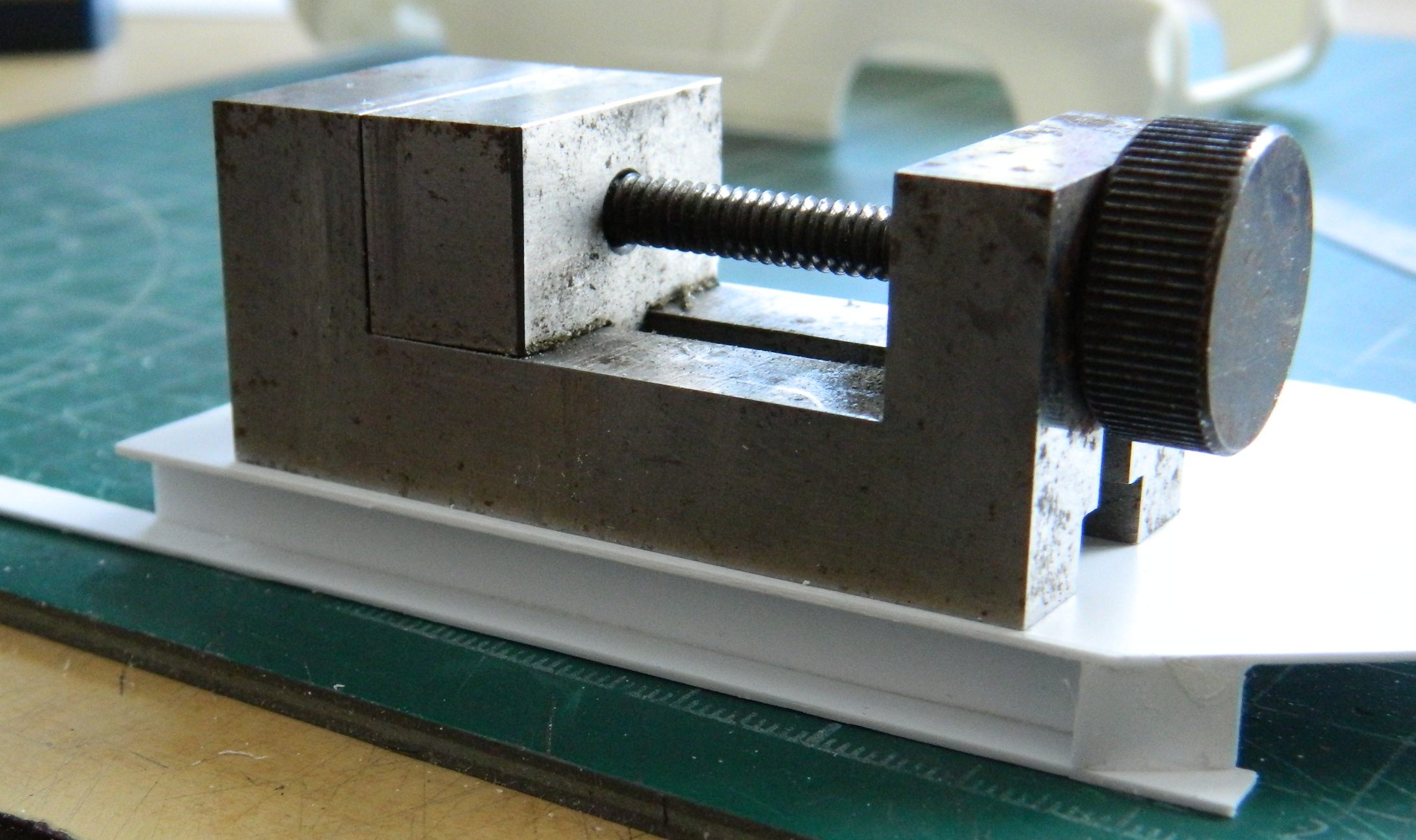

The reason I moved the bottoms of the doors upward was to have a space for sponson-mounted fuel cells. Best I get started on them. I used a milling vise as my 90-degree angle and used .030″ (.762mm) for the sides of them, using the lower edges of the doors as my gauge, the height of these are about 1mm below the opening:

Then I used the vise as a weight to hold the tops down firmly:

While those were setting up, I put the rear tires (resin parts from HRM, the same source for the ZF transaxle) roughly where they go longitudinally to get a very rough approximation of what I’d need from the fender flares:

It’s looking like about half that tire will stick out beyond the body. Also note how far back from the stock wheel opening it sits. And there is going to be substantial reshaping of the back of the car to accommodate it all. For fender flares, I’m going to use highly modified VW Bug fenders. Because of the taper to the rear of the rear Bug fenders, I’m going to put those on the front and connect them under the nose of the body and create the “cow-catcher” front spoiler so common at the time (and yes…I bought a VW Bug kit just to get the fenders):

I’m going to use the Bug’s front fenders on the rear:

Because of the amount of work and reshaping required, I’m waiting until I have the fenders fit and attached before I reconsider what I want to do about the transaxle sticking out. And because of the prominent headlight buckets, I’m going to transform those into the taillights. At some point I’m going to have to decide where I want the air that is sucked into…wait…did I tell you about the radiators? Now wouldn’t be a bad time to do that.

I’m not putting the radiators in front. I’m going to reshape the forward portions of the rear fender flares into scoops. Air inlets. Behind those inlets will be the radiators, which is why I’m discussing the radiators in plural. Racing cars that have front-mounted radiators have to deal with the volume of air introduced INto the car in some manner. The GT40s (and more than one of the 60s and 70s F1 cars) had two triangular-shaped outlets on top of the nose of the car with ducts to allow the introduction of all that air some way out. Air that comes in needs someplace to get out, otherwise odd and unwanted things happen when, and where, all that air gets compressed. A front-engined, front-radiated, car will start to get light in the nose at very high speeds because the air has no easy egress. It stuffs the engine compartment, meets the firewall, and gets out at the base of that firewall. The high-pressure air can get so high-pressured that it starts to lift the nose of the car. As it lifts the nose, the simple downforce created by the weight of the car is lessened and the nose rises. This allows more air under the car and, in addition to the air being stuffed into the engine compartment, the air allowed under the car as the nose punches through it lifts the nose even further. From the throttle-jockey’s perceptions, steering authority degrades into steering requests. Not pro-survival when the speed of the car is into triple digits and not merely because there aren’t tires on the roof.

Putting the radiators towards the rear of the car mitigates the lifting effect of all the above. But the air still needs to get out. It will find a way out, but with a car possessing a full belly-pan, lots of drag is the result because the air can’t simply force its way out from under the body. If you notice Group 7 cars from the 60s and 70s, almost all of them (including the GT40s) had screen panels at the rear so that the air has SOMEplace else to go and an easier way to get there.

There. Now I’ve mentioned the radiators. It’s not unlikely I’ll mention them again later on.

Now that the basic structure of the sponson tanks has been blocked in, I have to get them to fit the inside of the body. I did it by placing the body over the monocoque and gluing (lightly, I mistakenly thought) blocks to the top of the sponsons and up against the body:

Then I added strips of .030″ (.762mm) to that width:

Once that glue cured, I added scraps of the same thickness under the seam. These extensions are wider than the bottom of the body and with the many, many, on-and-offs ahead for dry-fitting, I’d really rather that they didn’t snap off:

While those were curing (both sides), I used the scriber and razor saw to remove the Bug fenders. Curious being that I am, I wanted to get a notion as to how much work was going to be needed to get these to go from detached fenders to solidly attached fender flares. In short…LOTS:

Both sets of fenders are roughly where they need to be. In looking at the rear, I can see that the back of this engine-sled isn’t going to look very Ghia-ish. Since I’ll be using the headlight buckets for brake lights, if the stock taillight positions are even visible after all the surgery, that would be a good place for backup lights. For certain, though, I’ll have no shortage of options for where the exits for air could be!

Mistakes teach us. I’ve learned a lot. The implication is that I make lots of mistakes…and that is true. Here comes another learning opportunity…

I’d seen a YouTube video (the name of the channel is “Model Car Muse”) where the content-creator used a woodburning tool to weld plastic (see the episode “Scale Model Body Modification Without Filler or Glue”). I decided that, since I’d been a metal finisher at art casting foundries, I wasn’t unfamiliar with using welding to fill a hole. I’d often had to fix a casting where something went very wrong with a section that in turn had to be excised and rebuilt using welding. There’s a big hole where there shouldn’t be one, so I went around the edges of the hole laying in welding bead until the hole wasn’t a hole anymore. I thought that I’d try that with styrene! My experiment with this was building up the underside of the rear of the body so that I could bring the belly-pan to meet it. I used a woodburning tool:

I then cut some sprue from the kit to use as “welding rod,” figuring that the same plastic as the body would probably be visually indistinct once it had been filed and sanded to shape. Then I started melting plastic (the engine cover is just tacked into place so that the body would be dimensionally stable):

Well…it worked, sort of. I discovered some things in this attempt. First, just like metal, cast plastic isn’t as dense as welded plastic. Welded plastic is HARD. I’d thought that being plastic, styrene cement would adhere to it, and it does, sort of…just not to the surface after being melted. The surface has to be ground/filed/sanded away and then the cement will work. Sort of. A large clamping force was needed and the resultant joint easily snapped. These sections of the body are compound curves (he says as if the remainder of the body wasn’t) and getting each side identical IS A BITCH. So the conclusion is that yes…welding plastic with a woodburning tool “works.” In this application it doesn’t work well enough to justify the large degree of work and fettling required. So I snapped them off and roughly cleaned up what was left. I can see a use for it down the line, just not here for this.

Moving on…

Once the glue had cured on the sponson extensions, dry-fitting showed gaps. I used .010″ (.254mm) and .005″ (.157mm) styrene scraps to fill the gaps between the edges of the extensions and the inside of the body:

Then I noticed that the belly-pan had gaps at the edges. Though not snug to begin with, I suspect that this had been exacerbated by shimming the sides of the extensions which pushed the sides of the body slightly outward. Again, with all of the dry-fitting ahead in mind, I decided to shim the edges of the belly-pan instead of all the on and off needed to fit the sponson extensions better:

I knew when I made the belly-pan that it was too short and would need to be lengthened, so I attended to that:

With the sponsons at this stage, they will also need to be lengthened. Before I can do that, I need to know exactly where the wheel openings are going to be. Before I can do that, I have to build more inner structure so that I can precisely determine where the powertrain is going to be, so the sponsons will be extended once I have made that determination. However, one of my goals is for there to be a minimum of 25 gallons fuel capacity. I took the measurements, converted to full-scale numbers, and determined how many of gallons the volume of these sponsons were. 11 gallons (41.64 liters) combined. In the above photo, there is a rectangle drawn just above where the pan has been extended. This is the space for the engine (considering tuneups, maintenance, etc. I would need space to get at the work). The space to either side can be additional fuel tanks! I haven’t done the numbers and conversions yet, waiting until they’re done before I drive myself to drink (any excuse, y’know) getting to the fuel capacity of them.

Torque would be a major concern if this was an actual car. The two forward lines drawn across the pan delineate where the doors are, which in turn delineates where the seats go, and so forth. I broke out the Mk I Eyecrometer and determined where I wanted the partition between the people space and engine space to be. The forward crosspiece is where that will be. The rear crosspiece is for structural rigidity and…oh wait! That’s an empty space! I could put more fuel in there! The thought is that the sponson tanks would be fuel cells. Since there is a float on an arm inside a gas (petrol) tank that enables the fuel gauge to work, I knew I was going to need a feed-tank for both fuel cells to feed into (which is where the fuel pumps would draw from) and that’s where the fuel sender assembly would go. The fuel gauge would always read “full” until both sponson tanks had emptied into the collection tank. Once the the fuel gauge began to move, it would be time to find a refueling place, the potential distance to which would be governed by the capacity of the collection tank and the distance this car could go on that amount of fuel:

Of course I’d glued (securely, of course) that second crosspiece in place before I realized that I could move it back and increase the fuel capacity, and therefore range, before the absence of go-juice turned the driver into an annoyed pedestrian. That will be taken care of!

And speaking of partition, it was time to get to work on that.

I HATE MATCHING AN INTERIOR CURVE. HATE IT HATE IT HATE IT. Yet match it I must. Ever see a contour gauge? That tool with all the movable wires that gets pressed across the face of a curve to be replicated? I have one. No. It doesn’t work all that well on something this small. But the idea of that gauge I could reproduce using strips of styrene. So I used .040″ (1.016mm) strips instead of wires. The body was placed over the monocoque and taped in place, then I placed one strip of plastic into the space between the two crosspieces and lightly glued it vertically at the base with the top (I thought) in contact with the roof. Subsequent strips were glued only to each other (I thought) in the same manner until I have a workable copy of the inside of the roof between the sponsons:

Yes…I see the space at the top of the center strip. Now. I didn’t then and just continued blithely on with it.

But I got it to work in spite of myself:

And then traced it onto .030″ (.762mm)” for rigidity:

And then the fitting happened…and happened…and happened… Finally my brain decided to join the party and I realized that I would be adding a strip of styrene on either side of this partition because in reality, I would need to attach this to the roof somehow:

Certainly good enough!

Now to add the wings using the same procedure with styrene strips, only using .015″ (.381mm) for ease of removal:

It ain’t pretty, but it worked. I added the wings of the same thickness as the center section of the partition:

Once fitted (and yes…it was as tedious as the last one was), I added structural support to the back and then laid out the rear window and cut the opening:

I learned my lesson with the M4 build as to how difficult it can be to fit clear styrene into an opening. I’m not doing that again. What I am doing is to using a sheet of .015″ (.381mm) clear and sandwich the clear between the part I just made and the one I’m about to make, also of .015″ (.381mm):

I placed the clear panel in place and then added .015″ (.381mm) around it for structure and to keep the clear panel from having any ability to move and then glued everything down:

Then it was time to join the front to the back and check fit:

Fits there…let’s see if the Eyecrometer got the window opening correct relative to the body:

Yep! Just where I wanted it.

Crankenstein – 1/25 Scale Kitbash Build #1 Parts Layout and Resin Casting

This project has been rattling around under my wig (not that I wear one) since I rekindled my model-building fire in ’14. I’m going to stuff a Small Block Chevy (SBC) into a Karmann-Ghia where the rear seat would go if it had one. (I’d always rather stuff too large an engine into a car than a back seat.) Nobody makes a kit of this…configuration…which means there will be much kit-bashing and scratch-building and whining complaints. (Hopefully it will also be entertaining.) It’s my intention to clam-shell the rear body from the doors back (and possible the front body as well but I haven’t decided yet), rework the doors so that they’re “suicide doors,” which are doors that are hinged at the rear (because of how I’m planning on doing the roll-cage), plus fender flares. That’s the short list!

It starts with this:

At this point, the only parts I’m fairly certain I’ll be using from the kit are these (I’m not sure about some of the clear parts):

What will drive this build and determine where things go will be where the engine goes and how much room that allows. I want to play automotive engineer as little as possible because I’m not an automotive engineer. That means I’m planning on raiding kits that I have in the stash. A small, light, over-powered car…hmm…where have I heard about this before? Oh! The Ford GT40! It so happens that I have two IMC GT40s, the MkI (#104-200) and the MkII (#112-200) on hand. Those were really good kits back in the mid 60s (Adam’s navel, that was FIFTY YEARS AGO!) but half a century ago [INSERT WHINING HERE] the standards of accuracy were so much lower. I took the engine/transaxle parts from the MkI kit, glued enough of the parts together to learn if I have enough room to do this (looks like it, sorta) and that the transaxle supplied with this kit is utterly inaccurate.

I went online to see if anyone made a 1/24-1/25 scale ZF transaxle and I found naught. Okay…I’ll scratch-build one. To see if the transaxle from the MkII kit was any better, I opened the box and was pleasantly surprised. No, the transaxle in the MkII wasn’t any better (it looked identical to the MkI), I had gone online to see if I could find any AM goodies for it back when I’d purchased it a few years ago and I did. Historic Racing Miniatures made what looked like a nice resin AM set. Excellent! I’ll just cut the ZF off the 7L engine and…whoa. Wait a sec. I decided that before I sacrificed this part, because I do have those two kits I’d hoped to use this in, let’s see if I can replace the part that I’m about to butcher. Good thing I looked because it seems that HRM closed its doors shortly after my purchase. Bugger. That means it’s mold making time.

Since both my molding rubber and casting resin have been sitting around for at least a couple of years, perhaps even to the pre-Covid period, they’re certainly past their use-by date. So I ordered more.

I’ve seen resin SBCs online but for some reason I decided that I didn’t want to do a resin engine (I have no actual reason for that decision, so chalk one more notion up to mood and whimsy), so I checked online and FB modeling groups to see if there was a kit that offered a nice rendition of the SBC in plastic. The consensus from a couple of online locations is that Revell’s ’69 Chevy Nova SS (kit #85-2098) is pretty good. Got my hands on one and I support the consensus. It’s pretty good.

So look…I get that I’m a bit off center (amazing what one can learn about oneself in SIXTY YEARS). For whatever “reason” (because mood and whimsy ain’t always “reason”) (in fact, they’re rarely “reason”), I decided that since I’m going to be making molds anyway, I’ll go ahead and take a mold of the SBC and cast one in resin! I’d bought another kit for its engine because I didn’t want to use a resin AM part, but I’m going to use a resin copy of the kit’s part instead? The irony isn’t lost on me (unlike my sanity, evidently, or consistency). In order to mold the SBC parts I’m going to need to do some assembly and cut the 4-speed transmission free (the nicest replication of a Muncie 4-speed I’ve yet seen) and then block off the holes left in the engine and trans (I’ve also attached the intake manifold) so that they don’t fill with rubber when I pour it:

I wanted to make the mold with the heads and valve covers attached to the block along with the spin-on oil filter. Fitting the heads to the block shows an unacceptable gap between the heads and manifold so I shimmed the gaps with .005″ (.127mm) and .010″ (.254mm) scrap styrene:

Since I’m going to change to suicide doors, I needed to decide how. It will be much easier to move the hinges from the front to the rear if the rear of the doors are vertical instead of curved and angled. And since there are going to be lots of bits stuffed into a volumetrically-challenged interior, I need to figure out where the fuel tanks will go. At this point I realized that I need some idea of what I have to work with. I tacked the major interior parts together so that I could check how much space, and where that space is, to work with:

My intent is to have a minimum of 20 gallons (just under 76 liters) of fuel onboard. I haven’t taken exact measurements yet but if I take another notion from the GT40 and put the fuel tanks in the door sills, that could give me the total fuel quantity I want. And if I move the door sills up just a little, that would work to help the chassis by adding rigidity as well as increasing fuel quantity. I’m going to open the doors at the bottom between the two chrome strips. I’m also going to need an air intake for the carburetor (no fuel injection…I’m doing this using early/mid 70s tech) so I added .020″ (.508mm) scrap styrene to blank out the left side rear window which is where the air intake will go. I puttied the panel lines I won’t be using and penciled in a rough approximation of where I want the doors to hinge:

I added the heads to the SBC and trimmed back the shims and realized that, once again, kit manufacturers seem to replace what should have an aluminum finish with chrome (more irony since the “chrome” added to car kits isn’t chrome, it’s aluminum). In the case of this SBC, that means the valve covers, fuel pump, and air cleaner housing (which I think I’m going to replace with an AM assembly) are chrome…which I don’t want. I’ve noticed that when builders want to strip chrome, they use some pretty caustic stuff; oven cleaner, brake fluid, and several types of paint strippers. Well, if it works for them… I’ve found that simple household bleach works great. It’s cheap (so that I can spend my cost savings on more AM goodies) and I can just flush down the drain without ecological penalty after using it. I think the longest it took me to strip chrome was from the Bugatti Type 35B I built. Half an hour. These parts were stripped to bare plastic in 15 minutes:

I’m not building a show car or custom anything (well, aside from most of the build, that is). This isn’t intended to be a trailer-queen and I’m building it as the street racer I wanted when I was young and more enthusiastic than smart. And if I had built this Back Then, I wouldn’t bother with dress-up parts; stamped metal is just fine. I’ll be painting these the standard color that Chevy used.

I wanted to get a rough idea about how well (nor not) this thing will fit into what limited space there seems to be and it looks like it’s going to be snug. I’m prepared (grudgingly) to move the rear wheel wells rearward if I need to:

As you can see in the above photo, I added some bolts to the engine that it needed as well as what will be the pouring block when it’s molded.

Since I was still awaiting the molding materials, I figured it was high time to get the parts ready to mold:

When doing the GT40 suspension upgrade parts, I realized that molding a coil-over part would be tedious, if even possible, so I just scratch-built a pair. My first attempt used a plastic rod with annealed copper wire wrapped around it for the spring:

Freakin’ tedious for marginal results. Instead, I used annealed 22 gauge copper wire twisted around a screw. It was easy to maintain even gaps between the coils and the gaps between the coils were easily adjusted. I will do the coil-overs for the front suspension later using thinner wire. On the two rear coil-overs, I left one end flat; I’ll figure out later what sort of attachment I’ll need there:

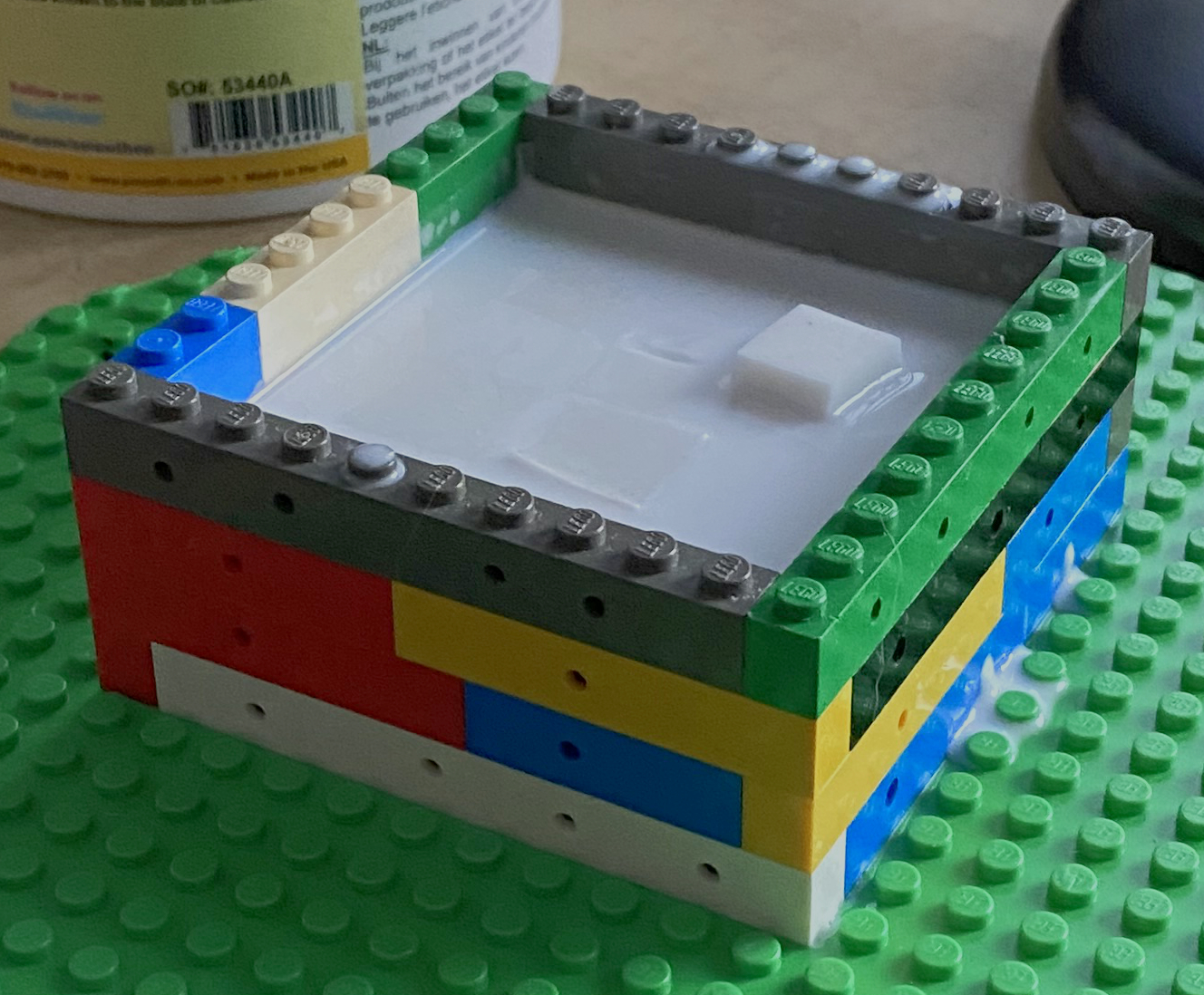

With the molding supplies in hand, I started making mold boxes and going through that process. Once again perfection eludes me. I thought that all I’d need was 150g of rubber. Nope. Events showed me that I should have mixed up (and boy am I often mixed up) 200g. 150g just barely covered the SBC block. I’m being giddy using the word “covered.” Had it cured at the thickness as poured, the “covered” area would be more of a membrane and therefore easily ripped. I scraped all the rubber out of the mixing container that I could to get that inadequate coverage. Then I remembered seeing someone who had cut the cured rubber left over from other molds and I filled out the volume of the mold box a bit and by dropping the cured rubber chunks into the uncured rubber, being certain that I got enough support over the engine part by dropping a block of cured rubber directly over it:

Once that had cured, I laid out an estimation of how I wanted to mold the HRM parts that I want to use in this build:

While that rubber-filled box was curing (without repeating my previous error of not enough rubber mixed), I laid out the IMC parts in its own box (these parts have also been dechromed):

Molds are done:

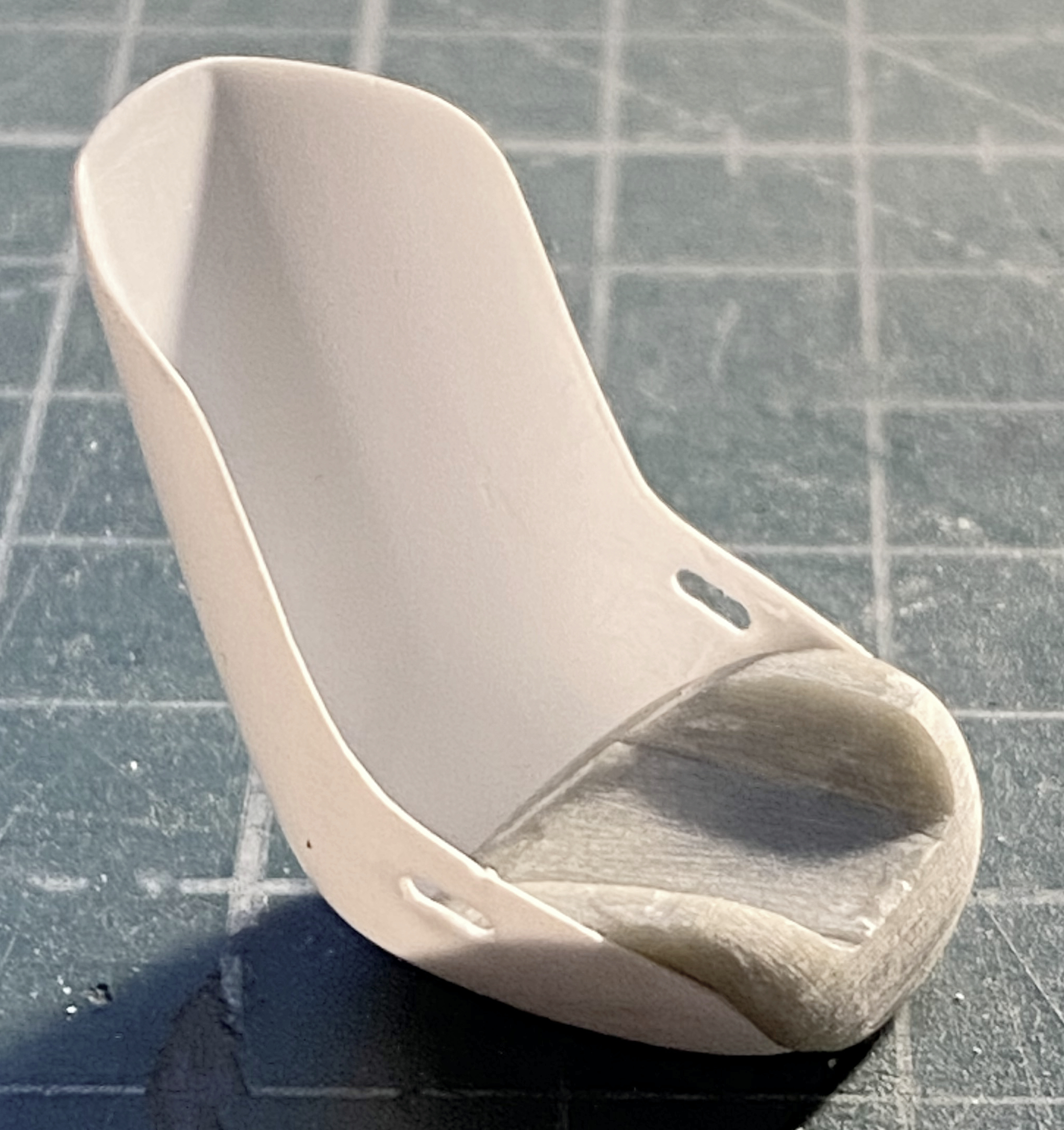

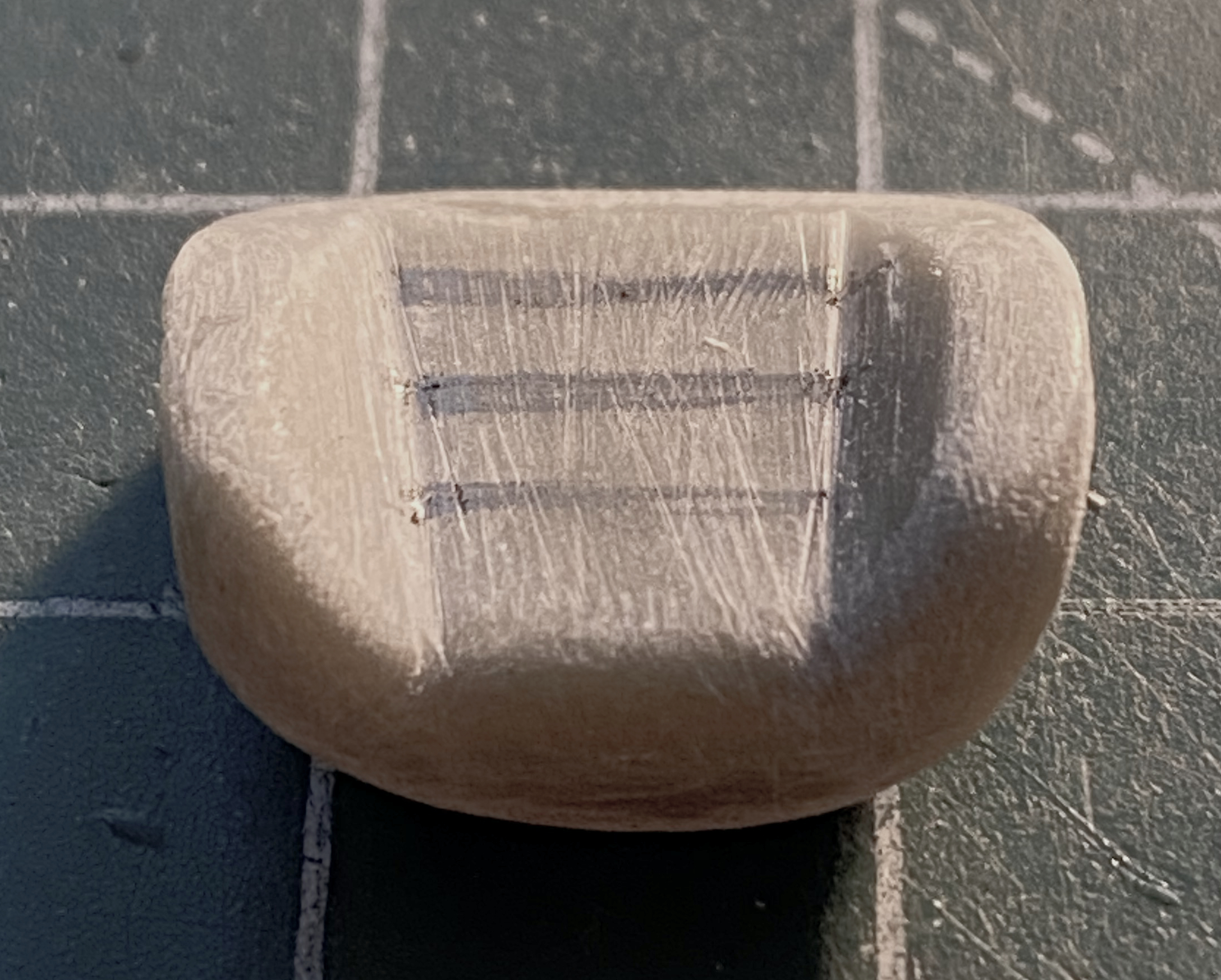

The next thing I tried was to make a custom bucket seat for the driver. I’ve seen a lot of resin seats online but they’re all modern or intended for drag racing. Why can’t I used a drag racing seat? Road racing cars are subjected to lateral G-loading more often than drag racing seats because unless something really goes wrong, that seat won’t have to deal with lateral loading as much as a road racing seat. I started with Aves Apoxie Sculpt:

It cures into something pretty hard, yet it’s easy to cut and shape. I started with a block that I intended to form into a buck that I could vacuform the body of the seat over (the rubber mold it’s resting against is to keep one end of it bent up until it hardens):

After sawing, filing, sanding, (and bitching at another one of my “clever” ideas) I ended up with a shape I thought would work. The buck was mounted on a scrap piece of styrene tubing and then it was glued to the platen of a vacuum-molder:

Normally I use .010″ (254mm) up to .020″ (.508mm) for vacuforming, but plastic stretches quite a bit when it’s vacuformed, meaning I would end up with something far too thin for scale. This time I used .030″ (.762mm) and this is what I ended up with:

The folds to the right of the photo going from the platen to the buck are significantly thicker than I’d expected. I’m not sure why it happened like this but my suspicion is that the thicker plastic combined with the significant suction of this molder (an old dental molder) may have been responsible. But because the plastic is thicker than what I normally use, I wondered if I could fix that. I mean…I still have the buck so the only thing at risk was a sheet of styrene. Once I had cut away the excess plastic, I applied a liberal quantity of Tamiya Extra-thin inside and out, and clamped the outside of the “fins” tightly. After letting it sit overnight, I cut, filed, and sanded the fins away. Though it almost worked, the last bit on the inside of those “fins” didn’t bond. It was so close that I used a couple of strips of scrap .005″ (.127mm) styrene as reinforcements inside the bucket, figuring that the seat cushion will hide the addition, and filled the gap with 3M Acrylic Putty. I think it worked well. At the bottom left corner you can see where the fold was:

A closer shot of the other side:

And if you look closely at the above photo you can see an oval penciled onto the plastic. This is the cutout for where the lap belt will go through. To keep the unsupported plastic from deforming under the drawing and drilling steps, I placed it back onto the buck for support (and this photo clearly shows the strips I’d glued to the inside of the bucket to support the fix of the sides):

Using more Apoxie Sculpt, I formed the raw blanks for the seat cushions. This epoxy putty will adhere to whatever it rests on/against while it hardens. Rather than try to make a more generic form, I wanted these cushions to fit snugly to the bare seat (for what I hope are obvious reasons), but I knew that if I just stuffed the plastic seat with the putty, I’d probably destroy the seat getting the cured putty to release from it so I could shape them. So I wrapped the seat in plastic wrap before stuffing the putty into place(s):

I came back the next day, peeled the plastic film off, and checked the fit of the blanks. Just right:

Then the sculpting process (which isn’t finished yet) was started on the bottom seat cushion, initially using a Dremel, and then graduating to files and sandpaper:

With all the molds made, I mixed up a batch of resin, added just enough dye (formulated for this purpose) to make the parts gray (or grey) and make it easier for my old eyes to see, and poured resin. Most of the parts came out quite well, with a couple of exceptions. The large part above the ZF transaxle is the suspension mount subframe. One of the lower arms snapped while I was prying it out of the mold (you can see the resultant crack at the bottom right, just above the pouring block…no problem to glue back together). The other problem was the oil pan for the SBC. With the first pour I didn’t add enough resin to fill it and the flange where it mates with the block didn’t fill. Essentially an open-back mold, I filled it with resin again and, figuring that there really wasn’t any place for bubbles to form, I didn’t put it under pressure. It was late and I didn’t want the compressor in the garage cycling on and off as pressure leaked out, so I just let it sit overnight on the bench. Mistake. The resin, being exothermic, produces gas as it cures. With it under pressure, the gas bubbles are compressed into invisibility (where they form at all). That doesn’t happen if some beef-wit lets it sit on his work bench overnight…and every place there’s supposed to be a bolt head on the mounting flange is also a bubble:

So I tried it again and poured another one, except this time under pressure. Well…as it turns out, my garage, being unheated and where the compressor is, didn’t really allow enough heat energy for the resin to cure within the four-hour elapsed time it’s supposed to cure. When I took the mold out of the pressure pot, I saw that the resin was about the consistency of grape jelly. I figured that since there wasn’t enough heat energy in the garage, I’d stick it in the oven for a half hour at 170F (76.66C). I was only half successful. The resin continued to cure, but since it wasn’t under pressure…well…let’s just call that a “learning experience.” The next day, I mixed more resin, stuck it into the pressure pot at 60psi, and instead of letting it cure for four hours, because it’s still cold in the garage, I let it stay out there for nine hours. By this time it was getting a bit late and I still didn’t want the compressor to cycle all night. I closed the valve on the pressure pot but disconnected it from the compressor (which was shut down and drained). Without releasing the pressure (which still indicated 60psi on the gauge), I brought the pressure pot into the (comfortably warm) shop and let it sit for another three hours while the pressure bled off. After that three hours the pressure had dropped to a little over 20psi. I opened the valve, took the molds out, and demolded the oil pan. Success! A nice, dense, bubble-free, casting that I can use.

I’m interested to see what other “learning experiences” the next month will teach me.

Crankenstein – A Brief Overview

This is an unusual Overview in that the object I’m discussing never (to my limited knowledge) existed…and this starts with Kelmark Engineering.